Titanic (22 page)

Authors: Deborah Hopkinson

(Preceding image)

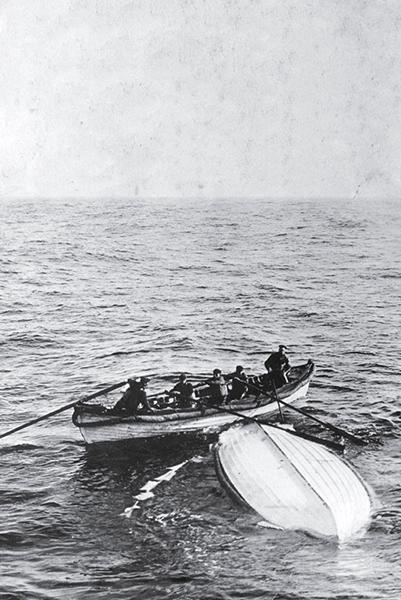

A photograph showing Collapsible B, which washed off the deck of the

Titanic

upside down. Seventeen-year-old Jack Thayer and others endured a tense night standing on the bottom of this boat.

“ . . . the boat we were in started to take in water. . . . We had to bail. I was standing in ice cold water up to the top of my boots all the time, rowing continuously for nearly five hours. . . .”

— Marian Thayer (Jack Thayer’s mother)

At 3 a.m. in the North Atlantic it was dark and terribly lonely.

The moonless sky was peppered with brilliant stars. But the immense canopy above only reminded the shocked survivors of how small and vulnerable they were.

Their beautiful ship, a symbol of human achievement, workmanship, and technology, was gone. They were alone in their tiny boats on a great sea.

Twenty lifeboats drifted, one upside down.

A little more than 700 people were now in lifeboats; they were all that remained of the 2,208 passengers and crew. All the excitement and anticipation of the

Titanic

’s maiden voyage had turned to shock and sorrow.

Earlier that night, passengers had been enjoying dinner, music, and conversation. For some, an Atlantic crossing was familiar, but for many this had been the journey of a lifetime, a start to a new life in America. Now many families were ripped apart forever. Some people had lost not just loved ones, but their money and possessions. All they had were the clothes they wore.

As they shivered in the freezing air, the survivors could barely absorb the tragedy that had transformed their lives. Many

were dressed lightly, unprepared for the cold. The lifeboats had few, if any, provisions — no lights, food, or even drinking water.

The disaster might have been easier to understand if there’d been a fierce storm, with pounding waves and howling winds.

But the night remained still and clear. The sea was calm. Dead calm.

Now, in the darkness of that terrible night, even those

who feared they had lost their loved ones forever couldn’t help wondering: Would help come in time to save their own lives?

From the time that Lifeboat 13 was launched, Lawrence Beesley realized that no one on board had the slightest idea what to do or where to go. If there was some sort of plan for the lifeboats, the crew members in his lifeboat certainly weren’t aware of it.

“Shouting began from one end of the boat to the other as to what we should do, where we should go . . .” he recalled. “At last we asked, ‘Who is in charge of this boat?’ but there was no reply.”

Finally everyone decided that it made sense for a crew member in the stern next to the tiller to be in charge. They also determined to try to stay as close to the other lifeboats as possible. It could be fatal to drift away.

“Our plan of action was simple: to keep all the boats together as far as possible and wait until we were picked up by other liners,” said Lawrence.

Some people had heard a rumor that the

Olympic

was already on her way and would get there by two the next afternoon. Lawrence remembered one crew member saying, “‘The sea will be covered with ships tomorrow afternoon: they will race up from all over the sea to find us.’”

But the

Olympic

was more than five hundred miles away.

Governess Elizabeth Shutes had been evacuated in Lifeboat 3, one of the first boats launched, at a point when it seemed impossible to believe that anything could happen to the great

Titanic

. In fact, she had been scared of leaving the safety of the ship.

Lifeboat 3 had no emergency supplies — no lanterns, biscuits, or fresh water. If help didn’t arrive, or they drifted too far and got lost, they wouldn’t survive long. Elizabeth didn’t have much confidence in the crew members either.

“Our men knew nothing about the position of the stars, hardly how to pull together,” Elizabeth recalled. “Two oars were soon overboard. The men’s hands were too cold to hold on. We stopped while they beat their hands and arms, then started on again.”

As the hours dragged on, Elizabeth felt her spirits sink further. “The life preservers helped to keep us warm, but the night was bitter cold, and it grew colder and colder, and just before dawn, the coldest, darkest hour of all, no help seemed possible.”

She’d never seen so many stars. But the beautiful night just seemed to make things worse, to intensify the loneliness that everyone felt. All they could do was hope and wait for dawn.

In Lifeboat 14, Charlotte Collyer clutched her eight-year-old daughter, Marjorie, to her, and tried not to think about her husband’s fate. That awful night was a blur.

“I have no idea of the passage of time. . . . Someone gave me a ship’s blanket which seemed to protect me from the bitter cold and Marjorie had the cabin blanket that I had wrapped around her, but we were sitting with our feet in several inches of icy water.”

The survivors were hungry and thirsty too. “The salt spray had made us terribly thirsty and there was no fresh water and certainly no food of any kind on the boat . . . The worst thing that happened to me was when I fell, half fainting against one of the men at the oars, my loose hair was caught in the row-locks and half of it was torn out by the roots.”

But while these survivors were cold and in shock, they were relatively safe — so long as rescue arrived soon.

That wasn’t true for the men on Collapsible B, the lifeboat that been swept into the sea upside down. Eventually twenty or more men found themselves perched precariously on its bottom, trying to stay awake, stay on, stay alive.

“We were standing, sitting, kneeling, lying, in all conceivable positions, in order to get a small hold on the half inch overlap of the boat’s planking, which was the only means of keeping ourselves from sliding off the slippery surface into that icy water,” recalled Jack Thayer. “I was kneeling. A man was kneeling on my legs with his hands on my shoulders, and in turn somebody was on him . . . we could not move.

“The assistant wireless man, Harold Bride, was lying across, in front of me with his legs in the water, and his feet jammed against the cork fender, which was about two feet under water.”

They didn’t dare move, afraid of being thrown into the sea. And it seemed to them all as if the air was leaking from under the boat, “lowering us further and further into the water.”

“We prayed and sang hymns . . . Harold Bride helped greatly to keep our hopes up . . . He said time and time again, in answer to despairing doubters, ‘The

Carpathia

is coming up as fast as she can. I gave her our position. There is no mistake. We should see her lights at about four or a little after.’”

Jack could only hope that Harold Bride was right.

Things weren’t much better on Collapsible A, which, although right side up, had been swept off the ship before its canvas sides were pulled up.

Ole Abelseth felt lucky to be on it just the same. Though he kept swinging his arms to stay warm, it was a long, grueling night. “In this little boat the canvas was not raised up. We tried to raise the canvas up but we could not get it up. We stood all night in about 12 or 14 inches of water on this thing and our feet were in the water all the time.”