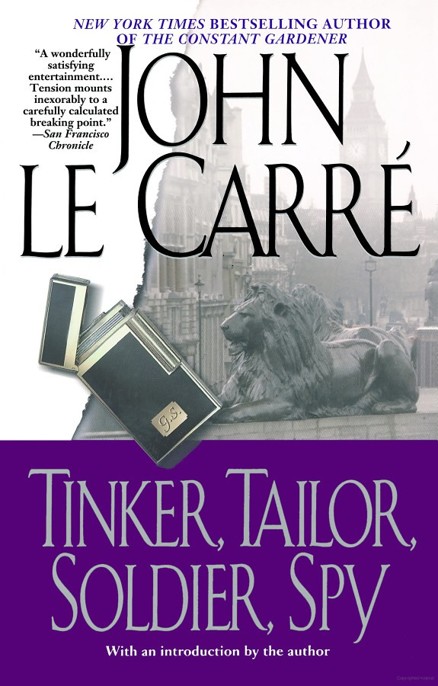

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy

Read Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy Online

Authors: John le Carre

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Thrillers, #Espionage, #Literary, #Suspense

Table of Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

TINKER, TAILOR, SOLDIER, SPY

JOHN LE CARRÉ, the pseudonym for David Cornwell, was a member of the British Foreign Service from 1959 to 1964. His third novel,

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold

, became a worldwide bestseller. He has written twenty-one novels, which have been published in thirty-six languages. Many of his books have been made into films, including

The Constant Gardener; The Russia House; The Little Drummer Girl

; and

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy

.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2 R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America by Alfred A. Knopf 1974

Published in Penguin Books 2011

Copyright © le Carré Productions, 1974

Introduction copyright © David Cornwell, 1991

All rights reserved

Grateful acknowledgment is made to The Clarendon Press for permission to reprint the

eight-line rhyme and descriptive paragraph from page 404 of the

Oxford Dictionary of Nursery

Rhymes,

edited by Iona and Peter Opie (1951).

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the

author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or

dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

eISBN : 978-1-101-52878-5

CIP data available

Set in Janson Text

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means

without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only

authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copy-

righted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

For James Bennett and Dusty Rhodes, in memory

TINKER,

TAILOR,

SOLDIER,

SAILOR,

RICH MAN,

POOR MAN,

BEGGARMAN,

THIEF.

Small children’s fortune-telling rhyme used when counting cherry stones, waistcoat buttons, daisy petals, or the seeds of the Timothy grass.

—from the

Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes

INTRODUCTION

I

have always wanted to set a novel in Cornwall, and to this day

Tinker Tailor

is as near as I ever came to doing so. The unfinished version that had lain in my desk drawer for years before I started writing the story in earnest did not contain George Smiley at all, but opened instead with a solitary and embittered man living alone on a Cornish cliff, staring up at a single black car as it wove down the hillside towards him. I had chosen in my imagination a spot not unlike the little harbour of Porthgwarra in West Cornwall, where the cottages lie low on the sea’s edge, and the hills behind seem to be pressing them into the sea. My man was holding a bucket in his hand, on his way to feeding his chickens. He had a limp, as Jim Prideaux has a limp in the version you are about to read, and like Jim he was a former British agent who had walked into a trap set for him by a traitor inside his own service, called “The Circus.”

My original plan was for the Circus investigators to put this figure back into harness, in a way that would provoke the unknown traitor to try his hand again, and thus reveal himself. I wanted the entire story to play in contemporary time and not in the flashbacks I later resorted to. But when I got down to writing the book for real, I discovered that I was painting myself into a corner. I could think of no plausible way to pursue a linear path forward while at the same time peering back down the path that had brought my man to the point where the story began. So one day, after months of frustration, I took the whole manuscript into the garden and burned it, and began again.

I had also saddled myself with another headache. I was determined to describe something that in those days was still new to my readers and perhaps, despite all the press revelations about the penetration of our secret services, still is even now: namely, the inside-out logic of a double-agent operation, and the sheer scale of the mayhem that can be visited on an enemy service when its intelligence-gathering efforts fall under the control of its opponent.

Oh, we knew vaguely that Kim Philby had once been head of the counter-intelligence section of the British secret service and privy to American efforts to penetrate the KGB. We knew that at one time he was in line to become chief of the entire British service. Perhaps we even knew that he had personally advised the CIA’s foremost Moscow Centre watcher, James Jesus Angleton, on double-agent cases, in which Philby was held to possess exceptional expertise. We had read perhaps that George Blake, another KGB traitor inside SIS, had betrayed a number of British agents to his Soviet masters—he now claims hundreds, and who is to deny the wretched man his boast? His cause, like his victims, is dead. But what very few people managed to understand was the pushme-pullyou nature of the double-agent’s trade.

For while on one side the secret traitor will be doing his damnedest to frustrate the efforts of his own service, on the other he will be building himself a successful career in it, providing it with the coups and grace-notes that it needs to justify its existence, and generally passing himself off as a capable and trustworthy fellow, a good man on a dark night. The art of the game—best described in J. C. Masterman’s account of the British double-cross system operated against Germany in wartime—is therefore a balancing act between what is good for the double agent in his role as loyal member of his service, and what is good for your own side in its unrelenting efforts to pervert that service to the point where it is doing more harm to the country that employs it than good; or, as Smiley has it, where it has been pulled inside out.

Such an abject state of affairs was certainly reached by SIS in the high days of Blake and Philby, just as it was self-inflicted on the CIA by the paranoid influence of Angleton himself, who, in the aftermath of discovering that he had been eating out of the hand of the KGB’s most successful double agent, spent the rest of his life trying to prove that the Agency, like SIS, was being controlled by Moscow; and that its occasional successes were consequently no more than sweeteners tossed to it by the fiendish manipulators of the KGB. Angleton was wrong, but his effect on the CIA was as disastrous as if he had been right. Both services would have done much less damage to their countries, moral and financial, if they had simply been disbanded.

I never knew either Blake or Philby, but I always had a quite particular dislike for Philby, and an unnatural sympathy for Blake. The reasons, I fear, have much to do with the inverted snobbery of my class and generation. I disliked Philby because he had so many of my attributes. He was public-school educated, the son of a wayward and dictatorial father—the explorer and adventurer, St. John Philby—he drew people easily to him and he was adept at hiding his feelings, in particular, his seething distaste for the bigotries and prejudices of the English ruling classes. I’m afraid that all of these characteristics have at one time or another been mine. I felt I understood him too well, and in some odd way he seems to have sensed this, for in his last interview before he died he told his interviewer, Phil Knightley, that he had the feeling I knew something discreditable about him. And in a way, he was right: I knew what it was like, as he did, to be brought up by a man so oversized that your only resort as his child was to subterfuge and deceit. And I knew, or thought I knew, how easily the anger and inwardness thus born could turn themselves into a love-hate relationship with the father images of society, and finally with society itself, so that the childish avenger becomes the adult predator, a thing I touched upon in my most autobiographical novel,

A Perfect Spy.

I knew, if you like, that Philby had taken a road that was dangerously open to myself, though I had resisted it. I knew that he represented one of the—thank God, unrealised—possibilities of my nature.