Tori Amos: Piece by Piece (25 page)

Read Tori Amos: Piece by Piece Online

Authors: Tori Amos,Ann Powers

FOR TORI'S MOM, MARY ELLEN COPELAND AMOS

the Kindest eyes

are waving

from the farthest reach

of the Disembarkment

gate.

a Small hand

that for 75 Octobers

has touched the

Canadian Sunset–colored leaves

of the maple tree

reaching reaching

above the heads

staying till

Time's last moment of breath

Flight BA293

is Boarding

and I'm leaving

the Kindest smile.

the things I said at

good god.

is he good?

he's a hussy.

But she put away

the Tomahawk

the Feather

the Sage

for Candleland

and

Liturgy

and Lost

her Native fire

only for a while.

She remembered

as we all will

the call

of the Ancestors,

“2012.”

She bathed me

and held me

at my ugliest

at my smelliest

at my meanest at 18

when you think

you have the right

to punish the one

with the Kindest eyes …

for the men who couldn't see mine

and I'm racing against time now

the Kindest eyes are smiling—is it too late

to memorize her essence

yes it is

I missed that chance.

the Kindest eyes had said, “My angel, dance,

this is not goodbye,

look in the mirror

to find the Kindest Eyes.”

She is Black.

She is White.

She is Sex.

She is Death.

I watch Jimi.

I am 5.

I watch Jim.

I watch the Board of Trustees at the church shake their heads—

“No.

No way.

Not our daughters, nor our sons will be going to see

Jimi, Jim, or Jimmy.”

Fathers hurling out Biblical sound bites, from

“in Sin you were born”

to

“Gird your Loins.”

I think to myself—

Okay gentlemen, put those loins on the grill, honeylamb.

Medium rare.

A portion.

A part.

The loin of the Messianic Christ is awakening through these men,

Jimi, Jim, and Jimmy,

to name a few.

I hear the call.

Faint, but the trumpet is blaring.

As voices try and drown out Jimi's axe,

all the while the gnosis of the serpent is stirring his Strat.

Upside down.

Left handed.

The pickup switch in his control.

And the wind cried Mary.

And I heard the cry—

in the halls of the Peabody

In the practice rooms—

some of the most accomplished players of

She who is Black,

She who is White—

play Liszt, Chopin, and then of course there was always Prokofiev.

I wanted him.

I was seven.

Not to play his piece,

Concerto in C-sharp Minor

, something I would study one day,

but I wanted the mind.

The mind that could finger that piece.

But in the rests of

L'Après-midi dun Faune

by my Spirit Brother, Debussy,

and in the time changes and key signatures of my guide, Bartók— I heard the cry … She is Risen. She is Black. She is White. Good night, sweet Prince. Good night, Stratocaster.

Good night, Les Paul.

Good night, Telecaster.

Good night, Martin.

Good night, Santa Cruz.

I will study you, I will take you in.

Through my skin to my hands.

Thank you.

I have found her.

She is Risen.

She is Bösendorfer.

ANN:

If any god has a right to call in sick to the rock-and-roll pantheon, Dionysus is the one. This Greek sacrificial figure, whose festivals defined old-fashioned frenzy, is invoked so of en in the context of contemporary music that his dancing shoes must be worn right through. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and composers like Richard Strauss conjured his spirit in the service of modern ritual long before kick drums and power chords set the kids on fire, but Dionysus got really busy once the counterculture made rock not just a musical style but a way of life. An idol was needed to embody the strange magic that pulsed through rock performers and fans and led people to transform their appearance, their leisure time, and even sometimes their entire worldview. Dionysus, sexiest of the Western deities, fit the bill. Jim Morrison invoked him by name; many other stars earned comparison to him simply because of their genius for rebellion and the fine art of losing control. Rockers who've never heard of Persephone and Demeter, much less Sekhmet and Saraswati, fancy themselves Dionysus's followers. Yet few really bother to consider what taking on that path really entails.

Preserving the spirit of Dionysus, the wandering bringer of intoxication, allows those who dare the chance to constantly reimagine ways to break free of

rules and even ego itself. The ancient Bacchic rites that honored him may really have involved no more than some wild dancing and gnawing on raw meat, but over the centuries they have come to represent a serious step outside society, where art's ecstatic power, not morality, determines our actions. Dionysus, ideally, frees us from all assumptions, most of all those about sexuality. Yet it seems no coincidence that the most vibrant survivor from the Greek pantheon is male. Androgynous, yes, and propped up by a cult of women, but especially as he survives in rock stars’ hearts, Dionysus is a quintessential bad boy, indulging all his impulses and leaving wreckage in his wake.

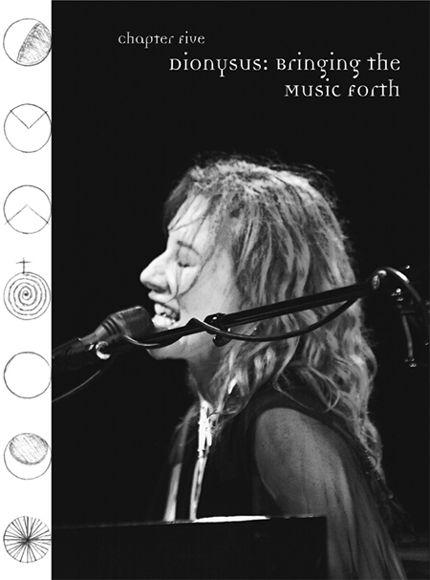

What would happen if Dionysus got back in touch with his ancient feminine side? This is what Tori Amos explores in her live performances. The scene is still bloody, but this is the blood of the god's perennial rebirth, not his dismemberment. Becoming possessed by the music that has given shape to her songs, Amos does not sacrifice either mastery or understanding. The power of rhythm intertwines with the pull of melody to reshape her. Yet she acts as neither sacrifice nor mere reveler. She becomes oracle, that feminine voice through which the stories of all time take shape.

Undulating. The rhythm—the Bösendorfer, into my body. The Kundalini has a snapdragon tonight at the base of my spine. We are playing outside. It's over a hundred degrees. Last night, Navajo women came backstage in Phoenix and smoked their Hozho Natooh with us—this sacred tobacco was lovingly picked by their grandmother. As the Dineh (Navajo) woman from the tobacco clan talked with me, she rolled the sacred tobacco in a husk of corn and began her chant, her prayer. First she spoke of things that were personal to me, then she began her weaving of song in her ancient language. I received this blessing with the feeling that I myself had been retuned (like the pianos) to be played by this land. This particular

land that was so much a part of the songs “a sorta fairytale,” “Crazy,” “your cloud,” “Indian Summer,” and the historical tragedy of “wampum prayer.”

Matt and Jon then came along with Chelsea, Ali, and Dunc to receive their message. When we all gathered in a circle in the end, as she sang in her clan's language, Tash demanded in and came to stand before this medicine woman. I held my breath as the two of them seemed to understand each other completely, one a two-and-a-half-year-old and one a woman chanting in Dineh. As the smoke surrounded Tash, I held my breath but did not interrupt as she began to move her small body in rhythm. It was almost as if a hand held me firmly back. The Dineh woman wrapped the smoke (which I thought looked like seven circles of smoke) quickly around Tash. I thought of the “seed of life” Mandala, which is an ancient shape made up of six circles with the seventh circle having been created out of the interconnectivity of the six. Sacred geometry. I felt Poppa's presence. I then realized that Tash had chosen her own Baptism. It was her soul that did this. She had not been included by me originally, but she herself chose to be included as we sat in the circle holding hands. We surrounded her as she sat enveloped in the Hozho Natooh and the Dineh song. In the song “Ruby through the Looking-Glass,” I talk about being “Baptized of fire and every beat in the bar.” Well, Tash really has been, but by a loving fire; she was also Baptized through song, through the song of the Dineh's true mother, Changing Woman, creatrix of the Dineh (the people) and the seasons.

That was last night. Tonight we are in the basin of Cochise's Holy Mountain. I feel his presence watching over everything I can see. We are in Tucson. Twenty minutes before showtime, I pass Husband in the hallway backstage. I stare at him. He stares at me. He laughs. I hear an underlying warning in that laugh. And a slight nervousness. “Take care of

my wife.” “Your wife's fine—she's on a long coffee break.” We both know she's far away. He knows I'll let her come back. But not now.

CANVAS:

“wampum prayer”

An electrical surge shoots through my body. I'm straddling what is most easily described as a pack of wild horses. Stampeding. I am racing. I am still. I am a vessel and I must “ground” this fast. I kneel. In the dark. Sage burning. I call on the four directions and ask them what essence they are bringing with them. I call it forth and ask them to help me hold this within as well as without. My vessel then begins to expand to where each direction begins to pull me. I see this in my mind's eye. The pianos have been anointed with the oils prepared specifically for tonight's journey Tonight is centered around the true events of

wampum prayer—

we are in her place of historical occurrence where mostly women and children of Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache were forced to march to Bosque Redondo, near Fort Sumner, and cruelly many were killed in the walk. Soon the Navajo (the Dineh) were rounded up, hunted down, and forced to march what they call today the “Long Walk” to Bosque Redondo (akin to the Cherokees’ fateful Trail of Tears, which occurred earlier, in 1838). I hear the chanting of Cochise's holy men and women, singing to heal the screams and cries of the hundred innocent Aravaipa Apache who were massacred not far from where we are playing tonight. I hear the old Apache woman, who woke me more than a year ago in the far reaches of Cornwall, her voice pulling me out of my bed in what is known to all of us as that “dark before dawn,” tearfully singing what became “wampum prayer”—which has begun our invocation every night, day in and day out, for the past many, many months. And here we are— here I am—point of place. The real place where the real events occurred.

I visualize a chord. A simple chord. This silverish-looking rope extends down from what I imagine as Source through the instruments, through us the players—the keepers of the tone on this particular stage, and down into the earth. This is my definition of being grounded— when you're straddling a pack of wild horses. The drums begin; they pull me to them. The revving of the engines has begun. It is showtime.

ANN:

On any given night, Amos and her companions on and behind the stage must find the balance that allows them to merge within the larger organism of the music. Amos may claim the focus of the crowd, but she cannot play star as much as humble servant. Practicing the Dionysian loss of self as an artistic and spiritual discipline, Amos must resist the cliché of self-indulgence in order to gain access to the older gift of artistic clairvoyance.

When I walk out there and hold these songs, I have to become a living library. I have to become an artist that can contain these stories and these shapes for people to walk into. I can pull these songs in and hold the structure, for example, of the sacred prostitute. I work with this archetype a lot, and she joins me when I perform the live version of “Father Lucifer,” which I developed in depth on the

Scarlet's Walk

tour. Once I explained to Matt and Jon what I was trying to achieve, we stripped the song back and created a different rhythm track in order to create the right mood for this gal. When I step into this particular archetype and hold that energy, I have to believe that I can achieve what these scarlet women, these sacred prostitutes, achieved all those years ago, but not as Mark's wife and not as the girl my friends know me as. You have to be clear on this when you are working with archetypes—which piece of them is moving through you,

so when you walk offstage you really do kind of need to know what part is them, what part is you, and which part of them you want to take back on the bus with you. And quite honestly, if Husband is on the bus that night, I might just take this gal back with me.