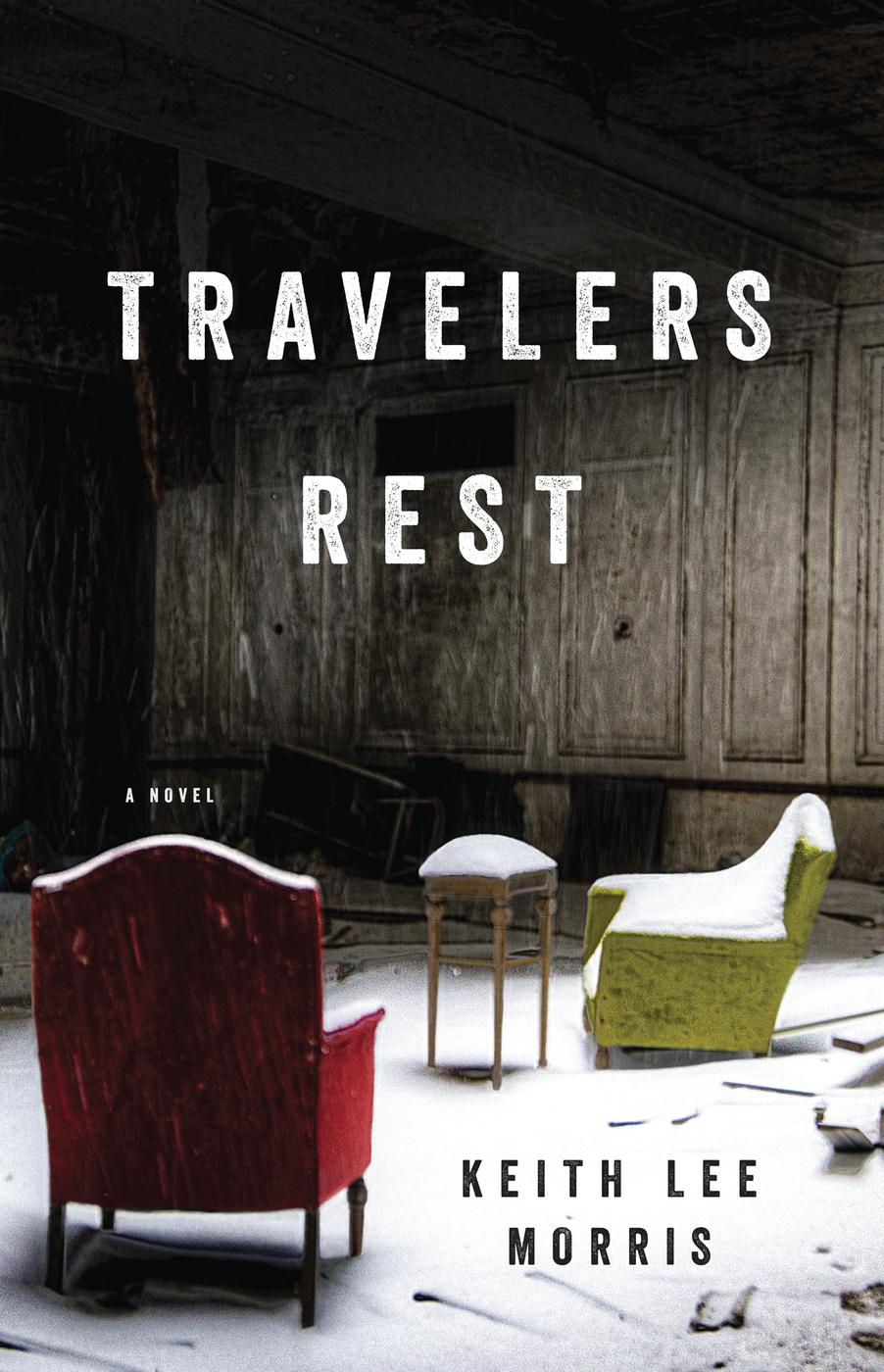

Travelers Rest

Authors: Keith Lee Morris

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author's intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author's rights.

For my mother and father, about whom I find something new to appreciate every day

A moment of the past, did I say? Was it not perhaps very much more: something that, common both to the past and to the present, is much more essential than either of them?

âMarcel Proust,

Remembrance of Things Past

Perhaps the immobility of the things that surround us is forced upon them by our conviction that they are themselves, and not anything else, and by the immobility of our conceptions of them. For it always happened that when I awoke like this, and my mind struggled in an unsuccessful attempt to discover where I was, everything would be moving round me through the darkness: things, places, years.

âMarcel Proust,

Remembrance of Things Past

I

t was snowing. The storm had started as soon as they crossed the Cascades from Seattle, and now, here in what his dad called the Idaho panhandle, Dewey looked out from the backseat at the snow sweeping over the interstate in huge white gusts, covering everything in sight. His dad held on to the steering wheel at ten and two, which meant the weather was bad. His dad had grown up in this part of the countryâwell, Seattle, anywayâbut now they lived in South Carolina and he wasn't used to driving in the snow. And it would be getting dark soon.

Uncle Robbie, who sat with Dewey in back, tried to ease the tension by showing how to play the armpit trombone, an instrument he claimed he could use to perform the song “Camptown Races” in its entirety, verses and chorus, and which he proceeded to demonstrate, sort of. It sounded like a long series of farts, and Dewey, age ten, found this highly amusing. His mother, smiling just slightly in the front seat as she looked dreamily out the window, seemed to find it somewhat amusing. His father not at all. His father never found much of anything about Uncle Robbieâwho was more than a decade younger than Dewey's father and who was coming to stay with them in Charleston for a while as part of his court-ordered rehabilitation programâamusing at all. His dad probably wished now that they'd decided to fly instead of taking the car. The plan had been to travel at a leisurely pace, get a good look at the country.

No one said anything for a while and Dewey gazed out the window. It was a pretty area, with a river running along the highway and evergreens, white with snow, covering the hills. They passed a sign, exit 70, for a town called Good Night. It seemed like a funny name for a town in Idaho. Or anyplace, for that matter.

His mother had also noticed the sign. She quit staring out the window and looked over at his dad. “Might as well be here as anywhere,” she said.

His dad opened his mouth and squinted his eyes up tight. “We're thinking of stopping?” he said. He fumbled around the console for his glasses, which he wore only when he needed to see something clearly, which he claimed wasn't often. He put the glasses on and leaned in toward the windshield and looked at the sky. “I don't guess this is going to get better anytime soon,” he said.

“It's fine with me if we stop,” his mother said. She was the sort of person who was usually fine with things. “In fact the snow makes me nervousâI'd

rather

stop.”

Dewey knew his father well enough to understand that he was probably trying to decide whether to argue. He wouldn't want to admit to himself that he'd been forced off the road by the snow, especially after all the times he'd made fun of drivers back home who, he said, couldn't even drive in the rain. A few moments passed. A huge pickup truck roared by them in the left lane, snow spinning up from the tires. His father sighed. “All right,” he said.

They pulled off at the exit, the car sliding a little bit on the ramp, his father's knuckles ridged on the steering wheel. They turned onto a quiet, winding road with no traffic. His mom used her cell phone to find the town on the Internet. “This place sounds familiar,” she said. “Good Night, Idaho. I've heard of this place. It's not the kind of name you forget.”

His father smiled but didn't take his eyes off the road. “You always say that. You always think you've heard of someplace.”

His mother ignored him and held out her phone for Dewey and Uncle Robbie in the backseat. “Here, see? It's an old mining town,” she said. “It seems like a nice place. Look, they have a beautiful old hotel.” On the screen was the small image of an old brick building taller than any other building in the town, though that wasn't saying much, even Dewey knew. His mother showed it to his dad.

“That does seem nice,” he said.

“I'm glad we're staying,” she said. “This can be like a little adventure along the way. It'll be a good way to start off the new year.” It was January 2. Dewey had to be back at school in four days.

His father adjusted his glasses and leaned forward to squint out the windshield at the falling snow, which seemed to be coming down harder every minute. “Exactly what I was thinking,” he said, in that flat tone where you couldn't tell if he was being sarcastic.

“That's what I hate about the interstate,” his mother said. “You just drive and drive and pass right by interesting places like this one.” She turned and smiled brightly at Dewey and Robbie. “You'd never even know they were here.”

T

he sign on the outside of the old hotel identified it as the Travelers Rest. Julia Addison, advancing carefully in her slick shoes on the snowy sidewalk, holding on to her son Dewey's hand to keep from falling, paused for a moment and consideredâsomething wasn't right about the name. As punctuated, it amounted to a bland statement of factâyes, travelers rested. All people did, eventually. Maybe they had forgotten a comma and exclamation pointâit was intended to be a command: Travelers, rest! Or maybe just an apostropheâTravelers' Restâwhich she decided was the nicest way to think about it: this place

belonged

to the travelers, and offered them rest.

Dewey pulled on her hand and they went up the marble steps to the hotel entrance and she held open the door for her brother-in-law, Robbie, and her husband, Tonio, who were lugging the suitcases. She was the last to step inside the door and she was busy brushing snow off her coat sleeves and her hair when she heard a voice that brought her up sharply, made her heart beat fast. Maybe she was still out of breathâthey'd had to park the car at the bottom of a hill and walk up the town's main street to the hotel. But she heard the voice againâ“Welcome to Travelers Rest”âand again her pulse quickened.

The voice belonged to an odd-looking man with a large nose and a thick mustache who stood behind a desk to the left of the entrance, and she couldn't figure out why his voice would affect her that wayâif anything, his appearance was much more startling. His nose was so large and his mustache was so bushy that he almost had no eyes, no chin, and he wore a dusty black hat with a wide brim that seemed designed to trap the chaotic mass of brown hair curling around his ears and neckline. His clothesâa striped, tight-fitting vest over a heavy shirt worn thin at the elbows, pants of a loose, shiny material with rolled cuffs, boots that appeared to be covered in soot or ashâand his stiff gait as he moved across the room made him look as if he'd been stored in a crate of mothballs and tipped up onto his feet just moments before their arrival. She felt, more than anything, a temptation to sneeze.

While Tonio asked about a room, she got her bearings and surveyed the hotel's interior. The first impression was one of disorder. In the dim and rather dusty light of the lobby she saw ladders and toolboxes and paint cans and drop cloths and sawhorsesâclearly the place was under renovation. Maybe the hotel wasn't even open, and they wouldn't be staying here after all. That would be disappointing. Why? She studied the room more closely. An enormous fireplace that, if it had contained a roaring fire, would have dispelled every shred of the hotel's gloom. Beautiful old gas lamps on the walls, tasteful (although awfully faded) wallpaper, elaborate moldings in the corners of the room, a high ceiling with a breathtaking chandelier that spanned almost half the lobby, a grand wooden staircase ascending to a second-floor landing, solid overstuffed chairs (Dewey was sitting in one of them and wiping dust from the arm), a huge circular ottoman directly beneath the chandelier. It must have been a stunningly opulent place at one timeâwhat could it possibly be doing in this little town? Who would have built a hotel like this here? She hadn't spent much time in fancy hotels, but she had a sharply tuned aesthetic sense, and that sense told her now that she was in a remarkable place, or at least a place that had once been remarkable.

She stood gazing out the front windows at the snow flying past outside. Tonio was still talking, going on in the slightly nasal voice that he used when he lectured his anthropology students. She didn't pay any attention to what he was saying. Robbie had discovered, of all things, a monocle lying around somewhere. He placed it over his right eye and marched around the room with a military air, his hands clasped behind his back, a stern expression on his face, as if he were considering weighty matters. He bumped into the furniture, staged pratfalls over the armchairs and end tables. Dewey, of course, found this wildly entertaining. She stood looking out the windows.

And then she had a funny feeling. Her mind felt white with snow, cold and pleasantly numb, and something began to form behind her visionânot exactly a memory, not exactly a dream. From somewhere she heard voices and music, lilting strings, a waltz rhythm. She had the feeling that if she turned around she would have already known exactly what was behind her, the ballroom, the dancers, the string quartet, the strange man peering out of his little eyes at the proceedings, twirling the ends of his mustache. The hotel must be hosting some gala event, some elaborate banquet from bygone days, something she never could have expected when she chose to stop here, but which she seemed somehow to have anticipated, and which now she couldn't wait to see. She could almost feel herself dancing, flowing across some huge open space. She began to say something to Tonio over her shoulder and as she turnedâ¦there it was. Through a pair of stately French doors with old, warped glass panes, a massive room with a parquet floor and curtainless floor-to-ceiling windows facing onto a snowy street. It was a ballroom, it had to be. But there were no people, nobody there, as if they'd all vanished in a heartbeat. It must have been a recording, music they played over speakers hidden somewhere, but whatever it was, it had stopped. She stepped lightly toward the doors, imagined them swinging open before her, allowing her entry, and again it was as if she heard something, saw something. Was it some movie she was remembering?

Suddenly Tonio was next to her, ready to make his report. “That's the owner,” he said. “He's nuts.”

She glanced over Tonio's shoulder. There the owner stood, firm and upright, hands behind his back, a welcoming smile creasing his cheeks behind the mustache. His smile seemed intended only for her, as if the two of them understood something no one else could.

“Why?” she said. “Is the room too expensive?”

Tonio grunted. “Too

expensive?

No, the rate's plenty cheap. In fact, he seems reluctant to let me pay him at all. He won't take a credit card.”

“Then what's the problem?” she said.

“What's the

problem?

Look at this place.”

“It's amazing,” she said.

“Yeah,” he said, “as, like, an archaeological specimen, maybe. He says the storm knocked out the electricity. He can't promise there'll be any heat. The place looks like it was hit by a fucking tornado.”

She walked slowly back across the room, toward Dewey and Robbie at the front entrance. Old photographs lined the walls, one of them an image straight from her thoughts, from the vision in the back of her headâit was the lobby full of people, dressed for the ball, coat and tails, satin dresses, all smiling, all toasting the camera with glasses of champagne. In faded ink, under the photograph, it said “January, 1886, Travelers Rest.” Next to that picture was another one, an exterior shot of the burned-out husk of a hotel, and underneath it had the same caption, “January, 1886, Travelers Rest.” One of them must have been wrong.

“But he'll let us have a room,” she said.

“He'll give us a

suite,

” Tonio said. “But get thisâwe're the only guests. It's pretty weird. Don't you think Dewey would be happier if we drove on and foundâI don't knowâa Comfort Inn? There's always a Comfort Inn.”

The light in the lobby had grown even fainter. Dewey was quiet, slumped down in one of the oversized chairs. Robbie stood at the window, still wearing the monocle over his right eye. It almost looked like it belonged there.

“You go on to the Comfort Inn if you want to,” she said. “I'm staying here.”