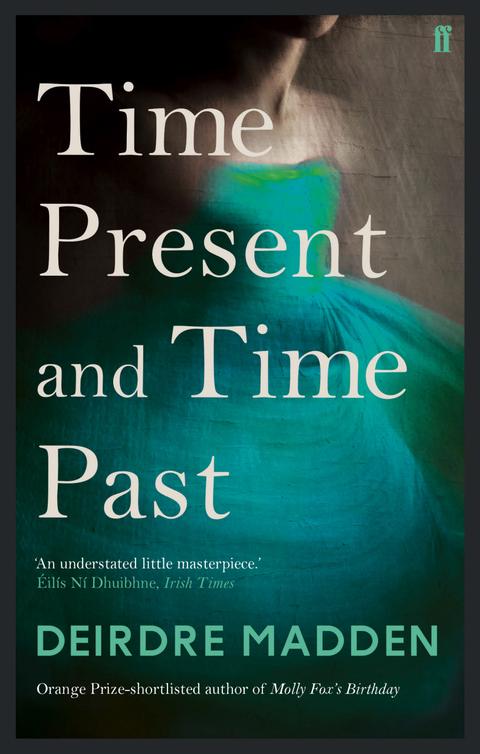

Time Present and Time Past

Read Time Present and Time Past Online

Authors: Deirdre Madden

Deirdre Madden

For Lara Marlowe

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future,

And time future contained in time past.

T. S. Eliot, ‘Burnt Norton’

Where does it all begin? Perhaps here, in Baggot Street, on the first floor of one of Dublin's best restaurants, on a day in spring. It seems as good a place to start as any. Fintan is sitting at table before the

ruins

of a good lunch, with crumbs on the tablecloth and empty wine glasses, together with half-empty bottles of mineral water, both still and sparkling. There are two tiny coffee cups on the table, and a crumpled white linen napkin discarded on the place opposite. One might imagine that a disgruntled lover has just flounced off, but Fintan, faithful as Lassie, is not that kind of man. His lunch companion has been a business associate and the encounter has not gone well; it has been both strange and unpleasant. For now, Fintan dwells on the unpleasantness, and on the lunch itself.

He has eaten a fine sea bass, that most fashionable of fish, but, distracted by the obstinacy of the other man, he has not particularly enjoyed it. He feels

irritated

too, because when the waitress brought dessert menus his companion had waved them away, even though he, Fintan, was the host. They ordered espressos and the other man threw his back as though it were a shot of vodka, then said he must leave. It was a cool parting. Fintan broods on all of this and eats the chocolate almonds that came with his coffee. Instead of solving problems with the help of hospitality, as he had intended in arranging the lunch, it has further complicated and compounded the difficulties. He eats the chocolate almonds that came with the other man's coffee. It is Ireland in the spring of 2006 and failure, once an integral part of the national psyche, is an unpopular concept these days. Fintan feels the snub of the dismissed dessert menus with particular keenness.

His full name is Fintan Terence Buckley and he is forty-seven years old. He is a legal advisor at an

import

/export firm, and a more successful man than he feels himself to be. He has been married to Colette, who is the same age, for twenty-four years. They live in Howth and have two sons: Rob, who is studying Business and Economics at University College Dublin; and Niall, who is in his first year of Art History and English at Trinity. They also have a daughter, Lucy, who is seven.

He finishes his coffee and settles the bill. As he goes downstairs, to his dismay he recognises two of the diners in the packed ground floor: his mother Joan and her sister Beth. He feels a further stab of dislike for the man who walked out on him, and who would have been the perfect decoy at this moment, for he could have swept past with little more than a smile and a greeting. Now he cannot avoid them. He tells himself he is being foolish. It will be good to talk to Beth. He tells himself not to get annoyed, no matter what his mother says to him. He buttons the jacket of his suit, unbuttons it, buttons it again and then crosses to where they are sitting.

âHello Mummy, hello Auntie Beth.' Fintan hates calling his mother âMummy'. It makes him feel like a little child, but she resists âMum' and all other alternatives. They exchange greetings, a flurry of air kisses and grey hair, soft flowery scent. His mother is formidable in fuschia; Beth is wearing a navy suit.

âThis is a lovely surprise,' Beth says. Both women have menus in their hands; they have yet to order their meal. Beth urges him to join them and he replies that he has just lunched with a colleague.

âYou call it work, I suppose,' his mother says. âIsn't it well for some. Work indeed.' Given that the lunch was most definitely to be filed under work, this

irritates

Fintan. He is doubly irritated, because he had resolved not to let his mother annoy him, and she has succeeded in doing so in less than a minute. He doesn't respond but says to Beth, âWhat are you thinking of having?'

âAnd you'll have had a pudding, too, if I know you,' his mother goes on, ignoring the fact that she is being ignored.

âI didn't,' Fintan says. She reaches out and jabs him in the stomach with her index finger.

âYou'll go home tonight and have another full dinner. No wonder you're the shape you are. Look at you!' And she jabs him again.

âAh leave him be, Joan,' Beth pleads, âisn't he grand? I'm thinking of having the sea bass, Fintan.'

âIt's the wrong day of the week for fish,' Joan says, turning her attention to the menu again. âIt can't possibly be fresh. They'll give you some old thing that's been lying in the fridge since last Friday.'

âIt sounds rather good,' Beth says. âIt comes with spinach and new potatoes.' Fintan tells her that it is good, that he had it himself and that it was both delicious and fresh.

âHave the lamb, Beth,' Joan says. âThat's what you want.'

If she wants the lamb then why is she saying that she wants the bloody sea bass?

It's a mercy Martina isn't here, Fintan thinks, or there'd be war. A foreign waitress comes to the table, wearing a shirt and tie and a black waistcoat. The lower half of her body is wrapped in a long white linen apron and she is holding a notepad.

âAre you ready to order?' Fintan puts his hand lightly on Beth's shoulder and says, âThis lady is having the sea bass, and might I suggest a glass of Sancerre to go with it. Mummy, you were interested in the lamb?'

âI'll have the beef, and a glass of Brouilly, if I'm let,' she says, snapping the menu closed and holding it out. The waitress proposes mineral water and then leaves.

Because his sister is in his mind Fintan asks Beth, âHow's Martina doing these days?'

âShe's very well. She was talking about you only last evening. Come and see us, we'd love that.' She asks after Colette then, asks about Lucy and the boys. Her gentle sincerity soothes Fintan after his run-in with his mother, at whom he glances as he talks to Beth. Joan is still bristling, like a cat that has been pushed out of its favourite chair. Beth throws her a few easy conversational openings, but she does not respond. She sits there, staring at her own hands, which, Fintan notices, look considerably older than the rest of her. The bright stones of her rings, rubies, an emerald, their startling colours, are disconcertingly at odds with the mottled and gnarled fingers that display them. Now Fintan feels small and mean for being angry with such an elderly woman, particularly one who happens to be his own mother.

But she started it.

Thinking this makes him feel smaller still, and meaner.

The waitress returns with the wine. He wishes them well for their meal and takes his leave.

*

He walks up Baggot Street, up Merrion Row, past offices and busy shops, past other restaurants full of patrons like himself, businessmen in suits. As he goes, he tries to rationalise to himself the irritations of the day. True, he has let Joan annoy him, but against that, he in his turn has annoyed her and, perversely, this makes him feel better. He reflects that, compared to his sister, he has a relatively good relationship with their mother. Had he not already been in poor humour because of his unsuccessful meeting, he might well have found the encounter tolerable. But today he feels sufficiently bothered and dispirited not to want to go back to work immediately. He sees Stephen's Green ahead of him and decides that he will go in there for a moment to clear his head.

Fintan crosses the road and enters behind the statue of Wolfe Tone. He walks along the lovely alley of lime trees and then turns towards the water. Up on the humpbacked stone bridge he looks left, to where a lone mallard is dragging a vast triangular wake across the still surface of the pond. There are more birds on the other side of the bridge, mallards and moorhens and swans. Children are feeding them bread and as Fintan watches he thinks of his own daughter Lucy. Lucy, whose conception he had resented, whose birth he had dreaded, and whom he loves (he can admit this only to himself) more than anyone else in his life. He will bring Lucy here so that she too can throw crusts to the birds. He will take her to the playground in the Green; he will point out squirrels in the trees; he will lay down memories for her to enjoy in the years ahead, like fine wines maturing in a cellar. But when he tries to visualise Lucy as an adult, as the woman who will savour these memories, he cannot do it. All he can see is a pearly mist: something like ectoplasm.

For all that, Fintan already feels happier than he was when he left the restaurant. He walks on to where the Green opens up into a series of gaudy flowerbeds and he stops to check his phone. There is a voicemail from his assistant saying that his three o'clock meeting has been cancelled, and this cheers him further. He texts Colette to ask what's for dinner. Unusually, he decides to take a somewhat freeform approach to the afternoon. He will not go back to the office just yet. He will go and have a cup of coffee, and perhaps something sweet to make up for being gypped out of his dessert. His phone chirps twice.

Roast chicken thought u had lunch out 2day?

Fintan doesn't reply but continues on to the Ranger's cottage, and this too he resolves to point out to Lucy. It will be pleasing to a child, this gingerbread house, with its exaggeratedly steep roof and elaborate edging, its tiny bright garden and boxwood hedges, absurdly pretty. He leaves the Green by the gate behind the cottage and crosses over to Harcourt Street, and goes into a cafe there.

At the counter he orders a latte and a piece of carrot cake. (Unfortunately Joan is correct: he does need to lose weight.) The waitress hands him the cake and says she will bring the coffee down to him. There are bentwood chairs and marble-topped tables in the cafe. From where he chooses to sit, Fintan can see out into the street, to the little wooden terrace where the smokers sit. He can also see a wall hung with black-and-white photographs of Dublin at the start of the twentieth century. There is the famous one of the train accident at Harcourt Street Station, the locomotive slammed right through the wall and out the other side, like a toy an angry child had broken in a rage; and there are pictures of the streets Fintan himself has recently walked, of the Green itself, but peopled here with citizens in long awkward dresses and bustles, kitted out with parasols and hats. There is pop music on the radio, one of the FM stations with chatty DJs to cheer people up, to get them through the day, to distract them with things they will immediately forget.

The waitress brings the coffee. The cake, which he now opens and starts to eat, is packaged in a small cardboard sleeve, the whole thing wrapped in cellophane. On one side are the words âA Sweet Treat' and on the other side âCarrot Cake'. As Fintan drinks his latte, he listens to the music and gazes absentmindedly at the words âCarrot Cake' until all meaning drains out of them. The letters are just shapes, random and arbitrary, and have no connection to what they describe. They might as well be written not just in a foreign language but in a different

alphabet

, might as well say бÐСÐÐÐТ or ΤΤανΤΣÎΤάνί. Fintan is aware that this kind of thing is not so unusual, that pretty well everyone has had this experience of looking at a word somewhere until the meaning detaches from the word itself, although they tend to come together again as soon as one becomes aware of it. But it isn't just words and language that are becoming strange to him, it is objects too. What had been in the cardboard sleeve now looks unspeakably bizarre to him: the moist terracotta crumbs; the coarse bright-orange shreds laced through it; the heavy parchment-coloured cream in which is embedded a thing, a hard, dark wrinkled thing that looks like the pickled brain of an elf. And now, like the fading of a dream, Fintan gradually becomes aware of the object before him for what it is: a half-eaten piece of carrot cake with a walnut on top.

What rattles him is that this is the second time today that such a thing has happened. When he had been having lunch, at a certain point he had stopped hearing, or indeed listening to, what his companion was saying. The other man had stopped being a person with whom Fintan was communicating, and had become instead a kind of phenomenon which he was observing. It was as if the air had thinned out and the man was like something that had dropped out of the sky. Fintan had stared at his face, which was florid, at the way his bulging neck flowed over the hard edge of his shirt collar. The lilac silk tie had a luxurious sheen; he noticed the way there was a kind of white light in where it curved in the knot. Maybe it was something of the contrast between his companion's imperfect body and the expensive details of his attire that had triggered all of this. And all the time he was staring at him the man was talking, about what Fintan had no idea. He couldn't even hear him properly; it had been like watching a film with the sound turned down. Suddenly he realises that this might well be a reason why the meeting had gone so badly: he had perhaps missed some important point that the other man had made, or the man had become aware that Fintan wasn't mentally present in the way he should have been, and this had perplexed or even annoyed him. And now this strange thing in the cafe.

He tells himself to get a grip. He looks again at the photographs. There is a dislocation between the familiarity of the locations and the strangeness of what is shown: the clothes, the transport. The trams in the pictures are packed and seem too small to be taken seriously, with people hanging off the top as if they could only be riding along for a lark, rather than for necessity. Dublin at the start of the twentieth century looks cluttered and weirdly complex, with the fussy dresses of the women, with the elaborate shop fronts. Fintan suddenly realises that he finds it difficult to believe in the reality of these scenes. He can no more imagine himself on the streets alongside these people, who lived in the same city as him, than he can imagine himself as a figure on a Grecian urn. Is it because the images are in black and white that they seem irredeemably distant? But once Beth had shown him a photograph which reconciled the past and the present: an Edwardian miss with a straw hat, some long-forgotten ancestor of theirs, who bore an extraordinary resemblance to Fintan's sister Martina. And he remembers now also a remark Lucy had made once when they were trawling through a box of old family photographs at home: weddings, rainy picnics, late lamented terriers. âWhen did the world become coloured?' It had taken him a moment to understand what she meant, and then he thought he had never heard such a delightful notion. He loved the idea of a monochrome world suddenly flooded with colour.