Too Close to the Edge (27 page)

He nodded.

“You know, Paul, I was suspicious of Greta having access to Laurence’s keys. But it worked the other way around. It was Laurence who made use of Greta. He waited in the back room of Racer’s Edge for Greta to finish work. While he was there there was nothing to stop him picking up the charge card copies from that day—Greta waited until the end of the day to stuff them in the manila envelope. The day’s receipts were there, so he could get the name from the credit card and the shoe size from the receipt.”

“But why, Jill?” Connie Pereira came up beside Murakawa. She held up a bunch of tulips.

“Thanks.”

“Thank me later. Now go on about Mayer and the shoe thefts.”

“Because he realized that sooner or later the ring would get broken and the trail would lead back to Aura Summerlight. Aura’s a transient. If she’d had an hour’s notice, she’d have been gone. It was only because she was overwhelmed by Liz’s murder that she didn’t spend her four fifty getting her truck in running order and head back to Santa Fe.”

“But why would Mayer want to set her up?” Connie asked.

“To undermine Liz, and to set

her

up. He’s a bright guy. He knew we’d conclude that Aura didn’t orchestrate the thefts. Once we’d passed on her, the trail would have pointed to Liz. Maybe we’d never have gotten proof, but we would have hassled her. And even if we dropped the case for lack of evidence, the stigma would be there. The people on those city boards and committees she dealt with, they’d wonder if she really was a thief.”

“But wasn’t he afraid Aura Summerlight would have ratted on him? … Oh,” Murakawa said, as the answer occurred to him. “Who would believe her against him, huh?”

“And if she felt pressured, she would have left. He could have given her money for a plane ticket.”

Pereira nodded, knowingly. Looking down at the tulips in her hand, she said, “Let me get these in water.” She pulled the rolling bed table around. “Okay if I add them to these daffodils?”

“Sure.” I said. “Who brought those? I don’t remember anyone with them.”

“Jill, your friends have been in and out of here ever since you arrived. It’s been nearly two days since the accident. Howard didn’t even go home to sleep.”

“Are the daffodils from him?”

Connie plucked a note from the styrofoam container.

“Read,” I said.

“There’s no name. It just says ‘from a friend of a friend.’ Who’s that?”

I smiled. “A secret admirer.”

“Come on.”

“No,” I said. “You see me with unsightly bruises, with my hair matted to my head. Murakawa’s been speculating about the prognosis of bones and ligaments I didn’t know I had. I’m entitled to a few secrets.”

A nurse walked in and planted herself at the foot of the bed. Smiling at Murakawa and Pereira, she said, “So you’re back again. I’m glad she’s awake this time.” To me, she added, “You’ve got good friends here.”

“I know.”

“But I’m afraid I’m going to have to throw you two out now. It’s time to scrub her down.”

“Okay,” Pereira said, “but, Jill, make the most of this rest. You’ve got a lot of paperwork waiting when you get back to the station.”

“When do you think that’ll be?” I asked, aiming the question at the nurse.

But it was Murakawa who said, “A couple of weeks anyway. Maybe more.”

“Inspector Doyle said he’d send someone out to get your statements on both cases. You can believe they’ll be here before a couple of weeks!” Pereira added, as they left.

When I woke the next time, the light was on. The sky outside the window was darkening. Howard was sprawled in the chair next to the bed, his eyes half-closed, his chin nearly on his chest.

“Howard, how long have you been here?”

He shrugged. “I don’t know. What time is it, five? How many hours is that? But I haven’t been here all the time. I had a trap set at University and San Pablo this afternoon. Took me a month and a half to get it set.”

I smiled. My cheeks hurt. “And you thought you should be there to snap it, huh?”

“I figured you’d understand.”

I smiled again, carefully. “Yeah.”

He put his hand over mine. His jaw tightened. “You know, Jill, when that copter came down, I could see you through the glass. I don’t ever want to see something like that again.”

“I’ll try not to do it again. I’ve run the nightmare about Cousin John diving through the wave and breaking his neck so many times since the crash that it’s beginning not to terrify me. Well, not as much as it did.”

He squeezed my hand. “You were very lucky. It could have been a lot worse.”

“I know. Murakawa laid out the possibilities, graphically.” It was not a topic I wanted to pursue. “What’s the plant on the floor, the one with flowers?”

As he turned toward the wall, I could see his face relaxing. “The one the size of a Christmas tree? Someone has a lot of faith in your recovery if he thinks you’ll be able to lug out something that size.” He pushed himself up and walked over to it. “Rhododendron, the tag says. Do you want me to read the card?”

“It can only be from one person, but go ahead, read.”

“ ‘Get well soon. We’ll put your bush in the northwest corner of the yard. Don’t worry about being bored while you recover. You can help me plan the rest as soon as you get home.’ It’s signed ‘Charles Kepple.’ Wait, there’s more. ‘P.S.—The redwood burls are the right touch.’ ” Howard turned the card over. “ ‘I’m thinking of extending the path across the yard. It could end at the rhododendron. I can have the trees hauled over and cut them during the day when the neighbors won’t kick up such a fuss and …’ ” Howard grinned. “He ran out of room.”

“Oy, and I thought I was sick before. And Murakawa said I’d be home at least a couple weeks.”

Howard laughed.

“Howard, I know this man. He won’t stop with one path. He’ll cover the entire yard in burls.”

Howard laughed harder.

“Then he’ll think about a deck, maybe two. It’s a big yard. Two decks with two or three levels each, with flower boxes and a grape arbor over one, or both. Howard, the chain saw will never be still.”

Howard tried to control himself.

“The neighbors will be screaming. The beat officer will be there so often he’ll think it’s Wally’s. Howard, I can’t live like that.”

His control gave way. A laugh burst out.

“A little lapse of bedside manner, here?” I demanded.

“You’re right,” he said struggling to control himself. “What can I do for the sick lady?”

“You serious?”

“Of course.” He looked serious.

“Okay, it’s a big favor.”

“I’m a big guy. And a nice one!” he added with a grin.

“We’ll see how nice. Since you’re not using your room at your house now, will you store my stuff there? I don’t have much, if you don’t count the newspapers and catalogs. And those you can throw out. Or maybe Nancy’d like the

Sporting Dog.

It’s not one I’m likely to use.”

“Sure. Consider it hauled.” But he looked uncomfortable. “What about you?”

“I’m going to call Mr. Kepple, tell him that I’ll be convalescing on the beach and that he can keep the burls in my flat. I guarantee you, by the time you take him this rhododendron, he’ll have every inch of my flat filled with burls and saws and bags and boxes and hoses and mowers and blowers and …”

He held up a hand. “I get the idea. You don’t mind, do you, if I put some of your stuff in the attic?”

“No, but it should all go in your room.”

“Not if I have to sleep there.”

Before the accident, I might have asked him to explain that. I might have said that things between him and Nancy would look better when he got some sleep. But a glimpse of mortality doesn’t always make one a better person. I said, “The attic’s fine.”

Howard leaned forward, taking both my hands in his. “Now that we’re through discussing what I’ll do for you, let’s talk about what you’ll give me if I don’t tell anyone about Herman Ott’s daffodils.”

Susan Dunlap (b. 1943) is the author of more than twenty mystery novels and a founding member of Sisters in Crime, an organization that promotes women in the field of crime writing.

Born in New York City, Dunlap entered Bucknell University as a math major, but quickly switched to English. After earning a master’s degree in education from the University of North Carolina, she taught junior high before becoming a social worker. Her jobs took her all over the country, from Baltimore to New York and finally to Northern California, where many of her novels take place.

One night, while reading an Agatha Christie novel, Dunlap told her husband that she thought she could write mysteries. When he asked her to prove it, she accepted the challenge. Dunlap wrote in her spare time, completing six manuscripts before selling her first book,

Karma

(1981), which began a ten-book series about brash Berkeley cop Jill Smith.

After selling her second novel, Dunlap quit her job to write fulltime. While penning the Jill Smith mysteries, she also wrote three novels about utility-meter-reading amateur sleuth Vejay Haskell. In 1989, she published

Pious Deception

, the first in a series starring former medical examiner Kiernan O’Shaughnessy. To research the O’Shaughnessy and Smith series, Dunlap rode along with police officers, attended autopsies, and spent ten weeks studying the daily operations of the Berkeley Police Department.

Dunlap concluded the Smith series with

Cop Out

(1997). In 2006 she published

A Single Eye

, her first mystery featuring Darcy Lott, a Zen Buddhist stuntwoman. Her most recent novel is

No Footprints

(2012), the fifth in the Darcy Lott series.

In addition to writing, Dunlap has taught yoga and worked for a private investigator on death penalty defense cases and as a paralegal. In 1986, she helped found Sisters in Crime, an organization that supports women in the field of mystery writing. She lives and writes near San Francisco.

Dunlap and her father at the beach, probably Coney Island. ”“My happiest vacations were at the beach,” says Dunlap, “here, at the Jersey shore, at Jones Beach, and two glorious winter weeks in Florida.”

Dunlap’s grammar school graduation from Stewart School on Long Island, New York.

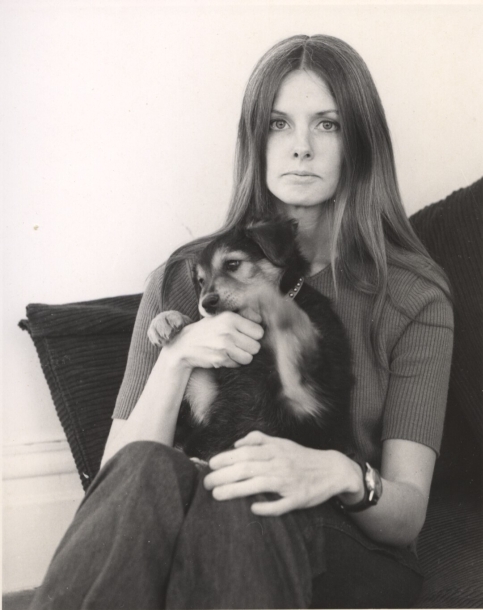

In 1968, Dunlap arrived in San Francisco; this photo was taken by her husband-to-be atop one of the city’s many hills. Dunlap recalls, “It’s winter; I’m wearing a T-shirt; I’m ecstatic!”

Dunlap’s dog Seumas at eight weeks old. “We’d had him two weeks and he was already in charge, happily biting my hand (see my grimace),” she says. “He lived for sixteen good, well-tended years.”