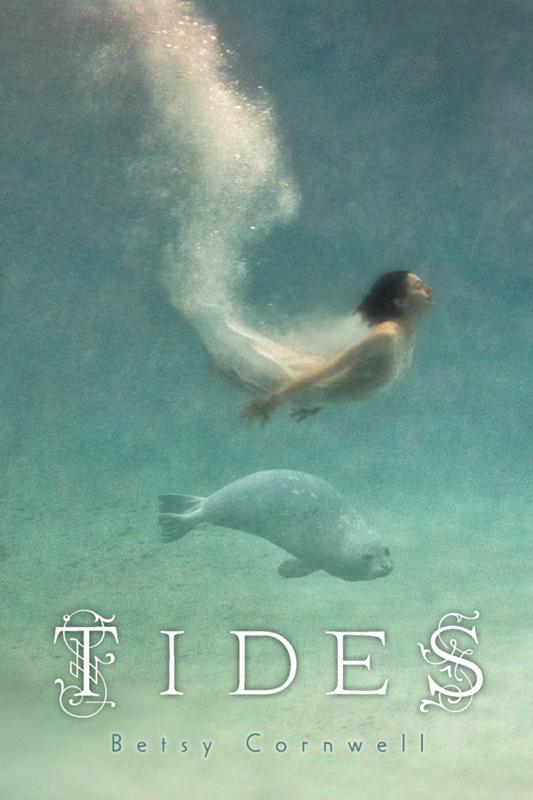

Tides

Authors: Betsy Cornwell

Clarion Books

215 Park Avenue South

New York, New York 10003

Copyright © 2013 by Betsy Cornwell

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Clarion Books is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Cornwell, Betsy.

Tides / by Betsy Cornwell.

pages cm

Summary: After moving to the Isles of Shoals for a marine biology internship, eighteen-year-old Noah learns of his grandmother’s romance with a selkie woman, falls for the selkie’s daughter, and must work with her to rescue her siblings from his mentor’s cruel experiments.

ISBN 978-0-547-92772-5 (hardcover)

[1. Selkies—Fiction. 2. Love—Fiction. 3. Internship programs—Fiction. 4. Isles of Shoals (Me. and N.H.)—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.C816457Ti 2013

[Fic]—dc23

2012022415

eISBN 978-0-547-92775-6

v1.0613

for Corey

The cure for everything is salt water: sweat, tears, or the sea.

—Isak Dinesen

i carry your heart (i carry it in my heart)

P—E. E. Cummings

ROLOGUE

T

HE

color at the bottom is so deep, there are few who would call it blue.

There is light there—a little—for those who can find it. It shifts in the water, a vague, New England light. Just darkness unless you look carefully. If you want real light, you’ll have to stay on the surface.

The Isles of Shoals have plenty of it, light that refracts off the salt-swept rocks and old whitewashed houses. Light that clinks its way over the waves like so much dropped and dented silverware.

It will hurt your eyes to look, on those bright summer days. You’ll sit on the rocks until the spray dries and strings salt beads in your hair, but the brightness will eventually hurt.

Be careful. That not-blue of the deepest water will call to you, a seeming balm for your stinging eyes. But it will surprise you.

It’s the shallow water you really want, what the Old Shoalers call the inbetween. It’s that space between light and blue, land and sea, where the water is sometimes warm. The little fish swim there.

Once you’re safe in the inbetween, you’ll wonder why you’d ever dare to broach the deep, with its hidden teeth and tentacles. You’ll reject the white sun and dry salt above. For a while.

It’s the colors that will make you stray. They sing to you, the not-blue and the searing light, and no matter how tightly you tie yourself to the inbetween, eventually you will break free.

No one swims only in the shallow water.

one

ALES

N

O

one is happy in the inbetween,” said Gemm. “Not even selkies.”

Wind moaned in at them through the windows. Gemm quieted, letting the weather have its interruption.

Her grandchildren stared at her, wide-eyed, mugs of tea growing cold in their hands. It didn’t occur to Noah that he was far too old for these stories.

Well, that wasn’t really true. The thought occurred to him—but in his father’s voice instead of his own, as too many of his thoughts tended to do.

Gotta stop that.

He glanced at his sister, Lo, seated next to him at Gemm’s kitchen table. She was still wrapped in the story, her face open with wonder. She pushed aside a black length of hair that had fallen over her eyes. Noah wondered if she felt too old for fairy tales, too. These days, Lo seemed to think she was too old for everything.

Noah tapped the side of his mug. He hadn’t come to the Isles of Shoals to listen to fairy tales. He had an internship at the Marine Science Research Center on nearby Appledore Island, and starting tomorrow he’d work long hours there until he left for college in August. If he did well, this internship would be his first real step toward becoming a marine biologist—something Noah had wanted since the first time his father took him fishing.

He remembered staring into the green water, watching a bluefish glint out of the murk and flash and fight as his father pulled it into the boat. The fish had been almost as big as five-year-old Noah, and he’d thought it was a monster, all metal-bright scales and spiked fins.

Noah loved that monster. He was desperate to know what else lurked and slept and waited in the water, and he knew he’d spend the rest of his life trying to find out.

That’s why I’m out here in the middle of nowhere this summer, anyway,

he thought

.

He was choosing this dream over every other consideration, something he’d done many times before—maybe too many times. Noah remembered all the nights he’d stayed up studying, all the dances he’d skipped, all the time he’d spent alone—so much that he didn’t even mind, really, being alone. He kind of preferred it.

He’d worked so hard just to get here. Starting tomorrow, he’d work even harder. He told himself he’d earned the chance to feel childish once in a while, to listen to a fairy tale without overanalyzing everything. He tried to slip back into the rhythm of Gemm’s story.

“The land calls to the selkies, sings to them, promises of new knowledge and new joy. It whispers to them, and they cannot avoid its call.” Gemm poured a thin stream of milk into her tea. Clouds bloomed in the dark liquid.

Noah closed his eyes and breathed in the ocean smell that filled his grandmother’s cottage. The beating, shuddering wind outside led him deeper into the tale.

“They swim to the rocks and the beaches, and they shed their seal forms. They look like people, then. Humans.”

The pale woman sitting beside Gemm—Maebh, she’d said her name was—took in a deep breath. The corner of her mouth twitched.

“Selkies need the land as we need the deep ocean,” said Gemm. “They need it for its danger and its mystery. They come to the beaches and they sing. They sing to the ocean and the sky.”

“Like sirens?” Lo asked. Noah knew she’d read the

Odyssey

in freshman English that year. He remembered reading it himself, but he preferred the part with Scylla and Charybdis, the two monsters on either side of your boat, with hardly any way to go between them.

“A bit like sirens,” Gemm said, smiling. “Their songs are very beautiful. But unlike sirens, selkies don’t mean you any harm with their songs. They don’t sing to seduce or to kill. Their songs have nothing to do with anyone but themselves. They sing for the simple joy of it, and because of that, I imagine their songs are more beautiful than those of any siren.”

Maebh and Lo both smiled at that.

Noah couldn’t help staring at Maebh for a moment. It wasn’t just that her skin was almost paler than white, as if she hadn’t seen sunlight in years. He thought she must be about thirty, but something about her—the way she moved?—seemed much older.

Maebh’s round dark eyes flicked toward his, and Noah lowered his gaze, embarrassed.

“In this story,” Gemm said meaningfully, as if she knew Noah hadn’t been paying attention, “there is a young fisher-man, the handsomest in his village. Many women noticed him, wanted him—even loved him. But he never loved any of them back. Some said his true love drowned when they were children. Others said he was simply too proud, thought himself too special for any of the village women.

“He enjoyed his life, his fishing, but he wasn’t satisfied. He often wandered the beaches at night, so handsome, but empty around the eyes. He brought a satchel with him to collect shells and sea glass and the like, but none of those things made him happy for long. He was looking for something—anything—that would satisfy him.”

Maebh stiffened in her chair. Her large round hands twisted together in her lap.

Gemm continued her story, unaware. “Once, just on the cusp of autumn, the young fisherman wandered on the beach very late into the night, and he heard something. It was a sort of music that trickled through the air, low and sweet and eerie. He started to run, rushing over the rocky shoreline, careening around boulders and tide pools, hunting the source of that beautiful sound.

“He tripped and fell onto a patch of sand. Blood trickled down a gash in his cheek, and his hands stung with scrapes. But the pain in his body was already fading away, borne out to sea by the wonderful songs he heard. He had found the source of the music.”

A slow, reluctant tear slipped down Maebh’s cheek.

Now Noah’s mother’s voice came into his head.

Your grandmother’s selfish, remember,

she’d whispered to him, just before she and his father had left the island that afternoon.

She’s always lost in her own world, and she’ll pay no attention to yours.

And then she had hugged him, just a little too tight, and walked out the door in her cloud of department store perfume.

Noah hadn’t really believed her. After all, Gemm had agreed to let Lo and him live with her for the summer—she couldn’t offer that much and be so very selfish. But now, seeing her rush on with a story that clearly upset her friend, Noah wondered. He watched Gemm while she spoke, willing her to look back at him.

“The music came from a group of people standing on the shore. They looked like no people the fisherman had ever seen—certainly no one from his village. A tall, elderly woman led the singing, and the others—there were perhaps two dozen—danced or waded in the surf or lounged on the rocks and sang to the moon that loomed above them, pale as their skin.

“It was one of these last that caught the fisherman’s eye. She sat on a boulder in the shallows, a small distance away from her companions. She was folded in on herself, resting her chin on her hands, and her hands on her knees. She sang in a clear, true alto that vibrated with some matching sound, some answering call, inside the fisherman himself.

“He realized he had forgotten to stand back up after his fall. He pushed himself quietly to his feet, hoping the singers wouldn’t notice him. But then he saw, down by his shoes, the thing that had tripped him. It wasn’t a rock, as he had assumed, but something soft, yielding under his touch. It glimmered a little in the moonlight, like velvet—though the fisherman was too poor to have ever seen real velvet.

“Once he held it in his hands, he recognized it: a sealskin, but larger and darker and finer than any the fisherman had seen before. He knew it must belong to a selkie. In that moment he knew who the singers were, and he knew what he must do.”

Maebh covered her mouth, but they all heard her choked sob.

Gemm stood and took Maebh’s hands in hers. She crouched down before her, so that their eyes were level. For a moment, they simply looked at each other. Then Gemm gently touched her hands to Maebh’s cheeks and brought their foreheads together—a gesture so intimate, it made Noah look away.