Thyroid for Dummies (8 page)

Read Thyroid for Dummies Online

Authors: Alan L. Rubin

much thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) or high

of TSH in the blood does not seem to impact

levels of thyroid autoantibodies, both of which

depression either.

are explained in Chapter 3. Could these other

Current research indicates that the level of the

chemical changes promote depression in some

thyroid hormones themselves affect mood, and

patients?

the levels of these other substances do not.

To date, scientists have found no correlation

between levels of these other chemical

06_031727 ch02.qxp 9/6/06 10:47 PM Page 24

24

Part I: Understanding the Thyroid

07_031727 ch03.qxp 9/6/06 10:45 PM Page 25

Chapter 3

Discovering How Your

Thyroid Works

In This Chapter

ᮣ Finding your thyroid

ᮣ Understanding how thyroid hormones are produced

ᮣ Carrying thyroid hormones around your body

ᮣ Seeing what thyroid hormones do

ᮣ Knowing when your thyroid is playing up

Your thyroid is a unique gland whose activity affects every part of your body. The gland makes

hormones

and sends them out into the bloodstream, which carries them to every cell and organ.

Hormones are substances produced by a gland or tissue and transported by the blood to act on a remote organ or tissue, where they produce an effect.

These hormones perform many different functions depending upon the particular organ that responds to them.

This chapter shows you how to locate your thyroid. If you have really sensitive fingertips, and your thyroid is slightly on the large side, you might even manage to feel it – in fact, it’s often easily findable in normal women. I also cover in this chapter the names of the various hormones that control the thyroid, and those that the thyroid produces itself, before looking at what thyroid hormones do to help your various internal organs work more efficiently.

This chapter also shows you how to recognise when your thyroid is abnormal in size and shape and what happens to your body when thyroid hormones are produced in quantities that are too large or too small.

By reading this whole chapter, you’ll know so much about thyroid function that you’ll never suffer from undiagnosed

hamburger hyperthyroidism

, a real disease that results from eating cuts of meat that include the thyroid gland of the cow. Eeeugh.

07_031727 ch03.qxp 9/6/06 10:45 PM Page 26

26

Part I: Understanding the Thyroid

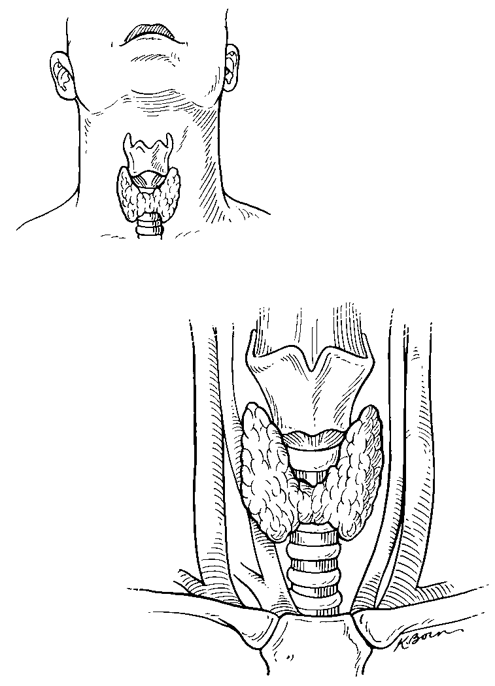

Locating the Thyroid

Have you ever seen one of those wonderful anatomy books where you peel the layers away, starting with the skin, to see all the inner structures of the body? If you do that with the neck, as soon as you peel away the skin you find a bony, V-shaped notch created by the connection of the inside edges of the collar bones. Basically, the main tissue that surrounds the front and sides of the trachea (windpipe) between this V and your Adam’s apple is the thyroid gland. The thyroid is shown in Figure 3-1 with some of the more important surrounding structures.

If you want to find your own thyroid (without peeling away your skin), place your index finger at that bony notch below your Adam’s apple and push your finger toward the back of your neck. If you then swallow, you may feel something push up against your finger. That is your thyroid gland.

As you can see in Figure 3-1, the thyroid is shaped a bit like a butterfly (or possibly more like upside-down angel’s wings). The wings of the butterfly are called the left and right lobes of the thyroid. Connecting the lobes is the isthmus, a narrow strip of tissue between the two larger parts. A third thyroid lobe called the pyramidal lobe, which is another narrow strip of thyroid tissue rising up from the isthmus, is also sometimes visible.

Right

Left

Left common

Thyroid cartilage

carotid artery

Thyroid gland

Left jugular vein

Figure 3-1:

The thyroid

Trachea

Clavicle

gland and

(windpipe)

surrounding

anatomy.

07_031727 ch03.qxp 9/6/06 10:45 PM Page 27

Chapter 3: Discovering How Your Thyroid Works

27

When the thyroid is normal in size, it weighs between 10 and 20 grams. That equates to between one-fiftieth and one-twenty-fifth of a pound – not terribly large considering everything it does. Each lobe of the thyroid is only about the size of your thumb. Even so, the thyroid is one of the largest hormone-producing glands in your body.

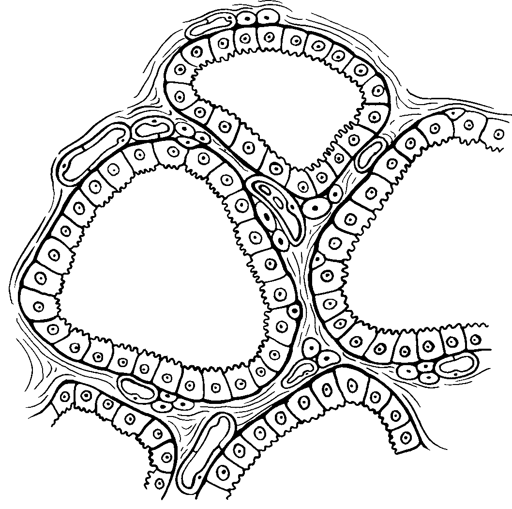

When looking at the thyroid under a microscope, you can see that it consists of rings of cells one layer deep with a clear centre that acts as a storage depot for the thyroid hormones. These rings are called follicles and are shown in Figure 3-2.

In a developing embryo, the thyroid starts life at the base of the tongue. It then descends to the middle of the neck. In some people, remnants of thyroid still exist at the base of the tongue (known as a lingual thyroid) or along the line of descent.

Blood capillary

Parafollicular (c) cell

Epithelium of follicle

Lymphatic vessel

Follicular cell

Basement

membrane

Connective tissue

Figure 3-2:

A micro-

scopic

view of the

thyroid

gland.

Colloid containing

thyroid hormones

07_031727 ch03.qxp 9/6/06 10:45 PM Page 28

28

Part I: Understanding the Thyroid

Producing Thyroid Hormones

The production of thyroid hormones is regulated by master hormones produced in the brain, as shown in Figure 3-3.

T4 + T3

HYPOTHALAMUS

T4 → T3

TRH (+)

T4 → T3

PITUITARY

T4 + T3

TSH (+)

Figure 3-3:

Thyroid

THYROID

hormone

production.

A part of the brain known as the

hypothalamus

produces a hormone called

thyrotrophin-releasing hormone (TRH)

. This hormone is carried a short distance in the brain to the pituitary gland, where it promotes the release of

thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

.

TSH leaves the pituitary gland and travels in the bloodstream to your thyroid, where it causes the production and release of two thyroid hormones:

thyroxine (T4)

and

triiodothyronine

, which, as they’re a bit of a mouthful, are normally known as

T3

. (The numbers 3 and 4 refer to the number of atoms of iodine in the hormones.)

ߜ T3 is the active form of thyroid hormone.

ߜ T4 is considered a

prohormone

(literally meaning a ‘before hormone’), a much weaker chemical that gains its potency only after being converted to T3.

The conversion of T4 to T3 takes place in many parts of the body (wherever thyroid hormones do their work), not just in the thyroid. The thyroid gland 07_031727 ch03.qxp 9/6/06 10:45 PM Page 29

Chapter 3: Discovering How Your Thyroid Works

29

normally releases about 13 times as much T4 as T3. However, overall, you only produce about three times as much T4 as T3. This deficit occurs because most of your T4 is converted into T3 in organs such as the liver, kidneys, and muscles. The thyroid gland itself releases only 20 per cent of the T3 you produce every day.

The statement in the preceding paragraph is profoundly important when treating thyroid hormone deficiencies. Most people with hypothyroidism (low thyroid function) lack both T3 and T4, but during treatment – when taking daily doses of replacement thyroid hormone – they receive only T4.

Their bodies must get the T3 they need by converting the T4 into T3. Despite this conversion, these people are still somewhat deficient in T3. Chapter 5

discusses this problem and its possible solutions in more detail in the section

‘Taking the right hormones’.

Identifying the importance of iodine

Both T3 and T4 thyroid hormones contain iodine:

ߜ One molecule of thyroxine (T4) contains four atoms of iodine, which make up 65 per cent of its weight.

ߜ In contrast, one molecule of triiodothyronine (T3) contains three atoms of iodine, which makes up 58 per cent of its weight.

In fact, your thyroid gland contains the highest concentration of iodine in your body as the gland traps iodine to ensure that it has a ready supply to make its hormones. Because of this fact, the workings of the thyroid are easily studied if radioactive iodine is substituted for regular iodine. In a medical investigation called a

thyroid scan and uptake

, someone with a suspected thyroid problem takes a known dose of radioactive iodine, and the amount that ends up sticking to their thyroid is detected and measured with a refined version of a Geiger counter (see Chapter 4).

Other organs, such as the breasts, the stomach, and the salivary glands, also trap iodine. However, no other organ in your body except the thyroid gland uses iodine for any important purpose, and thyroid hormones are the only significant chemicals you possess that contain iodine.

Regulating thyroid hormones

When thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) from your pituitary reaches your thyroid, two things happen:

ߜ First, the TSH causes the release of existing thyroid hormone into the blood (similar to Blue Peter’s famous line of ‘Here’s one I made earlier’).

07_031727 ch03.qxp 9/6/06 10:45 PM Page 30

30

Part I: Understanding the Thyroid

ߜ Second, the TSH prompts the production of more thyroid hormones, both T3 and T4, which collect in the space inside the follicles, awaiting future release. (If your TSH levels are elevated, it can also stimulate overall growth of your thyroid, which can lead to an enlarged thyroid called a goitre.)

The released T3 and T4 circulate throughout your body, reaching, among other places, the pituitary gland. Your pituitary gland has special sensors that detect how much thyroid hormone is present. If the pituitary detects just the right amount, it continues to release the same amount of TSH. If thyroid hormone levels drop for any reason, the pituitary releases more TSH

to stimulate the thyroid and tell it to get a move on with making and releasing more thyroid hormone (if it can). However, if the pituitary detects excessive amounts of thyroid hormone, it cuts back on the amount of TSH it produces, so TSH levels fall. This to and fro dialogue between the thyroid and pituitary glands is called the negative feedback for TSH release.

In short, as thyroid hormone falls, TSH rises, and as thyroid hormone rises, TSH falls. Because T3, T4, and TSH are all easily measurable in a blood sample, it’s a relatively simple task for laboratory tests to determine the state of your thyroid function (see Chapter 4).

As TSH is also regulated by the release of thyrotrophin-releasing hormone (TRH) from the hypothalamus (see Figure 3-3), the level of TSH in your blood remains very stable throughout life, and abnormal levels usually mean some disease is present.

Moving thyroid hormones around

After T3 and T4 are released from the thyroid, they don’t just travel loosely in your blood to their targets – special proteins in the bloodstream carry them.

Because 99.97 per cent of thyroid hormone is attached to proteins, only 0.03

per cent floats freely in your circulation.

Only the free thyroid hormone can leave your blood and enter your cells. The rest is solidly bound to proteins and is not available to perform the actions of thyroid hormone – essentially, it’s inactive. When a doctor measures the total thyroid hormone in your blood, she measures bound hormone along with the unbound hormone. If she only knows the total T4 amount in your blood, she needs to order a second test to determine the unbound T4 – the hormone that is free in your blood. This second test is important because many drugs and diseases alter the blood levels of thyroxine-binding proteins – the proteins that thyroid hormones bind to. If a drug like oestrogen, for example, increases the amount of thyroxine-binding proteins in your body, your thyroid makes 07_031727 ch03.qxp 9/6/06 10:45 PM Page 31