Time Warped (14 page)

Authors: Claudia Hammond

Some people make the future circle very large to represent the vast unknown ahead of us. I found myself doing the

opposite and making the future smaller than the past or present because, unlike the past, I have no idea what it holds, so for me it feels as though there’s less information to fit in there.

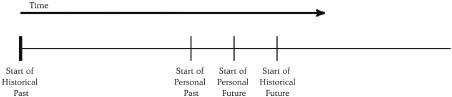

To examine further the way we perceive time in relation to our own lifespan and our place in history, Cottle used timelines. Draw a horizontal line and then make four marks on it representing the start of the following points in time – your personal past, your personal future, the historical past and the historical future after your life has ended. Here’s mine, but again there are no right or wrong answers – yours might be very different (and never mind whether Thomas Cottle thinks it is childlike).

Some people draw the timeline so that their own life takes up the majority of the space – an egocentric perception (within psychology this is not meant as a judgemental term); while others see their life as a short part of a longer line of the world’s past and future – a historiocentric perception. Back in the 1970s Cottle suggested that the historiocentric view suggests an ascriptive orientation – in other words you believe that it’s the past that affects your life, rather than your own efforts. He said upper-class people inheriting their wealth would be a good example.

44

An alternative of course is that the historiocentric view is put forward by

someone who remembers lessons at school on how short their life is in the context of human history, let alone the earth’s history. We were told that if the history of the planet is represented by the distance from your nose to your outstretched fingertip then one stroke of a nail file would wipe away all human history. Your own life within that would be too small to see.

The fact that when pressed we can all represent time graphically, and have a sense of a ‘correct’ way of viewing it, suggests that to an extent we are all able to associate time with space. Time is difficult to comprehend and difficult to grasp. It’s my contention that visualising it in space, even to a limited extent, makes it easier for us to grapple with. We constantly need to think about the past and future, and picturing their positions in relation to our bodies could simplify the concept for us. And as we’ll see, this association could even influence the metaphors we use in language. Or is it our language that affects the way we associate time with space?

TIME

,

SPACE AND LANGUAGE

When laying out either the circles or the timelines, English speakers invariably put the past on the left and the future on the right. You probably didn’t even consider laying it out the other way round; it just seems the obvious way to do it, whether or not you usually visualise time in space. Other experiments with random groups of people who have English as their first language have shown that almost everyone presented with flashcards printed with the words

past, present and future and asked to lay them out in order on a table will put them side by side in a horizontal line with past on the left, the present in the middle and the future on the right. What is driving this tendency? Is it evidence that most people do visualise time in space even if they’re not aware of it?

Rigorous testing has certainly shown that there is a strong association inside the minds of English speakers between the word ‘past’ and the position ‘on the left’. People are not just thinking ‘well, if I have to put the past somewhere I’ll put it on the left’. The association is stronger than that. Again the SNARC test provides the evidence. Tell people to hit a left-hand key whenever a word associated with the past is flashed on a screen and they will do it faster than if they are told to hit a right-hand key. The past and the left is just

right

somehow.

I’ve heard researchers suggest that this phenomenon can be explained by the direction in which the hands on a clock move. It’s true that the hands on a clock set off from the top of the hour in a rightward direction, so you could argue that this implies the future is off towards the right. But this is a theory that falls apart after 15 seconds, because after quarter past the hour the tip of the hand starts moving towards the left – time is going backwards into the past! Admittedly, by quarter to the hour the steady tick of time is now back on its rightwards trajectory – but only for 30 seconds. As you can see, this is going nowhere. We need a better explanation. More plausible, surely, is that English-speakers

read

from left to right. The very phrase ‘left to right’ illustrates the point. If you are reading that phrase in

English you read ‘left’ before you read ‘right’ – putting left before right in time. Or to put it another way, ‘left’ is in the past by the time you read ‘right’. And here’s the clincher perhaps. Arabic and Hebrew are written right to left on the page. Where do Arabic and Hebrew speakers place past, present and future on a left/right spectrum? With the past on the right, the present in the middle and the future on the left – the mirror image of English speakers. This then begs a much bigger question, and one which taps in to the debate that has raged for decades about whether language or thought comes first – does a Hebrew speaker think of the past as being on the right because she writes right/left or does she write right/left

because

she sees the past on the right?

Lera Boroditsky, a psychologist at Stanford University, has done some fascinating work comparing English and Mandarin speakers and the way they discuss time in terms in space.

45

The experience of time should be universal – a moment is with us and then gone; that happens wherever we live and whatever language we speak. But the way we describe that experience differs from language to language. Boroditsky found that speakers of both English and Mandarin use spatial references to horizontal and vertical planes when talking about time. The ‘best is ahead’ is horizontal, ‘let’s move that meeting up’ is vertical. But she found far more horizontal metaphors in English: we ‘put events behind us’ and ‘look forward to the party at the weekend’. In Mandarin people make more use of vertical metaphors – earlier events are ‘up’ or ‘shang’; later events are ‘down’ or ‘xia’.

Boroditsky stood next to people, pointed to a spot directly

in front of them and asked, ‘If this spot here represents today, where would yesterday and tomorrow go?’ Unlike tasks using computers, this technique had the advantage of being in 3D. If people saw time as a sash encircling the body, like some of my informants, they were free to point that out. Follow-up questions included: if the spot in front of you represents lunch, where do breakfast and dinner go, and if that same spot is September where would August and October go? She found that Mandarin speakers, whether living in Taiwan or California, were eight times more likely than English speakers to lay time out vertically, usually pointing up into the air for earlier events and down for later ones.

There would appear to be an obvious explanation for this difference. Traditionally, Mandarin is read in vertical columns, from right to left. That is changing however. These days it is often set out horizontally across the page from left to right, just like English. Yet the vertical conception of time has persisted and even the people who could

only

read Mandarin horizontally were still seven times more likely to arrange time vertically in space.

At one level expressions such as time ‘creeping up on us’ or ‘flying by’, are partly explained by our desire to keep our language fresh and lively. We do not

literally

experience time in this way. Having said that, the language we use to describe time does tell us something important about the essential character of our experience of time. Not least the capriciousness, strangeness and mutability of that experience.

With the exception of the language spoken by the Amondawa tribe in the Amazon where no word for time exists, most other

languages constantly make reference to it using words relating to space or physical distance. We talk of long holidays or short meetings, but rarely do we do this the other way round, borrowing the language of time to describe distance. We talk of time speeding up as though it were a physical object in space, like a car, but wouldn’t describe a street as four minutes long. But how much does this really tell us about the way we think of time? Do we use time-related phrases because they fit conveniently into our sentence structures or does this tell us something about the way we perceive time? Our experience of time is quirky and unsettling – and we come up with expressions that try to capture that feeling.

Is the way we think about time also influenced by the words we use? Psychologist David Casasanto compared the use of metaphors for ‘time as distance’ and ‘time as amount’ in four languages. In English we talk about something taking a long time (implying distance), whereas the Greeks use a phrase meaning physically large to refer to time and Spanish speakers refer to ‘

mucho tiempo

’ meaning much time. Using that handy research method of comparing numbers of hits on Google, Casasanto investigated whether the phrase ‘much time’ or ‘long time’ appeared most frequently. It was clear that French and English speakers preferred the use of ‘long’, the distance metaphor, while Greek and Spanish speakers used ‘much’, the amount metaphor. But the intriguing part of the study comes next.

46

A group of English and Greek speakers were given a series of tasks presented on a computer screen to investigate whether the way they

spoke

about time also affected the way they

thought

about it. Some tasks involved having to estimate how long it took a line to spread gradually across a

screen. Others involved guessing the time taken for a container to fill up with water. Some involved both. The results were clear: the English speakers were distracted by distance and allowed it to affect their estimation of time, while the Greek speakers were distracted by amount. However, Casasanto found that people’s loyalty to their language metaphors could be weakened; he was able to train English speakers to think of time in terms of amount instead of distance.

This experiment might seem obscure, but if it really is the case that the language you speak affects the way you conceptualise the relationship between time and space to the extent that it can change the judgements you make about speed, distance, volume and duration, then this is remarkable. This is a fairly new area of study, but you have to wonder what the implications might be. Could the words we use affect our whole attitude towards time?

TIME AND SPACE MIXED UP

Our use of language is not the only evidence demonstrating our association of time with space. In fact there’s more than an association. We get time and space mixed up. The father of developmental psychology, Jean Piaget, studied the way children’s minds work at different stages of their development. He conducted a study where two trains on parallel tracks move for exactly the same amount of time, but because one is going faster it stops several inches further away than the other. Young children insist that this train must have been moving for longer. Piaget concluded that young children find it hard to distinguish between size as

it relates to time and size as it relates to space. Children’s brains are of course still developing, but experiments conducted by Lera Boroditsky suggest that as adults we don’t find it much easier.

47

We are good at judging distances, but these judgements can skew our estimations of time. So if a series of dots are bunched together as they cross a screen we are likely to think they are moving faster than if they are more spread out, even though they are moving at precisely the same speed. We find it hard to judge time without allowing spatial considerations to come into play.

We are lucky enough to have complex brains that not only compute in many dimensions, but are

conscious

that they are doing so too. Our brains are very clever, but this cleverness can trip itself up. In this case, our brains are

fooled

by their very awareness that time and space are related. Bigger sometimes means faster, but not always. Lions are quicker than mice, but bullets are even faster. In everyday life we constantly make mental calculations involving speed, time and distance – think of catching a ball or crossing a road. So perhaps it’s not surprising if they are associated and sometimes confused in the mind. Show children two lights and ask them which was on for longest and they will choose the brighter one. Show them two trains racing and they’ll say the biggest one is the fastest. They get the idea of largest, but often apply it to the wrong property, which takes us back to the theory I discussed in the previous chapter: that we might have a neural structure which judges magnitude rather than time in particular. As adults we make fewer of these mistakes, but the relics of this space/time crossover are still there.

There is one rather mysterious element to all this: the way we think about time and space is not symmetrical. If you show people a line of three light bulbs, switch them on one at a time and ask people to guess the time between each light coming on, the more spread out the lights are physically, the longer people will say the duration between lights was. This is known as the ‘kappa effect’. It’s similar to the study with the series of dots moving across the screen, and also works the other way round. If you switch the lights on in turn and ask people to estimate the

distance

between them, the faster you turn on the lights, the closer they will say they are. This is called the ‘tau effect’. Just as we know a lion is big so it probably runs fast, we find it hard to ignore what we know about speed and distance and assume that faster probably means nearer. But Boroditsky and Casasanto have shown that the relationship between space and time is imbalanced. We think about time in terms of space

more

than we think about space in terms of time. This brings us back round to the language and the lack of phrases such as ‘a four-minute-long street’.

48