Trick or Treatment (25 page)

Read Trick or Treatment Online

Authors: Simon Singh,Edzard Ernst M.D.

- Make sure that your chiropractor is a mixer and not a straight. It would be unwise to be treated by a chiropractic fundamentalist, namely someone who believes in subluxations, innate intelligence and the ability of spinal manipulation to cure all diseases. The terms ‘straight’ and ‘mixer’ do not generally appear on a chiropractor’s business card, so the best way to identify a straight is to ask about the range of conditions that he or she claims to treat – a straight chiropractor will offer treatments for respiratory conditions, digestive disorders, menstrual problems, ear infections, pregnancy-related conditions, infectious and parasitic conditions, dermatological diseases, acute urinary conditions and many other ailments.

- If you visit a chiropractor and the problem is not resolved within six sessions, or there is no ongoing significant improvement within six sessions, then be prepared to stop treatment and consult your doctor for advice. Chiropractors have a reputation for lengthy and expensive treatments, as demonstrated by a survey in 2006 that monitored ninety-six patients with acute neck pain. Although the patients generally reported improvements, the treatments required twenty-four visits on average, and in two cases there were more than eighty treatment sessions. It is likely that the majority of these recoveries had little to do with the chiropractic intervention, but were largely the result of time and the body’s own natural healing processes.

- Do not allow a chiropractor to become your primary healthcare provider, which might include preventative and maintenance treatments covering all health issues. In 1995, a survey showed that 90 per cent of American chiropractors considered themselves primary care providers, but they are rarely qualified to take on this role. Patients are often impressed by the fact that many chiropractors carry the title Doctor, but this does not mean that they have attended medical school. The title generally indicates Doctor of Chiropractic (DC), which merely means that a practitioner has completed a chiropractic course lasting four years.

- Avoid chiropractors who rely on unorthodox techniques for diagnosing patients, such as applied kinesiology and the E-meter, which were described earlier. Such techniques are usually employed by straight chiropractors.

- Check the reputation of your chiropractor before embarking on any treatment, because chiropractors are more likely than medical doctors to be involved in malpractice. According to a survey conducted in California in 2004, chiropractors were twice as likely as medical doctors to be the subject of disciplinary actions. Even more worrying, the incidence rate for fraud was nine times higher for chiropractors than for doctors, and the rate for sexual boundary transgressions was three times higher for chiropractors than doctors.

- Last, but not least, try conventional treatments before turning to a chiropractor for back pain. They are generally cheaper than spinal manipulation and just as likely to be effective. There are also other reasons for following the conventional route, but we will come to these later in the chapter.

The advice above is based on serious and well-founded criticisms of some elements of the chiropractic community. For example, chiropractors, particularly in America, have earned a reputation for zealously recruiting and unnecessarily treating patients. Practice-building seminars are commonplace and there are numerous publications aimed at helping chiropractors find and retain patients. In many cases the emphasis seems to be placed on economics rather than healthcare: the chiropractor Peter Fernandez is the author of a five-volume series called

Secrets of a Practice-Building Consultant

, which starts with a volume boldly titled

1,001 Ways to Attract Patients

and ends with

How to Become a Million Dollar a Year Practitioner

.

Many chiropractors are embarrassed by the zealous profiteering of their colleagues. For instance, G. Douglas Anderson, writing in

Dynamic Chiropractic

, has argued that the chiropractic movement needs a radical overhaul:

It is high time we admit there is nothing conservative, holistic or natural about endless care, creating addiction to manipulation, or making unsubstantiated, cure-all claims. On the contrary, an excellent argument can be made that the variety of tricks, techniques and claims still used by a large percentage of our profession to keep fully functional, asymptomatic people returning for care is fraudulent.

According to Joseph C. Keating, himself a chiropractor, the tendency to profiteer and mislead can be traced back to the founders of the chiropractic therapy, particularly B. J. Palmer: ‘Indeed, the profession, as a unified body politic, has never truly renounced the marketing and advertising excesses modelled by B. J. and many clinical procedures and innovations since are noteworthy for the extraordinary and unsubstantiated claims which are made for them.’ It seems that chiropractors are fond of manipulating their patients in both senses of the word.

Stephen Barrett, a US psychiatrist and medical writer, has been at the forefront of criticizing and exposing other shady aspects of chiropractic therapy. For example, he conducted a small experiment to see how four chiropractors would diagnose and deal with the same healthy patient, a twenty-nine-year-old woman:

The first diagnosed ‘atlas subluxation’ and predicted ‘paralysis in fifteen years’ if this problem was not treated. The second found many vertebrae ‘out of alignment’ and one hip ‘higher’ than the other. The third said that the woman’s neck was ‘tight’. The fourth said that misaligned vertebrae indicated the presence of ‘stomach problems’. All four recommended spinal adjustment on a regular basis, beginning with a frequency of twice a week. Three gave adjustments without warning – one of which was so forceful that it produced dizziness and a headache that lasted several hours.

Barrett’s study of chiropractors was neither exhaustive nor definitive, but his limited sampling did suggest that there is something rotten at the heart of the chiropractic profession. Chiropractors dealing with the same healthy individual could agree on neither the diagnosis nor which part of the spine was problematic – all that they could agree on was that regular chiropractic therapy was the solution. Perhaps this should not be surprising when we bear in mind that the underlying principles of chiropractic therapy, the notions of subluxations and innate intelligence, are meaningless.

In addition to all this, and even more worrying, is Barrett’s last sentence, which mentions that his undercover patient suffered ‘dizziness and a headache that lasted several hours’. This raises an important issue that we have not yet discussed, namely safety. Every medical treatment should offer the likelihood of benefit, but it will also, almost inevitably, carry a likelihood of side-effects. The key issue for patients is simple: does the likely extent of the benefit outweigh the likely extent of the adverse side-effects, and how does this risk– benefit analysis compare to other treatments? As we shall discuss below, the dangers of chiropractic therapy can be serious and in some cases life-threatening.

The dangers of chiropractic therapy

Often the first hazard encountered when visiting a chiropractor is undergoing an X-ray examination, which seems to be a routine procedure among many practitioners. A survey conducted across Europe in 1994 revealed that 64 per cent of patients received X-rays when visiting a chiropractor, and a survey of members of the American Chiropractic Association conducted in the same year suggested that 96 per cent of new patients and 80 per cent of returning patients were X-rayed. Although many chiropractic publications explicitly advise against the routine use of X-rays, these surveys reveal an almost cavalier approach to a technology that does carry a risk of causing cancer.

It is estimated that on average medical X-rays are responsible for 14 per cent of our annual exposure to radiation. Much of the remaining 86 per cent comes from natural sources such as radon gas seeping up through the ground. The increased risk of cancer due to X-rays is small, but it is not negligible. According to a paper published in the

Lancet

in 2004, roughly 700 of the 124,000 new cancer cases diagnosed each year in the UK are due to medical X-rays. Although X-rays therefore account for 0.6 per cent of new cancer cases, they continue to be used widely in medicine because they offer tremendous benefits in terms of diagnosing and monitoring patients. In other words, conventional doctors are willing to use X-rays because the benefits outweigh the potential harm, but at the same time they minimize the use of X-rays, employing them only when there is a clear reason to do so.

In contrast, chiropractors may X-ray the same patient several times a year, even though there is no clear evidence that X-rays will help the therapist treat the patient. X-rays can reveal neither the subluxations nor the innate intelligence associated with chiropractic philosophy, because they do not exist. There is no conceivable reason at all why X-raying the spine should help a straight chiropractor treat an ear infection, asthma or period pains. Most worrying of all, chiropractors generally require a full spine X-ray, which delivers a significantly higher radiation dose than most other X-ray procedures.

This raises the question of why so many chiropractors are so keen to X-ray their patients. Partly they are blindly following a corrupt methodology and a bankrupt philosophy that has been passed down through the decades, while ignoring the latest advice from experts. On top of this, it is important to remember that X-raying patients is a very lucrative part of any chiropractic business.

In addition to the risk associated with X-rays, the actual manipulation of the spine can also have negative repercussions. In 2001, a systematic review of five studies revealed that roughly half of all chiropractic patients experience temporary adverse effects, such as pain, numbness, stiffness, dizziness and headaches. These are relatively minor adverse effects, but the frequency is very high, and this has to be weighed against the limited benefit offered by chiropractic therapy.

More worryingly, patients can also suffer serious problems such as dislocations and fractures. These hazards are more likely and more dangerous for older patients, who may be suffering from osteoporosis. For instance, in 1992 the

Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics

reported the case of a seventy-two-year-old woman who visited a chiropractor complaining of back pain. She received twenty-three treatment sessions over the course of six weeks, which resulted in multiple spinal compression fractures.

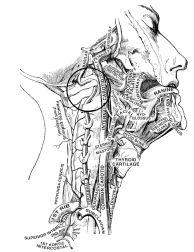

On top of all these risks, there is an even more serious hazard associated with chiropractic therapy. To appreciate this hazard, we need to refer back to Figure 5 on page 160, which shows the structure of the spine. It consists of five regions – the coccygeal region is at the base, followed by the sacral, lumbar and thoracic regions, with the cervical region at the top. The most severe risk relates to manipulation of the cervical region. There are seven vertebrae that make up this region, running from the base of the neck to the back of the skull. This is one of the most flexible parts in our body, but this flexibility comes at a cost. The region is hugely vulnerable as it carries all the lifelines between the head and the body. In particular, these vertebrae are in close proximity to the two vertebral arteries, which are threaded through pairs of holes on either side of each vertebra. This is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6

A circle shows how a vertebral artery makes a sharp kink at the final vertebra.

Before supplying oxgenrich blood to the brain, each artery takes a sharp twist because of the structure of the topmost vertebra. This kink in the arteries is perfectly natural and causes no problems, except when the neck is stretched and simultaneously turned in an extreme or sudden way. This can occur when chiropractors perform their hallmark high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust manipulation. Such an action can result in a so-called vertebral dissection, which means that the inner lining of the artery becomes torn. Vertebral dissection can affect blood flow in four ways. First, a blood clot can form around the damaged area, gradually blocking that section of the artery. Second, the clot can eventually become dislodged, be carried into the brain and block a distant part of the artery. Third, blood can become trapped between the inner and outer layers of the artery, which causes swelling, thereby also reducing the blood flow. Fourth, the injury to the artery can cause it to go into spasm; this means it contracts and effectively prevents blood flow. In all four situations, vertebral dissection can ultimately cut off the blood supply to some parts of the brain, which in turn would lead to a stroke. In the most serious cases, stroke can lead to permanent brain damage or death.