Thunder in the Morning Calm (38 page)

Read Thunder in the Morning Calm Online

Authors: Don Brown

“Nothing we can do,” Frank said. “Go back to sleep. Hope they don’t come this way.”

“I don’t care if they do come,” Keith said. “If they want to shoot me, let ‘em.”

“Don’t give up, old friend. I know you and Robert were close. It’s just the two of us now. We’ve got to stick together. There is always hope.”

“Hope lived once upon a time,” Keith said. “Hope died with Robert.”

Office of Colonel Song Kwang-sun

D

o you hear that, Colonel?” Jung-Hoon puffed on the cigarette, holding it with his left hand, and kept the pistol aimed at Song’s head with his right. “Hear that gunfire? Know what that is? Let me give you a hint. That gunfire is not from Russian-made AK-47s. It is from American-made M-16s. And at this very moment, your secret empire of oppression is crumbling in the falling snow.”

“You will never get away with this,” Song snarled.

“No?” Jung-Hoon said. “Maybe. Maybe not. But you will not be alive to find out. Now then, I believe I asked you a question. Has to do with whether you have ever had your neck scorched by a burning cigarette.”

Song defiantly turned his head away, still refusing to answer.

“Pak, while the good colonel decides if he would like to feel the burning end of a cigarette on his neck, tie up our pretty little red-dressed flower. Tie her legs and feet to the legs of the colonel’s big fat desk. I have only a limited supply of ammunition to waste tonight.”

“Yes, Jung-Hoon.”

That brought a raised eyebrow from Colonel Song. “Who

are

you?”

“I am Colonel Jung-Hoon, Army of the Republic of Korea.”

“Jung-Hoon.” A bewildered look of recognition came across Colonel Song’s face. “I have heard of you. I thought you were retired.”

Jung-Hoon drew a final drag from the cigarette, then smashed it out on Song’s desk. “Colonel, I shall never retire from my hatred of

socialism, or communism, or tyrants who seek to control others, taxing them to death and stealing their property. Nor shall I retire from my life’s conviction to see my nation, my Korea, reunified and rid forever of the swine Communist dictator in Pyongyang. But you, my friend, you are about to retire. Permanently! Look on the bright side. I am not going to torture you with a cigarette like you did to this nice lady.” He looked at Pak. “You have her tied down?”

“Yes, very tight.”

“Good. Go into the outer office and wait.”

“Yes, Jung-Hoon.”

He waited until she left and had closed the door. “I hope your service to the dictator was worth it.”

“What do you mean?” Song demanded.

Jung-Hoon pointed the .45 at Song’s head. “Your gun is on your desk, Colonel Song. You have two choices, it would seem. You can either get down on your knees before me, and I will have Pak come back in here and gag you and tie you down beside your mistress, or, if you want to be a real hero, you can always try to reach for that gun of yours.”

Song glared at him, his black eyes ablaze with anger.

“If I were you, Colonel Song, I’m not so sure I would take my chances with the gun. That blood dripping from your hand is proof that South Korean special forces are vastly superior marksmen than North Korean swine. Seems your poor marksmanship could be a hazard to your health. The much safer alternative would be for you to get on your knees and take the rope. That way you could live to explain to Dear Leader how you lost control of your camp while your attention was distracted by this woman.”

“How dare you try and humiliate me!”

“Humiliate you?” Jung-Hoon said. “I am in fact giving you a chance to save your life. Unless, of course, you think you are a quick enough draw to grab that gun off your desk and shoot me before I shoot you.”

Jung-Hoon smiled. He felt a brief moment of smug satisfaction as Song glared at him. Time froze. This was a stare-down for the ages, between North and South, between oppression and freedom. It was between mortal enemies — warrior colonels — one trained to kill in defense of freedom, the other trained to kill to further the evils of totalitarianism.

“My dear Colonel Song,” Jung-Hoon said, “they do teach you to use your brains here in the Democratic People’s Republic, do they not? To think? I would suggest you use your brain and get down on your knees so that I do not have to blow your brains out.”

Song did not blink. In a quick, jerking movement, his bleeding hand reached across the desk for his gun.

Blam!

The colonel was thrown back, away from the desk, landing sprawled on the floor against the wall. His assistant whimpered on the floor, certain she would be next.

Jung-Hoon checked both, then walked into the outer office. “He will never harm you again, Pak. Let’s go find the commander and Jackrabbit and get the old men out of here.”

Prisoners’ barracks

F

rank, someone’s at the door.” Keith pushed himself up from his bunk, his eyes on the locked door, which could only be unlocked from the outside.

“You’re right,” Frank said. “Somebody is jiggling the lock on the door.”

“Oh, I don’t like the sound of this.”

A booming explosion rocked the building. The door flew open. Snow swirled in on a blast of cold air.

Then a figure appeared in the doorway. A woman. She walked into the barracks and turned on the lights.

“Pak!” Keith exclaimed. “Are you all right?”

“I am fine, and now so are you,” Pak said. “There is someone here who wants to speak to you.”

“To us?”

She nodded.

The two men who walked into the barracks were all in black. Their faces were covered with black grease. Over their shoulders, they each carried a black assault rifle. They were stiff in their bearing, a formal military bearing.

Keith and Frank just stared up at them, their mouths open.

The one on the left stood a bit straighter, with shoulders back, eyes forward, and said, in a voice of confidence, “Gentlemen, we are Americans. We’ve come to take you home.”

On the road between Youngwang and Changjin

T

he clock showed ten at night. They had been driving along the dark, winding road about an hour. They had seen only two cars. Both were going in the opposite direction. There was no sign of police or the military. There was not much at all along the road. Just ahead lay the town of Changjin, where they would cut northwest across the mountainous heart of the country on the road that would lead them to the Yalu River and the Chinese border.

The phenomenal thunder-and-lightning snowstorm flashed in the sky behind them. Snowfall had lessened, and the road was passable. The two men they had plucked from the camp sat on the floor of the van, opposite Gunner, their legs covered by a blanket. Pak sat between them. She had one arm around each of their shoulders. She had been sobbing when they left the camp. Gunner wasn’t sure why and wasn’t about to ask.

“Here is our turn,” Jung-Hoon said. “About eighty miles to go.”

The van swung to the left, onto a different road. “Be ready for curves and mountains ahead,” Jung-Hoon said.

Pak and the two old men seemed like an odd, out-of-place family. Their faces were barely visible in the dark interior of the van, their expressions difficult to make out. Pak had been crying off and on, but said nothing. All Gunner knew about the men was their names — Keith and Frank. All three, the old men and Pak, seemed to be in a trance or perhaps were too overcome with emotion to talk.

Gunner had pictured this moment another way. He thought they

would be jubilant, talkative, utterly elated to be free. But then, when he thought of what it must have been like to be in brutal captivity for sixty years and then to be suddenly popped out of the cage in which you had been confined — he realized that he knew nothing about what they must be feeling. And, on top of that, sensing the danger that still faced them. No wonder they were speechless.

Against his natural instinct as an intelligence officer to ask question after question, Gunner decided to postpone any questions. His focus had to remain on getting them all out of North Korea, getting them all home safely. And he knew the danger they still faced.

There was one question that Gunner did not yet want to know the answer to. He could not ask about Robert. The pain, the disappointment, were too great.

Pak had warned Gunner, back at the psychiatric hospital, that Keith was very close to Robert, like a brother, and that he would be very upset because of Robert’s death. This news gave Gunner a sick-to-the-stomach feeling. His grandfather’s name was “Robert.” What if his grandfather had died only hours before they arrived? He couldn’t dwell on that possibility. Not now. Their mission — his mission — needed every man to remain sharp, alert. The safety of all depended on it.

He had stood at Robert’s grave in that frozen and forsaken prison camp. Not knowing. Robert was, after all, a common name. He imagined his grandfather in heaven, looking down and smiling, as his grandson sped north in a plumber’s van with the last two prisoners from a forgotten war fought some sixty years ago. That thought brought a smile to Gunner’s face.

The intel officer in him allowed him to ask one question: “Are you gentlemen hungry? We’ve got a bunch of MREs that we haven’t opened.”

No answer. Finally, Keith said, “No. No, thank you. Not hungry.”

“Okay,” Gunner said. “Could be a long night. Might be a good idea to try and get some sleep.”

Road that runs along the Yalu River

A

t two in the morning, Jung-Hoon woke up the others. “According to GPS, only two more miles to debarkation point,” he said, his eyes

searching for Gunner in the rearview mirror. “We should start getting our friends ready.”

“Get our rifles ready too,” Jackrabbit said. “Got that, Commander? M-16 and night scope. This area is crawling with border guards.”

“Rifle and pistol both good to go, Jackrabbit,” Gunner said.

The lights from the instrument panel on the dashboard of the van cast a dim glow into the back. Both Keith and Frank appeared to be snoozing, their heads resting on Pak’s shoulders. Pak, with her head cocked back and her mouth open and aimed at the van’s ceiling, was asleep between them. “Pak. Keith. Frank.” Gunner reached over and shook Keith’s knee.

“Aaahhh.” Keith opened his eyes.

“Sorry. Didn’t mean to hurt you. Time to get up. You too, Frank. We’re getting ready to cross the river into China. We’re going to walk across.” He felt the van slow down, then swing right.

“This is the road along the river,” Jung-Hoon said. “The Yalu or Amnok River Road. Our destination is one mile northeast of here.”

Gunner said, “The river is frozen and will be slippery. So watch your step. We’re all going to walk across. Jung-Hoon, could you hit the country map on the GPS so I can show where we are?”

“Sure.” Jung-Hoon punched the Back button a couple of times and the national map came up.

“Could you pass it back for a second?”

Jung-Hoon handed the GPS back to Gunner.

“This is called a GPS. Think of it as an ultrasophisticated radar and map. It can show us where we are at any place on the earth at any time.”

In the glow from the GPS screen, he could see their faces light up with interest.

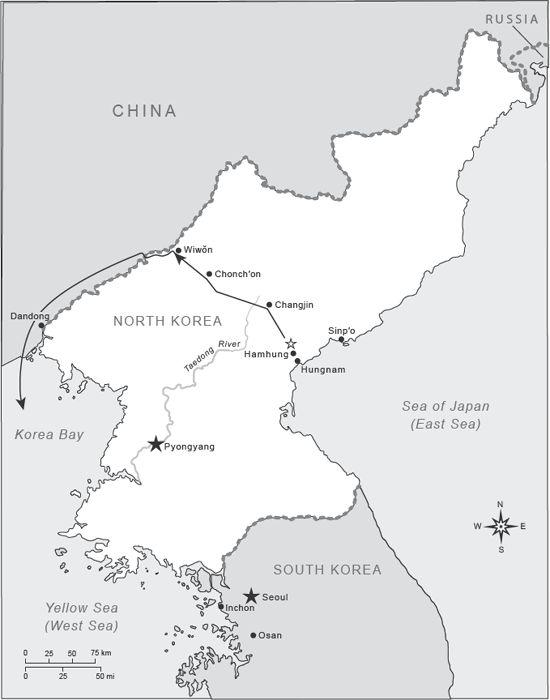

“Right now, we’re almost at the tip of this arrow, just outside the town of Wiwon. We just turned on the road that snakes alongside the river.

“We’re going to drive down here a little ways, and then we’ll ditch the van and cross the river. When we get to the other side, there are Christian missionaries who will meet us. They have a seaplane waiting for us. They’ll drive southwest on the Chinese side of the river all the way down to Dandong to the plane. We’ll take off for Inchon at sunrise.

Closeup of escape route, road along river,

prison to Wiwon to Dandong, Korea Bay

“From there we’ll take you to Osan Air Base, south of Seoul. We’re going to get you home.” Gunner gave the GPS back to Jung-Hoon.

“There are border guards in this area, so remain silent. We need to be careful.”

“Okay,” the old men said in unison.

“Here are jackets for you. It’s even colder here than it was back at the prison.”

A few minutes later, the GPS stated, “Destination is one mile on your right.”

“We are looking for a large stone on the right side of the road as the landmark,” Jung-Hoon said.

They rolled on for another two minutes.

Jackrabbit pointed over to the side of the road. “There’s our rock.”

“Okay, I’ll pull over to the right,” Jung-Hoon said. “I’ll park the van in front of the rock to block visibility from the rear at least. Then we unload and go.”

“Need to move fast,” Jackrabbit said. “China, here we come.”

DPRK patrol jeep

Amnok River Road

H

e had ten kills notched on his gunbelt. Ten times traitors had fallen from a bullet shot from his rifle. Five times he had been decorated in Pyongyang for his heroism in stopping escapes.