Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville (13 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

C

omparisons may be odious, but we cannot avoid them in a world that prizes excellence and yearns to know whether current pathways lead to progress or destruction. We are driven to contrast past with present and use the result to predict an uncertain future. But how can we make fair comparison since we gaze backward through the rose-colored lenses of our most powerful myth—the idea of a former golden age?

Nostalgia for an unknown past can elevate hovels to castles, dung heaps to snow-clad peaks. I had always conceived Calvary, the site of Christ’s martyrdom, as a lofty mountain, covered with foliage and located far from the hustle and bustle of Jerusalem. But I stood on its paltry peak last year. Calvary lies inside the walls of Old Jerusalem (just barely beyond the city borders of Christ’s time). The great hill is but one staircase high; its summit lies

within

the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

First published as “Entropic Homogeneity Isn’t Why No One Hits .400 Any More” in

Discover

, August 1986.

I had long read of Ragusa, the great maritime power of the medieval Adriatic. I viewed it at grand scale in my mind’s eye, a vast fleet balancing the powers of Islam and Christendom, sending forth its elite to the vanguard of the “invincible” Spanish Armada. Medieval Ragusa has survived intact—as Dubrovnik in Yugoslavia. No town (but Jerusalem) can match its charm, but I circled the battlements of its city walls in fifteen minutes. Ragusa, by modern standards, is a modest village at most.

The world is so much bigger now, so much faster, so much more complex. Must our myths of ancient heroes expire on this altar of technological progress? We might dismiss our deep-seated tendency to aggrandize older heroes as mere sentimentalism—and plainly false by the argument just presented for Calvary and Ragusa. And yet, numbers proclaim a sense of truth in our persistent image of past giants as literally outstanding. Their legitimate claims are relative, not absolute. Great cities of the past may be villages today, and Goliath would barely qualify for the NBA. But, compared with modern counterparts, our legendary heroes often soar much farther above their own contemporaries. The distance between commonplace and extraordinary has contracted dramatically in field after field.

Baseball provides my favorite examples. Few systems offer better data for a scientific problem that evokes as much interest, and sparks as much debate, as any other: the meaning of trends in history as expressed by measurable differences between past and present. This article uses baseball to address the general question of how we may compare an elusive past with a different present. How can we know whether past deeds matched or exceeded current prowess? In particular, was Moses right in his early pronouncement (Genesis 6:4): “There were giants in the earth in those days”?

Baseball has been a bastion of constancy in a tumultuously changing world, a contest waged to the same purpose and with the same basic rules for one hundred years. It has also generated an unparalleled flood of hard numbers about achievement measured every which way that human cleverness can devise. Most other systems have changed so profoundly that we cannot meaningfully mix the numbers of past and present. How can we compare the antics of Larry Bird with basketball as played before the twenty-four-second rule or, going further back, the center jump after every basket, the two-handed dribble, and finally nine-man teams tossing a lopsided ball into Dr. Naismith’s peach basket? Yet while styles of play and dimensions of ballparks have altered substantially, baseball today is the same game that “Wee Willie” Keeler and Nap Lajoie played in the 1890s. Bill James, our premier guru of baseball stats, writes that “the rules attained essentially their modern form after 1893” (when the pitching mound retreated to its current distance of sixty feet six inches). The numbers of baseball can be compared meaningfully for a century of play.

When we contrast these numbers of past and present, we encounter the well-known and curious phenomenon that inspired this article: great players of the past often stand further apart from their teammates. Consider only the principal measures of hitting and pitching: batting average and earned run average. No one has hit .400 since Ted Williams reached .406 nearly half a century ago in 1941, yet eight players exceeded .410 in the fifty years before then. Bob Gibson had an earned run average of 1.12 in 1968. Ten other pitchers have achieved a single season ERA below 1.30, but before Gibson we must go back a full fifty years to Walter Johnson’s 1.27 in 1918. Could the myths be true after all? Were the old guys really better? Are we heading toward entropic homogeneity and robotic sameness?

These past achievements seem paradoxical because we know perfectly well that all historical trends point to a near assurance that modern athletes must be better than their predecessors. Training has become an industry and obsession, an upscale profession filled with engineers of body and equipment, and a separate branch of medicine for the ills of excess zeal. Few men now make it to the majors just by tossing balls against a barn door during their youth. We live better, eat better, provide more opportunity across all social classes. Moreover, the pool of potential recruits has increased fivefold in one hundred years by simple growth of the American population.

Numbers affirm this ineluctable improvement for sports that run against the absolute standard of a clock. The Olympian powers-that-be finally allowed women to run the marathon in 1984. Joan Benoit won it in 2:24:54. In 1896, Spiridon Loues had won in just a minute under three hours; Benoit ran faster than any male Olympic champion until Emil Zatopek’s victory at 2:23:03 in 1952. Or consider two of America’s greatest swimmers of the 1920s and 1930s, men later recruited to play Tarzan (and faring far better than Mark Spitz in his abortive commercial career). Johnny Weissmuller won the one-hundred-meter freestyle in 59.0 in 1924 and 58.6 in 1928. The women’s record then stood at 1:12.4 and 1:11.0, but Jane had bested Tarzan by 1972 and the women’s record has now been lowered to 54.79. Weissmuller also won the four-hundred-meter freestyle in 5:04.2 in 1924, but Buster Crabbe had cut off more than fifteen seconds by 1932 (4:48.4). Female champions in those years swam the distance in 6:02.2 and 5:28.5. The women beat Johnny in 1956, Buster in 1964, and have now (1984) reached 4:07.10, half a minute quicker than Crabbe.

Baseball, by comparison, pits batter against pitcher and neither against a constant clock. If everyone improves as the general stature of athletes rises, then why do we note any trends at all in baseball records? Why do the best old-timers stand out above their modern counterparts? Why don’t hitting and pitching continue to balance?

The disappearance of .400 hitting becomes even more puzzling when we recognize that

average

batting has remained relatively stable since the beginning of modern baseball in 1876. The chart on the next page displays the history of mean batting averages since 1876. (I only include men with an average of at least two at-bats per game since I wish to gauge trends of regular players. Nineteenth-century figures [National League only] include 80 to 100 players for most years [a low of 54 to a high of 147]. The American League began in 1901 and raised the average to 175 players or so during the long reign of two eight-team leagues, and to above 300 for more recent divisional play.) Note the constancy of mean values: the average ballplayer hit about .260 in the 1870s, and he hits about .260 today. Moreover, this stability has been actively promoted by judicious modifications in rules whenever hitting or pitching threatened to gain the upper hand and provoke a runaway trend of batting averages either up or down. Consider all the major fluctuations:

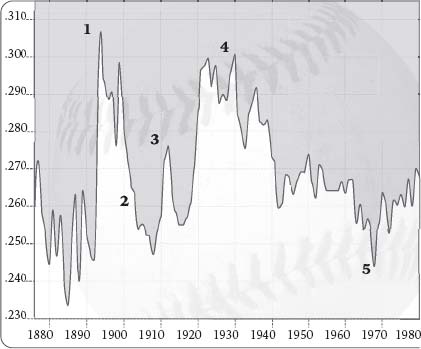

Averages rose after the pitching mound was moved back (1); declined after adoption of the foul-strike rule (2); rose again after the invention of the cork-center ball (3) and during the “lively ball” era (4). The dip in the 1960s (5) was “corrected” in 1969 by lowering the pitching mound and decreasing the strike zone.

After beginning around .260, averages began to drift downward, reaching the .240s during the late 1880s and early 1890s. Then, during the 1893 season, the pitching mound was moved back to its current sixty feet six inches from home plate (it had begun at forty-five feet, with pitchers delivering the ball underhand, and had moved steadily back during baseball’s early days). The mean soared to its all-time high of .307 in 1894 and remained high (too high, by my argument) until 1901, when adoption of the foul-strike rule promoted a rapid downturn. (Previously, foul balls hadn’t influenced the count.) But averages went down too far during the 1900s until the introduction of the cork-center ball sent them abruptly up in 1911. Pitchers accommodated, and within two years, averages returned to their .260 level—until Babe Ruth wreaked personal havoc on the game by belting 29 homers in 1919 (more than entire teams had hit many times before). Threatened by the Black Sox scandal, and buoyed by the Babe’s performance (and the public’s obvious delight in his free-swinging style), the moguls introduced—whether by conscious collusion or simple acquiescence we do not know—the greatest of all changes in 1920. Scrappy one-run, savvy-baserunning, pitcher’s baseball fell from fashion; big offense and swinging for the fences was in. Averages rose abruptly, and this time they stayed high for a full twenty years, even breaking .300 for the second (and only other) time in 1930. Then in the early 1940s, after war had siphoned off the best players, averages declined again to their traditional .260 level.

The causes behind

this twenty-year excursion have provoked one of the greatest unresolved debates in baseball history. Conventional wisdom attributes these rises to the introduction of a “lively ball.” But Bill James, in his masterly

Historical Baseball Abstract

, argues that no major fiddling with baseballs can be proved in 1920. He attributes the rise to coordinated changes in rules (and pervasive alteration of attitudes) that imposed multiple and simultaneous impediments upon pitching, upsetting the traditional balance for a full twenty years. Trick pitches—the spitball, shine ball, and emery ball—were all banned. More important, umpires now supplied shiny new balls any time the slightest scruff or spot appeared. Previously, soft, scratched, and darkened balls remained in play as long as possible (fans were even expected to throw back “souvenir” fouls). The replacement of discolored and scratched with shiny and new, according to James, would be just as effective for improving hitting as any mythical lively ball. In any case averages returned to the .260s by the 1940s and remained quite stable until their marked decline in the mid-1960s. When Carl Yastrzemski won the American League batting title with a paltry .301 in 1968, the time for redress had come again. The moguls lowered the mound, restricted the strike zone, and averages promptly rose again—right back to their time-honored.260 level, where they have remained ever since.

This exegetical detail shows how baseball has been maintained, carefully and consistently, in unchanging balance since its inception. Is it not, then, all the more puzzling that downward trends in best performances go hand in hand with constancy of average achievement? Why, to choose the premier example, has .400 hitting disappeared, and what does this erasure teach us about the nature of trends and the differences between past and present?

We can now finally explicate the myth of ancient heroes—or, rather, we can understand its partial truth. Consider the two ingredients of our puzzle and paradox: (1) admitting the profound and general improvement of athletes (as measured in clock sports with absolute standards), star baseball players of the past probably didn’t match today’s leaders (or, at least, weren’t notably better); (2) nonetheless, top baseball performances have declined while averages are actively maintained at a fairly constant level. In short, the old-timers did soar farther above their contemporaries, but must have been worse (or at least no better) than modern leaders. The .400 hitters of old were relatively better, but absolutely worse (or equal).

How can we get a numerical handle on this trend? I’ve argued several times in various articles that students of biological evolution (I am one) approach the world with a vision different from time-honored Western perspectives. Our general culture still remains bound to its Platonic heritage of pigeonholes and essences. We divide the world into a set of definite “things” and view variation and subtle shadings as nuisances that block the distinctness of real entities. At best, variation becomes a device for calculating an average value seen as a proper estimate of the true thing itself. But variation

is

the irreducible reality; nature provides nothing else. Averages are often meaningless (mean height of a family with parents and young children). There is no quintessential human being—only black folks, white folks, skinny people, little people, Manute Bol, and Eddie Gaedel. Copious and continuous variation is us.

But enough general pontification. The necessary item for this study is practical, not ideological. The tools for resolving the paradox of ancient heroes lie in the direct study of variation, not in exclusive attention to stellar achievements. We’ve failed to grasp this simple solution because we don’t view variation as a reality itself, and therefore don’t usually study it directly.