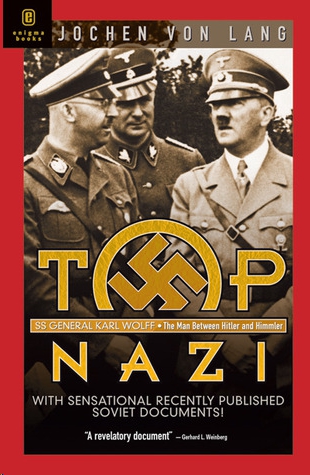

Top Nazi

Top Nazi

SS General Karl Wolff

The Man Between Hitler and Himmler

Jochen von Lang

Top Nazi

SS General Karl Wolff

The Man Between Hitler and Himmler

Enigma Books

All rights reserved under the International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Published in the United States by

Enigma Books, New York

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the written permission of Enigma Books

Translated by

MaryBeth Friedrich

Original German title:

Der Adjutant

Karl Wolff: Der Mann zwischen Hitler und Himmler

Copyright © 2013 by Enigma Books

ISBN 978-1-936274-53-6 (e-Book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lang, Jochen von.

[Adjutant.]

Top Nazi: the man between Hitler and Himmler / Jochen von Lang.

p. : ill. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

“Translated by MaryBeth Friedrich”—T.p. verso.

1. Wolff, Karl, 1900–1984.2. Nazis—Biography.3. Germany—Politics and government—1933–1945.4. World War, 1939–1945—Germany.I. Friedrich, MaryBeth.II. Title.III. Title: Adjutant.

DD247.W59 L36 2005

943.086/092 B

Table of Contents

1

.

“Where Did You Serve?”

2

.

GOT: The Source of Life

3

.

In the Good Graces of the Führer

4

.

Kristallnacht: The Night of Broken Glass

5

.

Megalomania as National Illness

6

.

“…and tomorrow the entire world!”

7

.

The Messiah for the Next 2000 years

8

.

“Even the Guard Must Obey”

9

.

“Take Over the Vatican!”

10

.

The Pope and the Anti-Christ

11

.

“When everyone betrays…”

12

.

Caught in the Middle

13

.

Cooperation Has Its Price

14

.

Prisoner at Nuremberg

15

.

The “General” Representative

16

.

Eichmann’s Accomplice

17

.

An Enigmatic Personality

THE DECEASED didn’t want it any other way: a black pillow covered with medals and mementoes from an inglorious age. According to the obituary, retired General Karl Wolff was buried in Prien am Chiemsee in the middle of July 1984. The usual comment regarding the specific branch of the service was missing after his name. Was this because it would have touched on the most sensitive chapter of his life? The advertising agent and retired lieutenant was in the NSDAP (the Nazi party) and joined the SS in the fall of 1931. He was part of the Black Guard of German Fascism and within a decade rose to the rank of lieutenant. Then general of the SS and general of the Waffen SS, finally becoming Heinrich Himmler’s right-hand man and a close confidante of Adolf Hitler. Although there are absolutely no supporting documents, people believe his statement that on April 20, 1945, shortly before the collapse of the Third Reich, he even reached the rank of general and senior general of the Waffen SS. He could not rise any higher.

From early youth, he consistently wanted to go above and beyond, and once he succeeded he credited it to the virtues the Germans had always claimed: diligence, honesty, obedience, and loyalty. Beyond that, he possessed innumerable tactical skills, the talent to persuade people, and sharp elbows. He certainly would have made his way in business, but with his love of the military, he was cut out for pseudomilitary party management. At the time of his death, many newspapers wrote that at

the end, Karl Wolff was the highest ranking among Hitler’s surviving followers, not counting the life prisoners at Spandau Prison, the Führer’s former deputy, Rudolf Hess.

Had he been alive, Wolff would have been flattered. In truth, he was one of the unknown giants of Hitler’s Reich who worked in the shadows. Only the top five hundred in the party and state knew his name and his functions. Of course, he too wanted to be in the limelight, but there were other higher-ranking “state actors” nudging and shoving. He wore a uniform well decorated with tinsel, but that was common at that time. He was not an actor in public; he worked through conversations, orders and written material. Granted, he was the representative of his city in the Reichstag, but in that make-believe parliament only one player was allowed to shine. Wolff’s job was to cheer him on, vote “Yes,” as ordered, and sing when the national anthem was played. After events the newspapers sometimes mentioned his name on the special list of honored guests as a constant escort of the Reichsführer SS, but he was only one of many.

At the beginning of the war, Wolff worked as Himmler’s eyes and ears at the Führer’s headquarters. What he did there would not make him popular. He either performed decorative service or was busy with secret information, which Germans only found out about after the war. When he occasionally allowed himself to stray from the party line by helping those in distress, he desperately needed to remain hidden. Only on one occasion did General Wolff take the opportunity to make himself known in public to the whole world, when he and the last intact German army surrendered to the Allied forces in Italy shortly before the end of the war, thereby shortening the Second World War in the south by several days. Whatever moved him to this action shall be assessed by history. The Germans hardly noticed it, as they were busy surviving in the Reich, which at that time was almost entirely occupied by the enemy.

The surrender in the south has already been described and critically evaluated in many books. Therefore, it may no longer illustrate the life and work of General Karl Wolff. Even his death at 84 was at best an occasion for obituaries in the press. On the day of his death, this biography had already been written, except for the final chapter. With its many details, it can serve as a contribution to contemporary history. Wolff was often a witness to historical events. He discussed fragments of these stories in unpublished manuscripts or on tape, preferring scenes where he could portray himself as the center of attention. If one compares his presentations to the relevant documents the latter often prove to be

embellished. Rather than making contributions to German history, he provided anecdotes. Himmler is one of the few National Socialists whom Wolff described with conflicting emotions. Hitler seems agreeable, understanding and sometimes statesmanlike and strict. Wolff himself is, and remains, the idealist in this environment, someone who always wants what’s good. Since he portrays himself as someone who never thought or planned any misdeeds, he remained unscathed by the monumental crimes that were committed by those around him. If someone were to prove to him that he could not have missed knowing about these crimes and that he even played a part in them, he explained with carefully measured words why he could, and even had to, view what was happening as legal. The blue-eyed Parsifal fell very early for the sirens of power in Hitler’s magic garden.

Even if he never wanted to admit it, he was also affected by the amorality of the Nazi system. His middle-class respectability disintegrated due to the sick complex whose symptoms of moral and spiritual depravity can be summed up as the Nazi Syndrome. To counter this particular illness, one must study its extreme symptoms as they appear in General Wolff. From the beginning, he was one of those in whom Hitler had placed his hopes, just as, on the other hand, the mass charmer in the brown shirt provided a message of salvation, which could only make the high school graduate, former lieutenant, bank employee, and small business entrepreneur a true believer. When the Führer promised he would free Germany from disgrace and want, Wolff, a member of the upper middle class, saw in Hitler the savior from the threatening problem of doing away with classes. When Hitler announced that the soldier at the front as well as the officer would once again receive special honors, Wolff saw his opportunity for personal advancement. When Germany became rich and powerful once again, Wolff would also be allotted more power and wealth. Hitler’s promise that in his Reich only those with “German blood” should receive honors, jobs, and dignity, and that the leadership would be filled with Germans of the Nordic-Germanic race, he strengthened the blond warrior in his certainty of belonging to the nation’s elite.

His curriculum vitae shows how strong the temptation was, especially for him, to march in the “Brown Battalion” singing the Horst-Wessel. It is clear why so few of those marching found the strength to turn around. It also explains why so many closed their eyes when terrible things were happening and why they eased their consciences by saying, “Things get dirty when work is being done.”

General Wolff received the biography he wanted so much only posthumously and it turned out differently from the way he had wanted for thirty years to write it. Had he been able to do so, it would tell the German people what he had done for them and what he had to put up with for them. Instead, they now learn that he was typical of his generation, a man who always considered himself a patriot cannot therefore deny this service to his country, even after his death.

Jochen von Lang

I

n September 1964 a jury in Munich sentenced Karl Wolff, the former general of the SS and general of the Waffen SS, to fifteen years in prison. He was found guilty of having participated in the murder of 300,000 Jews by arranging for railway transport cars in which the victims were taken from the Warsaw ghetto to the gas chambers at the extermination camps. Five years after the sentence, Wolff was released because the court-appointed doctors declared him unfit to remain in prison due to his poor health. From then on he lived in Darmstadt, Munich, or Prien am Chiemsee when he wasn’t traveling. His travels took him as far as South America. He never stopped protesting that he had been sentenced unfairly because he had only found out shortly before the end of the war that the Jews had been killed. The court did not believe him. For almost a decade he had been one of the closest confidantes of Heinrich Himmler, the Reichsführer SS, Hitler’s highest ranking police officer and master of all the concentration camps. Himmler called him “Wolffie.” At the very least, however, he must have discovered what was really happening to the Jews during his service for Hitler and Himmler at the Führer’s headquarters between 1939 and 1943.

On the other hand, as the highest commander of the SS and police in Italy, and also as the authorized representative general of the German Armed Forces in Italy, SS General Karl Wolff played a considerable part in the capitulation of Army Group South of the German Armed Forces to American and British forces on May 2, 1945. Thanks to this action, the war on the German southern front ended six days prior to the general ceasefire in Europe. Under Hitler’s state law (still operative at the time), capitulation was treason, punishable only by death. In some towns of the southern Tyrol Wolff enjoyed being celebrated from time to time for saving that region from war and destruction. By ending the war early, Wolff further asserted that he had spared German and Allied soldiers six full days and nights of fighting and, therefore, many casualties.

As with several of Wolff’s contemporaries, even his own feelings fluctuated, torn between approval and hatred of the Nazi party. He contributed to this himself. Whenever the responsibility for the crimes of the Third Reich was raised, he professed not to know, not being involved, or at the very least as a powerless opponent.

Anyone seeking the answer to the question of why the Germans fell under the spell of the crafty agitator Adolf Hitler and his mesmerizing swastika over half a century ago, and why they remained true to him to the bitter end, will find the equally vivid and universal explanation of this phenomenon concentrated in the person, and the rise and fall, of SS officer Karl Wolff. He would have loved to have been, like the vast majority of people, an excellent German, but his career came to a forced ending in the general catastrophe. And so he turned into a metaphor of an era in German history, an example of his generation, although not by choice.