Today Will Be Different (2 page)

Read Today Will Be Different Online

Authors: Maria Semple

Tags: #Family Life, #Fiction / Literary, #Literary, #Fiction / Contemporary Women, #Contemporary Women, #Fiction, #Fiction / Humorous, #General, #Fiction / Family Life, #Humorous

Yo-Yo trotting down the street, the prince of Belltown. Oh, Yo-Yo, you foolish creature with your pep and your blind devotion and your busted ear flapping with every prance. How poignant it is, the pride you take in being walked by me, your immortal beloved. If only you knew.

What a disheartening spectacle it’s been, a new month, a new condo higher than the last, each packed with blue-badged Amazon squids, every morning squirting by the thousands from their studio apartments onto my block, heads in devices, never looking up. (They work for Amazon, so you know they’re soulless. The only question, how soulless?) It makes me pine for the days when Third Ave. was just me, empty storefronts and the one tweaker yelling, “

That’s

how you spell

America!

”

Outside our building, Dennis stood by his wheelie trash can and refilled the poop-bag dispenser. “Good morning, you two.”

“Good morning, Dennis!” Instead of my usual breezing past, I stopped and looked him in the eye. “How’s your day so far?”

“Oh, can’t complain,” he said. “You?”

“Can complain, but won’t.”

Dennis chuckled.

Today, already a net gain.

I opened the front door of our apartment. At the end of the hallway: Joe face down at the table, his forehead flat on the newspaper, arms splayed with bent elbows as if under arrest.

It was a jarring image, one of pure defeat, the last thing I’d ever associate with Joe—

Thunk.

The door shut. I unclipped Yo-Yo’s harness. By the time I straightened, my stricken husband had gotten up and disappeared into his office. Whatever it was, he didn’t want to talk about it.

My attitude? Works for me!

Yo-Yo raced to his food, greyhound-style, back legs vaulting past his front. Realizing it was the same dry food that had been there before his walk, he became overwhelmed with confusion and betrayal. He took one step and stared at a spot on the floor.

Timby’s light clicked on. God bless him, up before the alarm. I went into his bathroom and found him on the step stool in his PJs.

“Morning, darling. Look at you, up and awake.”

He stopped what he was doing. “Can we have bacon?”

Timby, in the mirror, waited for me to leave. I lowered my eyes. The little Quick Draw McGraw beat my glance. He pushed something into the sink before I could see it. The unmistakable clang of lightweight plastic. The Sephora 200!

It was nobody’s fault but my own, Santa putting a makeup kit in Timby’s stocking. It’s how I’d buy myself extra time at Nordstrom, telling Timby to roam cosmetics. The girls there loved his gentle nature, his sugar-sack body, his squeaky voice. Soon enough, they were making him up. I don’t know if he liked the makeup as much as being doted on by a gaggle of blondes. On a lark, I picked up a kit the size of a paperback that unfolded and fanned out to reveal six different makeup trays (!) holding two hundred (!) shadows, glosses, blushes, and whatever-they-weres. The person who’d found a way to cram so much into so little should seriously be working for NASA. If they still have that.

“You do realize you’re not wearing makeup to school,” I told him.

“I know, Mom.” The sigh and shoulder heave right out of the Disney Channel. Again, my bad for letting it take root. After school, a jigsaw puzzle!

I emerged from Timby’s room. Yo-Yo, standing anxiously, shivered with relief upon seeing that I still existed. Knowing I’d be heading to the kitchen to make breakfast, he raced me to his food bowl. This time he deigned to eat some, one eye on me.

Joe was back and making himself tea.

“How’s things?” I asked.

“Don’t you look nice,” he said.

True to my grand scheme for the day, I’d showered and put on a dress and oxfords. If you beheld my closet, you’d see a woman of specific style. Dresses from France and Belgium, price tags ripped off before I got home because Joe would have an aneurysm, and every iteration of flat black shoe… again, no need to discuss price. Buy them? Yes. Put them on? On most days, too much energy.

“Olivia’s coming tonight,” I said with a wink, already tasting the wine flight and rigatoni at Tavolàta.

“How about she takes Timby out so we can have a little alone time?” Joe grabbed me by the waist and pulled me in as if we weren’t a couple of fifty-year-olds.

Here’s who I envy: lesbians. Why? Lesbian bed death. Apparently, after a lesbian couple’s initial flush of hot sex, they stop having it altogether. It makes perfect sense. Left to their own devices, women would stop having sex after they have children. There’s no evolutionary need for it. Our brains know it, our body knows it. Who feels sexy during the slog of motherhood, the middle-aged fat roll and the flattening butt? What woman wants anyone to see her naked, let alone fondle her breasts, squishy now like bags of cake batter, or touch her stomach, spongy like breadfruit? Who wants to pretend they’re all sexed up when the honeypot is dry?

Me, that’s who, if I don’t want to get switched out for a younger model.

“Alone time it is,” I said to Joe.

“Mom, this broke.” Timby came in with his ukulele and plonked it down on the counter. Suspiciously near the trash. “The sound’s all messed up.”

“What do you propose we do?” I asked, daring him to say,

Buy a new one.

Joe picked up the ukulele and strummed. “It’s a little out of tune, that’s all.” He began to adjust the strings.

“Hey,” I said. “Since when can you tune a ukulele?”

“I’m a man of many mysteries,” Joe said and gave the instrument a final dulcet strum.

The bacon and French toast were being wolfed, the smoothies being drunk. Timby was deep into an

Archie Double Digest

. My smile was on lockdown.

Two years ago when I was getting all martyr-y about having to make breakfast every morning, Joe said, “I pay for this circus. Can you please climb down off your cross and make breakfast without the constant sighing?”

I know what you’re going to say:

What a jerk! What a sexist thug!

But Joe had a point. Lots of women would gladly do worse for a closet full of Antwerp. From that moment on, it was service with a smile. It’s called knowing when you’ve got a weak hand.

Joe showed Timby the newspaper. “The Pinball Expo is coming back to town. Wanna go?”

“Do you think the Evel Knievel machine will still be broken?”

“Almost certainly,” Joe said.

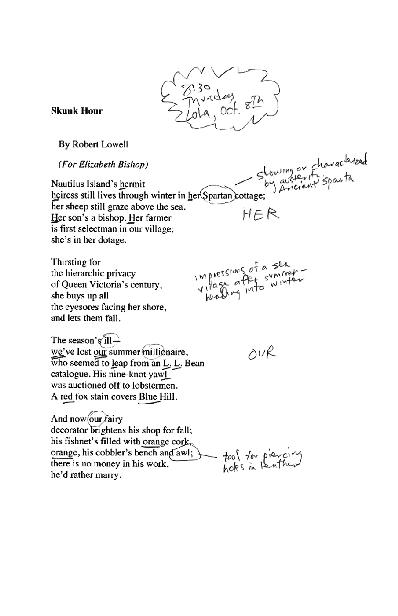

I handed over the poem I’d printed out and heavily annotated.

“Okay, who’s going to help me?” I asked.

Timby didn’t look up from his

Archie.

Joe took it. “Ooh, Robert Lowell.”

I began from memory: “‘Nautical Island’s hermit heiress still lives through winter in her Spartan cottage; her sheep still graze above the sea. Her son’s a bishop. Her farmer’s first selectman’—”

“‘Her farmer

is

first selectman,’” Joe said.

“Shoot. ‘Her farmer

is

first selectman.’”

“Mom!”

I shushed Timby and continued with eyes closed. “‘… in our village; she’s in her dotage. Thirsting for the hierarchic privacy of Queen Victoria’s century, she buys up all the eyesores facing her shore, and lets them fall. The season’s ill—we’ve lost our summer millionaire, who seemed to leap from an L. L. Bean catalogue’—”

“Mommy, look at Yo-Yo. See how his chin is sitting on his paws?”

Yo-Yo was positioned on his pink lozenge so he could watch for dropped food, his little white paws delicately crossed.

“Aww,” I said.

“Can I have your phone?” Timby asked.

“Just enjoy your pet,” I said. “This doesn’t have to turn into electronics.”

“It’s very cool what Mom is doing,” Joe said to Timby. “Always learning.”

“Learning and forgetting,” I said. “But thank you.”

He shot me an air kiss.

I pressed onward. “‘His nine-knot yawl was auctioned off to lobstermen’—”

“Don’t we love Yo-Yo?” Timby asked.

“We do.” The simple truth. Yo-Yo is the world’s cutest dog, part Boston terrier, part pug, part something else… brindle-and-white with a black patch on one eye, bat ears, smooshed face, and curlicue tail. Before the Amazon invasion, when it was just me and hookers on the street, one remarked, “It’s like if Barbie had a pit bull.”

“Daddy,” Timby said. “Don’t you love Yo-Yo?”

Joe looked at Yo-Yo and considered the question. (More evidence of Joe’s superiority: he thinks before he speaks.)

“He’s a little weird,” Joe said and returned to the poem.

Timby dropped his fork. I dropped my jaw.

“Weird?”

Timby cried.

Joe looked up. “Yeah. What?”

“Oh, Daddy! How can you say that?”

“He just sits there all day looking depressed,” Joe said. “When we come home, he doesn’t greet us at the door. When we are here, he just sleeps, waits for food to drop, or stares at the front door like he has a migraine.”

For Timby and me, there were simply no words.

“I know what he’s getting out of

us,

” Joe said. “I just don’t know what we’re getting out of

him.

”

Timby jumped out of his chair and lay across Yo-Yo, his version of a hug. “Oh, Yo-Yo!

I

love you.”

“Keep going.” Joe flicked the poem. “You’re doing great. ‘The season’s ill’…”

“‘The season’s ill,’” I said. “‘We’ve lost our summer millionaire, who seemed to leap from an L. L. Bean catalogue’—” To Timby: “You. Get ready.”

“Are we driving through or are you walking me in?”

“Driving. I have Alonzo at eight thirty.”

Our breakfast over, Yo-Yo got up from his pillow. Joe and I watched as he walked to the front door and stared at it.

“I didn’t realize I was being controversial,” Joe said. “‘The season’s ill.’”

It’s easy to tell who went to Catholic school by how they react when they drive up Queen Anne Hill and behold the Galer Street School. I didn’t, so to me it’s a stately brick building with a huge flat yard and improbably dynamite view of the Puget Sound. Joe did, so he goes white with flashbacks of nuns whacking his hands with rulers, priests threatening him with God’s wrath, and spectacle-snatching bullies roaming the halls unchecked.

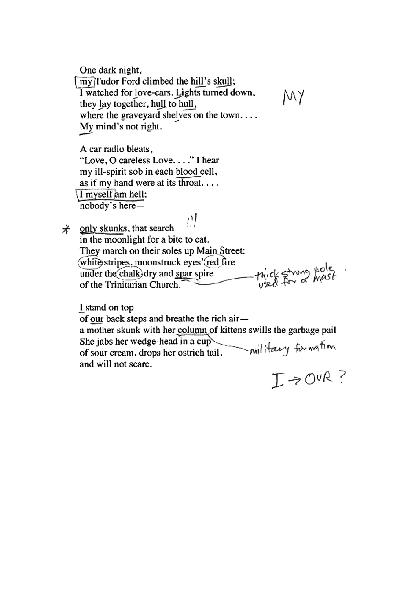

By the time we pulled into drop-off, I’d recited the poem twice perfectly and was doing it a third time for charm. “‘One dark night, my Tudor Ford climbed the hill’s skull.’ Wait, is that right?”

Ominous silence from the backseat. “Hey,” I said. “Are you even following along?”

“I am, Mom. You’re doing perfect.”

“

Perfectly

. Adverbs end in

l-y

.” Timby wasn’t in the rearview mirror. I figure-eighted it to see him hunched over something. “What are you doing?”

“Nothing.” Followed again by that high-pitched rattle of plastic.

“Hey! No makeup.”

“Then why did Santa put it in my stocking?”

I turned around but Timby’s door had opened and shut. By the time I swung back, he was bounding up the front steps. In the reflection of the school’s front door, I caught Timby’s eyelids smeared with rouge. I rolled down my window.

“You little sneak, get back here!”

The car behind me honked. Ah, well, he was the school’s problem now.

Me peeling out of Galer Street with seven child-free hours on the horizon? Cue the banjo getaway music.

“‘I myself am hell; nobody’s here—only skunks, that search in the moonlight for a bite to eat. They march on their soles up Main Street: white stripes, moonstruck eyes’ red fire under the chalk-dry and spar spire of the Trinitarian Church. I stand on top of our back steps and breathe the rich air—a mother skunk with her column of kittens swills the garbage pail. She jabs her wedge-head in a cup of sour cream, drops her ostrich tail, and will not scare.’”

I’d nailed it, syllable for syllable.

Alonzo stuck out his hand. “Congratulations.”

You know how your brain turns to mush? How it starts when you’re pregnant? You laugh, full of wonder and conspiracy, and you chide yourself, Me and my pregnancy brain! Then you give birth and your brain doesn’t return? But you’re breast-feeding, so you laugh, as if you’re a member of an exclusive club?

Me and my nursing brain!

But then you stop nursing and the terrible truth descends: Your good brain is never coming back. You’ve traded vocabulary, lucidity, and memory for motherhood. You know how you’re in the middle of a sentence and you realize at the end you’re going to need to call up a certain word and you’re worried you won’t be able to, but you’re already committed so you hurtle along and then pause because

you’ve

arrived at the end but the word hasn’t? And it’s not even a ten-dollar word you’re after, like

polemic

or

shibboleth,

but a two-dollar word, like

distinctive,

so you just end up saying

amazing?