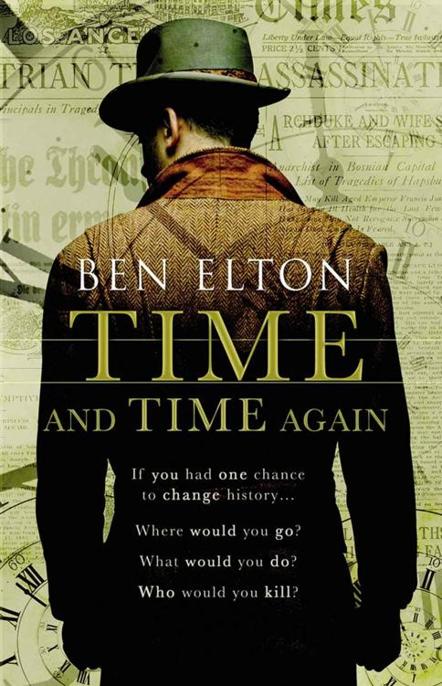

Time and Time Again

It’s the first of June 1914 and Hugh Stanton, ex-soldier and celebrated adventurer, is the loneliest man on earth. No one he has ever known or loved has been born yet. Perhaps now they never will be.

Stanton knows that a great and terrible war is coming. A collective suicidal madness that will destroy European civilization and bring misery to millions in the century to come. He knows this because, for him, that century is already history.

Somehow he must change that history. He must prevent the war. A war that will begin with a single bullet. But can a single bullet truly corrupt an entire century?

And, if so, could another single bullet save it?

Contents

Ben Elton

To History teachers.

History was my favourite subject at school – and has been ever since

In 1687 Sir Isaac Newton published his

Principia

, a work generally acknowledged to be the most influential publication in the history of science. In the book, Newton described his three laws of motion and thus revolutionized human understanding of the physical universe.

Six years later in 1692 Newton suffered a nervous breakdown. The symptoms included insomnia, deep depression and debilitating paranoia. This crisis in Newton’s life is known as his ‘Black Year’, a period during which even his closest friends and associates thought he had gone insane.

Newton eventually recovered his mental faculties but had seemingly lost all interest in science. He turned his attention instead to the study of alchemy and the search for hidden meanings in the Bible.

In 1696 he became a civil servant, taking an administrative job at the Royal Mint. The world’s greatest physicist, mathematician and natural philosopher was to remain in this position until his death, thirty years later.

The cause of Newton’s breakdown and his subsequent retirement from science was not known during his lifetime and remained a mystery thereafter.

Newton’s Epitaph by Alexander Pope:

Nature and nature’s laws lay hid in night;

God said, ‘Let Newton be’ and all was light.

IN CONSTANTINOPLE, ON

a bright, chill early morning in June 1914, Hugh Stanton, retired British army captain and professional adventurer, leant against the railings of the Galata Bridge and stared into the waters below. There was a stiff breeze blowing and the early light sparkling on the gun-metal river made the choppy crests twinkle like stars.

Stanton half closed his eyes and forgot for a moment that this was the mouth of the Bosphorus, ancient sewer of Byzantium, and imagined instead a heavenly firmament. A faraway galaxy dotted with infinite points of divine light. A gateway to an incandescent oblivion.

Opening his eyes wide once more he saw the river for the poisonous shit soup that it was and turned away. If he ever did decide to kill himself a bullet would be quicker and a great deal cleaner.

The morning traffic creaked and rattled across the newly metalled bridge and Stanton found his eye focusing on a woman in a burka on the opposite side. She had been bending low over the sweets and pastries on display at a coffee stall and now she turned away, a billowing black cloud followed by a small girl and an even smaller boy, both clutching paper bags into which they dipped sugar-coated fingers.

Stanton realized to his surprise that he was crying. Tears that had been prickling behind his eyes for months were all of a sudden glistening on his cheeks. Those children were so very like his own. Different colouring and clothing, of course, but in scale and attitude they could have been his Tess and Bill. Even the way the little girl put her hand on her brother’s shoulder to restrain him at the kerb, so proud of being the older and the wiser of the two. That was exactly what Tess would have done. Probably all big sisters were like that.

Angrily he wiped a sleeve across his cheek. He didn’t believe in self-pity. Not under any circumstances.

Just then the peace of the morning was disturbed by the throaty roar of an engine as on to the bridge from the northern side skidded an overloaded, open-topped tourer. Stanton recognized the model, a Crossley 20/25. Cars were a passion for him and he knew every British type ever built. The occupants of this one were all young men, well-heeled hooligans on a spree, braying and hollering, clearly still drunk from the night before.

Feringi

. Foreigners bent on mischief, coming down from the Pera district where the Westerner was king.

Pedestrians scurried for the pavements as the car clattered across the bridge, the driver beeping his horn and shouting as if this busy public thoroughfare were his own private driveway. Stanton heard English voices, merry laughter laced with effortless contempt. They were embassy staff perhaps, or servicemen in mufti; the British had a lot of military in town, advising the sultan on how to drag his army and navy into the twentieth century. Or, more importantly, trying to stop His Munificence from seeking advice on such matters from the Germans.

The young Muslim family who had been occupying Stanton’s attention were in the process of crossing the street when the car came into view, Mother concentrating on ensuring that the children avoided the various piles of horse dung that lay in their path. Now she swept up the boy with one arm and grabbed the girl with her other and began to hurry them towards the opposite side, a scurrying black flurry of burka and kids.

But then the little girl dropped her bag and, being only about seven and not quite as grown-up and mature as she liked to think, pulled away from her mother to retrieve it. The mother turned back in panic and now the whole family stood in the path of the oncoming car.

The massive machine bore down on them. Nearly fourteen feet long and six wide, it seemed to completely fill the bridge. Almost a ton and a half of wood, glass, rubber, brass and steel, a monster, roaring and trumpeting as it approached its kill, the great shining black fender arches framing its huge goggling eyes. The thrusting tusks of its sprung-leaf suspension threatened to skewer any soft flesh and young bone that lay in its path. Black smoke billowed from its rear. Sparks spat from behind its grille. No dragon of ancient legend could have seemed more terrifying or more deadly.

The monster was still perhaps some fifteen yards away from the terrified mother trying to hang on to the squirming little boy while pulling at the girl, who was frozen with fear. Any car Stanton had ever driven would still have had ample time to brake. But this was a very different type of machine, with primitive steel and asbestos disc brakes fitted only to the rear wheels. What was more, the stunned-looking youth at the wheel was drunk, and the road was wet with morning mist and covered in slippery horse dung. Even if the driver did manage to hit the brake, the wheels would lock and the beast would surely skid wildly for tens of yards, taking the woman and her little children with it.

These thoughts occurred to Stanton all at once and only in the most fleeting and compressed form for his whole being was already in motion, his body accelerating away from the railing against which he had been leaning with all the energy of a man who by both instinct and training kept himself in a state of permanent physical readiness.

The young mother turned, her coal-black almond eyes staring out from the letterbox window of her face covering, wide with terror as Stanton, having covered most of the distance between them, launched himself into a long dive with arms spread wide. He hit them perhaps a half second before the car would have done, he and the little family passing in front of the oncoming machine with so little time to spare that the fender knocked Stanton’s foot as it swept by. He felt himself turning in mid-air, the family still gathered in his arms, causing the whole group to spin almost full circle as they crashed down on to the stones together.

The monster bumped and skidded on its way, horn still tooting and its braying occupants shouting more merrily than ever, pleased if anything with the terror they had caused. It was time sleepy old ‘Istanbul’, as the locals still insisted on calling it, recognized that the pace of life in Turkey was changing. If they wanted to be a Western nation they’d better learn to act like one, and they could start by getting out of the way of traffic.

Stanton was lying on top of the woman. Her veil had been dislodged and his cheek lay against hers. He felt her hot breath gusting past his ear and her breast heaving against his body. The little boy was half caught between them and the girl stretched out alongside.

He got quickly to his feet. This was Ottoman Turkey after all and the woman was clearly highly orthodox. While he couldn’t imagine even the most conservative of mullahs taking exception to the physical contact he had been forced to make, it was still an uncomfortable and threatening intimacy. He didn’t want an irate husband getting the wrong end of the stick and reaching for the long curved knife so many of the locals wore openly on their belts.

He had a job to do, and currently his first duty was to leave no trace.

He helped the young mother to her feet as she stuttered her thanks. Or at least he presumed they were thanks. She was speaking Turkish, which he recognized but did not understand. However, the gratitude in her eyes as she readjusted her veil would have been clear in any language.

People were gathering round, babbling in a variety of languages. Besides Turkish, Stanton recognized Greek, French and Arabic, and there were certainly others. The Galata Bridge must have been the most cosmopolitan thoroughfare on earth. Babel itself could scarcely have been any more polyglot.

‘I’m very sorry, uhm, madam,’ Stanton began in English, not quite sure how to address the woman, ‘but I don’t speak—’

‘She’s saying thanks, although I’m sure you guessed that,’ a voice said at his shoulder. Stanton turned to face a middle-aged man in the ubiquitous linen suit and straw boater of the European nabob. ‘She says you saved her children’s lives, and hers, which of course you did. Neat bit of work, I must say. You shot across the bridge like you had the bailiffs after you.’

A man in a uniform pushed his way through the crowd. Stanton thought he was probably a policeman but he may have been some sort of militia or even a postman. Turkish officials loved an extravagant uniform.

He felt someone take his hand and shake it.

Someone else slapped his back.

An old French gentleman seemed to be offering to stand him a drink, although by the look of the man’s red and bulbous nose this was more by way of grabbing the excuse to have an early one himself.

This was all wrong. His duty was to pass through the city like a shadow and suddenly he was the epicentre of a crowd. He needed to get away.

But the young mother kept thanking him; holding up her crying children, her big dark eyes shining with gratitude, thanking him over and over again.

‘You – my – babies,’ she said in slow, faltering English.

Her meaning was clear. He had saved her babies, nothing in the world could be more important.

But he hadn’t saved his own.

How could he have done? His family had never even been born.

IN CAMBRIDGESHIRE, IN

the early morning of Christmas Eve 2024, Hugh Stanton, retired British army captain and professional adventurer, was riding his motorbike through the frozen dawn.

There was thick mist on the ungravelled, icy road and the markings had long since faded from the potholed tarmac. If Stanton had deliberately sought out the most treacherous and deadly conditions in which to ride a powerful motorcycle at high speeds he would have struggled to find better.