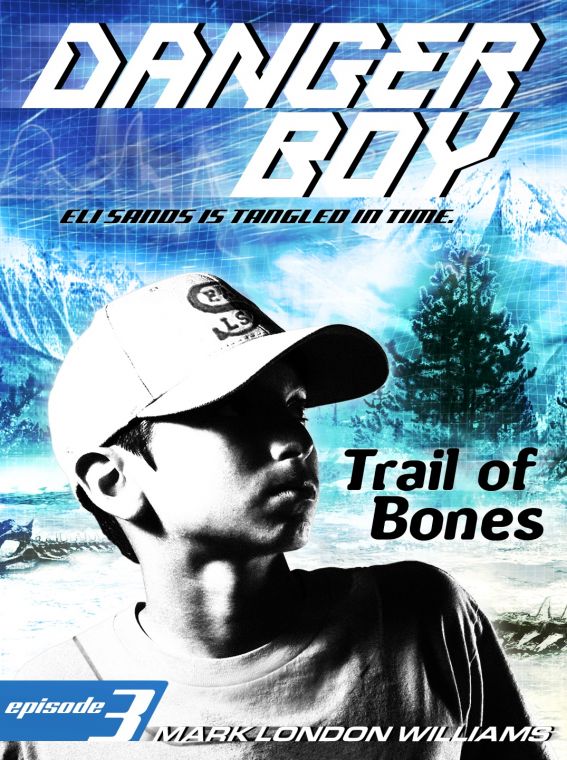

Trail of Bones

Authors: Mark London Williams

DANGER BOY

Trail of Bones

Mark London Williams

Danger Boy: Trail of Bones

By Mark London Williams

Copyright 2005 Mark London Williams

All Rights Reserved

Smashwords Edition

Candlewick Press Edition 2005

Cover by Michael Koelsch

This one’s for Becky and Caitlin,

the earliest members of my own

“Corps of Discovery.”

Prologue

January 1805

They shake the boy, call his name.

“

Eli!

Eli!” They can’t tell yet if he’s still alive.

The boy is poked, and prodded. When his eyes open a

little, there’s a surge of relief. The boy was dreaming of lying in

a sunny field, of waking to warmth and friendship. If the search

party hadn’t come along, perhaps he’d keep dreaming forever, lying

in the field of snow, where his rescuers found him.

The search party is made up of explorers, U.S. Army

captains, a shaman from a local Indian tribe — journeyers of every

sort. Including a young Indian woman — not really all that much

older than the boy — named Sacagawea.

Sacagawea is married to a fur trapper, and has

wandered around the plains and mountains a lot, and she’s pretty

sure her wandering days aren’t over yet. She’s been across plains,

and over mountains, and has always come through okay.

She considers herself pretty lucky.

She wonders if this young man considers himself

pretty lucky. He must. What else would he be doing out here by

himself?

She knows the reasons they gave at the fort, when

they were heading out to look for him: That he’d headed out for the

Spirit Mound — a hill that was supposed to be haunted not only by

spirits and phantoms, but lately, by a lizard who walked upright

like a man. And even talked.

Those were the whispered stories.

And the boy was trying to get there, alone, on foot,

the whispers went, to reach the lizard man. It was said they had

some kind of connection.

Sacagawea feels a small, growing connection to this

young man, this Eli, since she was the first to find him.

She was good at reading signs, good at picking up

trails. When she heard there was a search party heading out, she

insisted on being part of it. Her husband, the fur trapper, always

more cautious than she, tried to forbid her from going. She was,

after all, thick with child, ready to give birth very soon. And for

a lot of men in her place and time, a pregnant woman wasn’t good

luck at all — just the opposite.

But her fur trapper husband also knew she was a

better tracker than he was, so when word came that the boy had left

on his own, with another snow storm coming, and she insisted on

going, the forbiddance only lasted a few minutes.

He was worried about the baby, but then again, how

long would she really be gone? How far could the boy have

gotten?

Pretty far, as it turned out.

He’d put together a direction from the Spirit Mound

stories — many from the same young shaman who now helped look for

him — and struck out to see his friend. For his part, the fur

trapper agreed with most of the exploring party that stories about

the walking, talking lizard man were nonsense. How could such a

creature exist?

But Sacagawea kept an open mind.

She’d seen the boy around the fort, overheard his

conversations a lot, and liked him. He seemed to be like she was,

an outsider, a person from somewhere else, who found himself on a

journey not of his own making, but who was a good traveler,

anyway.

“

Wake up,” she said in her own tongue, to the

near-frozen boy, as everyone stood around, watching his eyelids

flutter, and his unfocused eyes trying to make sense of where he

was. “Come back to us.”

Instead, the boy closed his eyes again, and dreamt

of the sunny field.

Perhaps the same sunny field where President

Jefferson and the others found him, last spring.

“

We found you now,” the Indian woman tells the

boy. “You can come back to this world. You will be all

right.”

“

Sacagawea?” The others stand around her, near

where she found the boy, nestled by the crook of a storm-shattered

tree. “Is he all right?”

It’s the one named Lewis, who’s asking her. His

partner, Clark, the co-leader of the explorers, stayed behind at

the fort. Lewis shakes Eli a little, and gets a smile, but it’s a

bit of a vacant smile, and the boy still doesn’t quite wake up.

Sacagawea knows what it’s like to be in one place,

and dream of another.

She dreams of her own home, with her tribe the

Shoshones. Dreams of the time before she was kidnapped as a girl,

then sold to other tribes, or, in the case of her husband,

Charbonneau, other men.

Lately, she’s had this strong feeling that she might

be seeing her home again, for the first time in years.

Perhaps all the boy really wanted was to go

home.

“

E — li?” she says, trying his name out

loud.

Her hand closed around the stone she wore next to

her skin — the one that her brother, the chief’s son, had given her

the day she was taken. A stone that was supposed to passed along

from chief to chief, a talisman she now wore for luck, and

protection.

She’d had the rock with her ever since, on all her

journeys. She knew the boy’s journey wasn’t supposed to end yet. He

wasn’t supposed to stay asleep in the snow.

“

Come on, Eli!” Another man from the fort. Named

Gass.

“

Stay. Here.” And North Wind Comes, the

shaman-to-be from the Mandan people, neighbors of the very Hidatsas

who sold her to Charbonneau. When you’ve been captured and sold,

you know a little about the world. The stone — the jagged crystal —

has warmed her, kept her steady through all the twists and turns.

Sacagawea reaches for it now, under the folds of the skins and furs

she wears.

She clasps it, then lifts the leather strap from

around her neck.

Then she presses the stone into the boy’s hands. His

fingers are really cold, almost too cold to move, but she gets them

to shut around the stone, too, and puts her own hands around

his.

“

Sacagawea, we need to get him back.” It’s

Charbonneau, talking to her in that slightly alarmed way he has

around her, especially when she’s following her own

decisions.

“

Wait,” she says, to all of them, again speaking

in the Shoshone she hasn’t used in far too long.

For a moment, it seems the boy might fall asleep

again, and Sacagawea knows that would be bad, to let him return to

slumber in the cold like this. Even dreaming of sunny fields

wouldn’t help.

But this time his eyelids stay open and the eyes

beneath them glisten, and come into focus at last.

“

Th-th-thank you,” he says at last, through

chattering teeth, the warmth coming now not from his dreams, but

from the rock in his hand.

Sacagawea gives him a little smile, then nods.

The boy will be all right.

She feels a little kick inside her stomach.

There are other journeys yet to come. For all of

them.

Chapter One

Eli: Big Muddy

May 1804

“Well, he’s certainly not a giant.”

“And he ain’t no Indian, either. I don’t

think.”

“What shall we do with him, Mr.

Jefferson?”

All this talking. It makes my head hurt.

It’s like the time I fell asleep on the couch at my parents’ house

during a party, and I still remember hearing the phrase

brain

universe

as I was being picked up off the sofa and put to

bed.

I was five and I thought of colossal-sized

brains until the time I found out it was spelled “brane,” and meant

something else entirely, about the way the whole universe —and

maybe the universes around it, or next to it — are designed.

The design of my own universe used to be

better: There was no jarring time travel, no vanished parents, no

talking dinosaurs to explain.

Well, wait. Not that I want the dinosaur to

go away.

It feels sunny and bright above me…hot. And

cold and damp underneath me.

I’m sweating and I’m rolling around in mud

and my own “brain universe”— the one in my head— is aching. I think

I’m sick.

But everyone around me is still talking.

“I am not ‘Mr. Jefferson,’ while I am on

this trip, Mr. Howard. I am not ‘Mr. President.’ I am not in

charge, and I am not even officially here. Captain Lewis and

Captain Clark are in command. I am merely an interested citizen,

here to pursue a little science, and to wish them well.”

I’d better open my eyes and find out who’s

sounding like some kind of English teacher.

Not English teachers, as it turns out.

Cowboys.

Or maybe not cowboys, exactly. Daniel Boone…

sorts of guys. In scuffed buckskins and leather jackets and raccoon

caps and floppy wide hats that look almost like sombreros.

Along with a few other guys in soldier

clothes that look like they came from a production of

The

Nutcracker

, dressed in long blue coats and boots, bearing guns

with pointy bayonets.

One of those guys is taller than the others.

He’s not quite dressed like a soldier — but he still looks like

something from an old painting. With pants that don’t go all the

way down and stockings and shoes with big buckles. He has a

notebook, instead of a gun, and red hair pulled back in a little

ponytail. Hair like one of the hippies I’ve seen in the history

books.

I’d look around, but my “brain universe”

—and all the other parts of my head — feel like they weigh a

ton.

I turn my neck a little and can see some

horses and knapsacks and wooden wagons and long rifles in saddle

holsters or dangling from the arms of some of the men.

Thea and Clyne aren’t here.

I hope they made it out of the Fifth

Dimension. I hope they’re okay.

I can hear a river nearby. I guess that

explains the mud.

“Mr. Floyd! Have your men tend to the

keelboat and mind how they load the crates! We can’t afford to lose

any provisions before we’ve even begun!”

Whoever’s speaking now has dark hair and

dark eyes that you can’t see all the way into.

All these boats and provisions and guns.

Maybe it’s some kind of war party, or patrol. Or expedition.

I try to sit up again, to say something. But

my mouth feels like some of the sun and the mud are at war in

there, too. Only a gurgling sound comes out.

“Aye-aye, Cap’n Lewis, I’ll go down and give

them what for.” It’s one of the cowboy-looking men, in smelly

leather, with a stubbly beard and a kind of Civil War costume hat.

He leans in and touches my forehead. “The boy seems awful hot.”

The man takes a canteen, a leather canteen,

from around his shoulder, and pours a few drops of water on my

face.

I realize how thirsty I am.

I try to ask for more, but suddenly, I

realize what this feeling is: it’s like the moment you come out of

a dream, but aren’t fully awake, and some part of you knows you’re

not sleeping anymore, but your body isn’t ready to start taking any

orders yet, either.

Though I wonder, since I travel through time

with a talking dinosaur and a girl who’s well over a thousand years

old, if I’m even in the coming-out-of-a-dream stage at all.

“Let me see him.” A taller man with no hat,

leans over the stubble-beard guy, and stares right at me, then

opens my eye real wide with his finger and thumb.