Time Travel: A History (20 page)

Read Time Travel: A History Online

Authors: James Gleick

Tags: #Literary Criticism, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Science, #History, #Time

—

THE TIME CAPSULE IS

a characteristically twentieth-century invention: a tragicomic time machine. It lacks an engine, goes nowhere, sits and waits. It sends our cultural bits and bobs traveling into the future at snail’s pace. At our pace, that is. They travel through time in parallel with the rest of us, at our standard velocity of one second per second, one day per day. Only we go about our business of living and decaying, while the time capsules try, ostrichlike, to evade entropy.

Builders of time capsules are projecting something forward into the future, but it’s mainly their own imaginations. Like people who buy lottery tickets for the momentary dreams of riches, they get to dream of a time to come when, though long dead, they will be the cynosure of all eyes. “A story of international importance and significance.” “Prominent men from all over the world assemble.” Clear the airwaves: Dr. Thornwell Jacobs, Oglethorpe University, AD 1936, has something to say.

Looking backward, they misconstrue the intentions of their ancestors. They have the disadvantage of hindsight. Cornerstones of new buildings have long been repositories for inscriptions, coins, and relics, and now, when demolition crews stumble across such items, they mistake them for time capsules and summon journalists and museum curators. For example, in January 2015, many news organizations in the United States and Britain reported the “opening” of what they called “the oldest U.S. time capsule,” supposedly left to us by Paul Revere and Sam Adams. This was in fact the cornerstone of the Massachusetts State House, dedicated in 1795 at a ceremony attended by Adams, then the governor, along with Revere and William Scollay, a real-estate developer. The cornerstone memorabilia were wrapped in leather, which naturally deteriorated. In 1855 they were found during foundation repairs and reburied, this time in a brass box the size of a small book, with some extra new coins for good luck, and in 2014 State House workers uncovered the box while trying to trace some water damage. This time, it was thought to be a time capsule. The “air channels of the radio-newspaper and world television broadcasting systems” were not cleared, but several reporters showed up and video cameras rolled as museum conservators examined the contents: five newspapers, a handful of coins, the seal of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and a dedicatory plaque. From these items what could be inferred? The Associated Press interpreted them this way:

Early residents of Boston valued a robust press as much as their history and currency if the contents of a time capsule dating back to the years just after the Revolutionary War are any guide.

“How cool is that?” one of the archivists was quoted as saying. Not very. The correspondent for Boston.com, Luke O’Neil, injected a rare note of skepticism: “

Behold these great wonders from the past!

today’s press is proclaiming,

a printed broadsheet newspaper and a currency made out of metal.

” These items had nothing to tell us about Paul Revere or Sam Adams or the life and furniture of post-Revolutionary Boston, nor were they ever meant to. The curators decided to seal them up with plaster once again.

Cornerstone deposits are almost as old as cornerstones. They were not messages to people of the future but votive offerings, a form of magic or sacred ritual. Coins dropped in fountains and wishing wells are votive offerings. Neolithic people entombed axe hoards and clay figurines, Mesopotamians hid amulets in the foundations of Sargon’s palace, and early Christians cast tokens and talismans into rivers and buried them in church walls. They believed in magic. So, evidently, do we.

When did eternity, or heaven—the afterlife outside of time—give way to the future? Not all at once. For a while they coexisted. In 1897, the Diamond Jubilee year of Queen Victoria, five plasterers completing the new National Gallery of British Art on the site of the old Millbank Prison penciled a message inside a wall:

This was placed here on the fourth of June, 1897 Jubilee Year, by the Plasterers working on the Job hoping when this is Found that the Plasterers Association may be still Flourishing. Please let us Know in the Other World when you get this, so as we can drink your Health.

It was found in 1985 when the Tate Britain (as it had become) did some remodeling. The message remains, preserved on film, in the gallery’s archive.

If time capsulists are enacting reverse archeology, they are also engaging in reverse nostalgia. That feeling of sweet longing for past times—with some mental readjustment, we can feel it for our own time, without having to wait. We can create instant vintage automobiles, for example. In 1957, the semicentennial year of Oklahoma statehood, a new Plymouth Belvedere with shiny tail fins was buried in a concrete vault near the statehouse in Tulsa, along with a five-gallon can of gasoline, some Schlitz beer, and some useful trinkets in the glove box. It was to be exhumed fifty years later and awarded to a contest winner. And so it was. But there were better ways to store antique cars. Water seeped in, and what Catherine Johnson, ninety-three years old, and her sister Levada Carney, eighty-eight, received was a rusted shell. Tulsa was undaunted. In 1998 the city laid to rest a Plymouth Prowler, for another fifty years.

The craze has become a business, the “future packaging” industry. Companies offer time capsules in a range of styles, colors, materials, and price points, just as mortuaries market coffins. There are extra charges for engraving and welding. Future Packaging and Preservation promotes Personal Sally, Personal Arnold, Mr. Future, and Mrs. Future cylinders. “Are you on a tight budget? Our

Cylindrical Time Capsule

style may be the most practical choice. Always in stock, these capsules are made of stainless steel, are pre-polished, pre-marked on the bottom with the phrase ‘Time Capsule.’ ” The Smithsonian Institution offers a list of manufacturers and gives professional tips: argon gas and silica gel are good, PVC and soft solder are bad, and as for electronics, “electronics are a problem.” Of course, the Smithsonian has a related business model. Museums conserve and preserve our valuables and our knickknacks for the future. With a difference, of course: museums are alive in the culture. They don’t hide the best stuff away underground.

Far more time capsules are buried than are ever recovered. Hermetic as these efforts are, “official” records do not exist, but in 1990 a group of time-capsule aficionados organized a so-called International Time Capsule Society, in hopes of creating a registry. The mailing address and website are at Oglethorpe University. In 1999 they estimated that ten thousand capsules had been buried worldwide and nine thousand of those were already “lost”—but lost to whom? Inevitably the information is anecdotal. The society lists a foundation deposit believed to lie under the Blackpool Tower in Lancashire, England, and says that both “remote sensing equipment” and “a clairvoyant” have failed to find it. The town of Lyndon, Vermont, is supposed to have buried an iron box during its centennial celebration in 1891. A hundred years later, Lyndon officials searched the town vault and other sites, in vain. When the television show

M*A*S*H

ended, its cast members tried to bury some props and costumes in a “time capsule” at the 20th Century Fox parking lot in Hollywood. A construction worker found it almost immediately and tried to give it back to Alan Alda. The time capsulists are trying to use the earth, its basements and graveyards and fens, as a great disorganized filing cabinet, but they have not learned the first law of filing: Most of what is filed never again sees the light of day.

—

A RESIDENT OF

New York City transported a thousand years into the past would not understand a word spoken by the people he encountered. Nor, for that matter, would a resident of London. How can we expect to make ourselves understood to people of the year 6939? Time-capsule creators tend not to worry about linguistic change any more than the science-fiction writers do. But, to their credit, the Westinghouse team did worry about making their time capsule intelligible to the scarcely imaginable recipients of their message. It would be an overstatement to say they solved the problem, but at least they thought about it. They knew that archeologists continued to struggle with ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs a century after the lucky breakthrough provided by the Rosetta Stone. Clay tablets and carved stones still surface bearing scripts from lost languages that defy translation—“proto-Elamite” and “Rongorongo” and others that have not even been named.

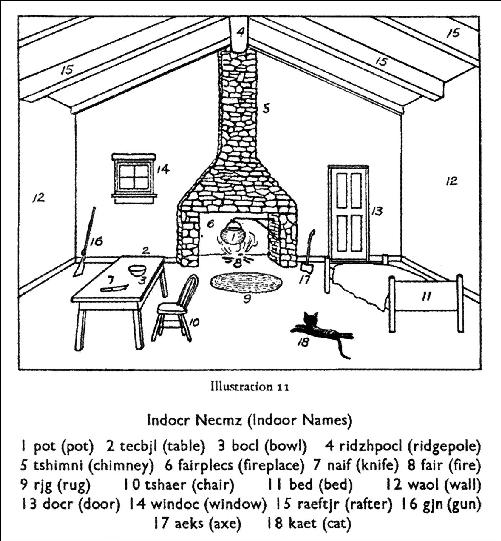

So the authors of the

Book of Record of the Time Capsule of Cupaloy

tucked in “A Key to the English Language,” by Dr. John P. Harrington, ethnologist, Bureau of Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. It comprised a mouth map (or “Mauth Maep”) to help with pronunciation of the “33 sounds of 1938 English,” a list of the thousand most common English words, and diagrams to convey elements of grammar.

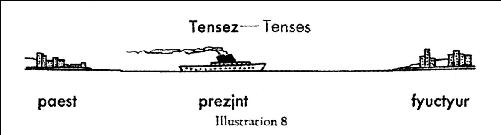

Also enclosed was an enigmatic one-paragraph story, “The Fable of the Northwind and the Sun,” repeated in twenty-five different languages—a little Rosetta Stone to help the archeologists of 6939. An explanatory drawing titled “Tenses” showed a steamship labeled present heading from the leftward city (past) to the rightward city (future).

Any effort of this kind confronts a bootstrap problem. The “Key to the English Language” is written, perforce, in English. It uses printed words to explain pronunciation. It specifies sounds in terms of human anatomy. What will our hypothetical future folk make of this: “English has eight vowels (or sounds whose hemming amounts to mere cavity-shape resonance)”? Or this: “The vowel with highest raised back of the tongue, that is, nearest to the

k

consonant position, is

u;

the vowel with the highest raised middle of the tongue, that is, nearest to the

y

consonant position, is

i

”? Who knows where their glottises will be, anyway, or whether those will have gone the way of gills?

The Westinghouse authors also imagined that librarians could continually retranslate the book to keep up with linguistic evolution. And why not? We still read

Beowulf.

They beseeched whomsoever: “We pray you therefore, whoever reads this book, to cherish and preserve it through the ages, and translate it from time to time into new languages that may arise after us, in order that knowledge of the Time Capsule of Cupaloy may be handed down to those for whom it is intended.” They would be glad to know that already, as of the twenty-first century, the book is back in print, copyright having been waived: available for around ten dollars from print-on-demand publishers, for ninety-nine cents in an Amazon Kindle version, and widely free online. On the other hand, libraries, short of space, have been “deaccessioning” their copies. Mine once belonged to Columbia University; later it made its way to a used-book dealer in Cleveland, Ohio. Are the librarians forsaking their duty to the future? No, they are fulfilling it, by continually choosing what to keep and what to let go. “We shed as we pick up, like travelers who must carry everything in their arms,” says Septimus in Tom Stoppard’s

Arcadia,

“and what we let fall will be picked up by those behind. The procession is very long and life is very short. We die on the march. But there is nothing outside the march so nothing can be lost to it. The missing plays of Sophocles will turn up piece by piece, or be written again in another language.”

The problem of how to communicate with faraway creatures, physiognomy and language unknown, continues to receive scholarly attention. It arose again when people started sending messages into deep space, in capsules like the Voyager

1 and 2

,

launched from Cape Canaveral in 1977. These vehicles are space travelers and time travelers, too, their progress measured in light-years. They each bear a copy of the Golden Record, a twelve-inch disk engraved with analog data via the technology, now obsolete, known as “phonograph” (1877–ca. 1987). There are several dozen encoded photographs as well as Sounds of Earth, selected by Carl Sagan and his team and meant to be played at

16

⅔ rpm. Just as the Westinghouse time capsule lacked space for a microfilm reader, the Voyager spacecraft could not carry a phonograph record player, but a stylus was thrown in, and the disk is engraved with instructional diagrams. The same conundrum occurs in the context of nuclear-waste disposal: Can we design warning messages to be understood thousands of years hence? Peter C. van Wyck, a communications expert in Canada, described the problem this way: “There is always a kind of tacit assumption that a sign can be made such that it contains instructions for its own interpretation—a film showing how to use a film projector, a map of the mouth to demonstrate pronunciation, recorded instructions for how to assemble and use a stylus and a turntable.” If they can figure it all out—decode the information engraved as microscopic waves in a single long spiral groove on a metal disk a half millimeter thick—they will find diagrams of DNA structure and cell division, photographs of anatomy numbered 1–8 from

The World Book Encyclopedia,

human sex organs and a diagram of conception, and an Ansel Adams photograph of the Snake River in Wyoming, and they may “hear” greetings spoken in fifty-five languages (

“shalom”; “bonjour tout le monde”; “namaste”

), sounds of crickets and thunder, a sample of Morse code, and musical selections such as a Bach prelude played by Glenn Gould and a Bulgarian folk song

*6

sung by Valya Balkanska. That, anyway, is one message sent to deep space and to the far future.