Time of the Beast

Authors: Geoff Smith

Dedalus Original Fiction in Paperback

Time of the Beast

Geoff Smith was born in London and educated in Surrey. He worked in travel, then wrote and performed for theatre, television and radio before starting his own business. He is also a qualified psychotherapist.

Time of the Beast

is the result of his longstanding interest in Anglo-Saxon history and literature, along with a fondness for classic horror stories.

Now Grendel, with the wrath of God on his back, came out of the moors and the mist-ridden fells…

Beowulf

Then in the stillness of the night it happened suddenly that there came great hosts of the accursed spirits, and they filled all the house with their coming; and they poured in on every side, from above and from beneath, and everywhere. They were in countenance horrible, and they had great heads, and a long neck, and lean visage; they were filthy and squalid in their beards; and they had rough ears, and distorted face, and fierce eyes and foul mouths; and their teeth were like horses’ tusks; and their throats were filled with flame, and they were grating in their voice; they had crooked shanks and knees big and great behind, and distorted toes, and shrieked hoarsely with their voices; and they came with such immoderate noises and immense horror, that it seemed to him that all between heaven and earth resounded with their dreadful cries.

From

The Life of St. Guthlac, Hermit of Crowland

, by Felix of Crowland.

Translated by Charles Wycliffe Goodwin.

Chapter One

Greetings, traveller. You may approach. The night is cold, but my fire is warm and it holds the darkness at bay. Come, you may see that I am an old man who means harm to no one. I will be glad of your company. Settle yourself, eat and drink if you will; find companionship and respite from your journey. My own journey? It is nearly over – in every sense. As I sit here I contemplate the darkness as it stretches before me. I see how the night lives, stirred into motion by the leaping flames until the shadows appear to creep and circle about us like spirits that prowl at the gateway to another world. It brings to my mind images from long ago – a time when I wandered deep into the Otherworld on an expedition whose memory seems to me now like a mad and terrible dream.

You wish to know my story? But you will have guessed by now that it is not a comforting tale. Yet it may serve to instruct you, or at least divert you until the morning comes. Very well. Let us look together deep into the shadows which enclose us, and hope that chaos may come to take on the semblance of order.

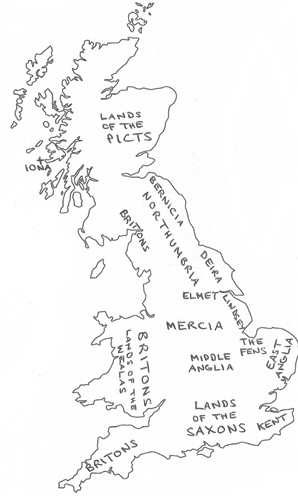

It was in the year six hundred and sixty-six of our Christian Age that I, Athwold, a monk, was given leave by my abbot to depart the monastery in the kingdom of East Anglia which had been my home for eleven years, to become at the age of twenty-five a hermit in the great marshland of the Fens. If you have never journeyed in the Fenlands – and I doubt that many ever find cause to do so – it is difficult for me to convey adequately in words just what a forbidding territory that dismal place is. A grim and desolate wasteland of dense high grasses and rushes, a perilous labyrinth with creeping fogs that will rise in a moment to close upon the unwary traveller, leaving him to stumble blind and lost through twisting, treacherous pathways amongst black quagmires and sucking pits that will pull him in an instant to his death. There are foul and stagnant pools, streams and rivulets which abound with leeches, stinging flies and all manner of vile parasites; and worst of all are the foul-smelling miasmas which float above the tainted waters, creating a poisonous atmosphere of unremitting gloom in a land of misty and near-perpetual twilight. The very gateway to Hell. In short, the ideal place for a religious retreat.

The Fenland is vast, almost a murky kingdom in itself, and its depths stand uncharted and ungoverned beyond every law of man; the natural refuge of outcasts, outlaws and other still worse things of ill omen. I journeyed there first upon a bright, sharp spring day to a settlement situated on the flat grasslands close to the western edge of the Fens, accompanied by my guide, a native man named Wecca, whose services had been arranged for me by the local Christian mission. No man knew these lands better than he, Wecca assured me, and he would lead me deep into the marshes to find some suitable place of refuge for me. He was a man approaching middle-life – I judged him to be about thirty – and he told me how in his youth he had gone to fight for the Christian King Anna of the East Angles in his war against old King Penda, the last pagan ruler of the kingdom of Mercia. Wecca was a handsome man with clear, pale blue eyes which beamed out from the wild tangle of his flaxen hair and beard. He looked to me like an angel peeping through a bush.

The village we approached was a typical farmstead, surrounded by pastures full of grazing cattle and sheep. It was clearly a prosperous place with many timber structures of varying sizes, their thatched roofs visible from miles away as they poured clouds of grey smoke into the open sky. The whole village was encircled by a protective trench and a palisade. I would spend the night at this outpost, then tomorrow begin my search in the Fens for the place of my seclusion.

As we drew near, Wecca blew on the brass horn that hung from his neck to signal our presence. The men of the village soon emerged in a crowd to greet us, clad in their brightly coloured woollen tunics and dark trousers, some with long cloaks held at the shoulders by ornate bronze clasps. They carried spears, but only from habit, it seemed, for our arrival was expected and their faces were welcoming and friendly. These men were of the tribe called Gyrwas, or fen-men, a famously independent people, for they knew themselves to inhabit the fringes of a land where no king might assert his rule effectively. But it encouraged me to see that a roughly made wooden shrine to the Cross stood at the gateway to their village. The men treated me with respect and reverence, regarding me as a kind of holy man. And, I learned later, a brave one.

I was taken to a guest hut, a place quite comfortable by the standards of a monk accustomed to only a bare cell. I had learned to distrust comfort, but I consoled myself with the thought that soon I would know little enough of it. The village outside was intolerably noisy with the grunting of pigs, the clucking of hens and the incessant screaming of small children. It would be almost impossible, I concluded sadly, for a man to clear his thoughts sufficiently to reflect upon God in a place of so many distractions. And the stink was abominable.

That evening I was led along a muddy pathway to the village beer hall, where a feast had been prepared in my honour. I would not have wished for such a thing, but I knew that hospitality was regarded as a tradition and a duty by these people, even when it meant that all might starve for it later.

When I entered their hall – dark, smoky and filled with the warm smell of cooking meat – the men rose from their benches out of respect, and were not seated again until I was escorted into the chair of the high guest. This made me feel uneasy. I was not a bishop or a priest, or any Church dignitary, only a humble monk passing through; and in those days I was much concerned with humility, or at least the outward appearance of it. Nevertheless it gratified me that these men honoured the Church through me. They were God-fearing people. So it seemed.

Soon the great iron cooking pot which stood on high trestles above the fire was lowered to the ground by dark-haired Celts, slaves in rough tunics and crude metal neck-bands to denote their lack of status. They carried the food to us on huge wooden platters: venison and fowl, along with sausages and blood puddings, and loaves of freshly baked bread. And there was also much strong drink: the milder ale and the more potent beer. I drank only a cup of the ale mixed with water and ate mostly bread with an occasional mouthful of chicken, for my order prohibited the consumption of red meat. To find the right balance was important, for I must demonstrate my appreciation while appearing to remain appropriately abstemious. Only the village men were present at this banquet: perhaps they considered women unsuitable company for a celibate monk. I thought this view most proper. When we had finished eating, we were subjected to the verses of a

scop

– a bard who plucked with indifferent skill upon a lyre, while reciting some interminable heathen tale about a hero who battled with a monster in a marsh.

As the evening went on, the men about me became increasingly drunk – to my growing concern and disapproval – until at last it seemed that I was the only sober man left in the hall. But with drunkenness they became more bold and outspoken, and some of the distance between us appeared to diminish – until then they had seemed like shy, awkward children who did not know quite how to address me. Yet now they began to overcome their timidity and questioned me openly about my intention to live as a recluse in the Fens. As light from the torches which hung from iron sconces on the flame-blackened walls bathed their bushy, bemused faces, it was clear that the notion was wholly inexplicable to them, even on the part of an inscrutable holy man.

‘Do you know?’ they whispered, crowding about me as their eyes grew wide and their faces darkened. ‘There are bad things. Out in the fen. Bad things in the darkness. In the night.’

Of course it was clear to me that the Fens must contain a multitude of natural perils. This must be obvious to anyone, and it was what made those sparsely populated wastelands the place of solitude I sought. But the manner of these men seemed at once guarded and fearful in a way that did not suggest a concern for natural things. To my further questions they did not reply directly, but merely cast ominous glances at each other and mumbled evasively as they shook their heads. None were by now sober enough to remember to make the sign of the Cross while they muttered darkly, if only as a gesture to please me.

I nodded at them gravely as I began to understand. They would not speak openly of their credulous terrors, fearing a primitive superstition that they might be heard by something outside – something grim and malevolent – and give it power over them. ‘To speak of the Devil is to bid him come’, as the saying goes.

I felt sudden anger towards these simple-minded men, and in my heart I began to despise them, although I told myself that my feelings were rather those of pity. In my younger days I had turned from the old pagan beliefs of my ancestors to embrace with zeal the new Faith of Christ. I knew with all the certainty of youth that our Church was the shining beacon of the one true God, which would lead men out of darkness and into the light. It would unite the petty scattered kingdoms of Britain under a single discipline and creed, even to make us one with our brother-lands in Europe. I never doubted that the Church would succeed in its holy mission to civilise our world, to foster learning and bring wisdom, to broker peace and lead us beyond the tribal rivalries and wars that so often lay waste to our fragmented lands. It was only a question of how long these things would take. And I had every reason to be optimistic. For I had seen in my own short lifetime the remarkable triumphs of the Church over the dark ways of paganism; and by the time I went into the Fenlands every Angle and Saxon kingdom of Britain, save for the backward South Saxons and the barbarous inhabitants of the island called Wight, had been won over to Christ. Kingdom by kingdom, region by region, we had taken these lands, replacing heathen idols with Christian ideals.