Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville (7 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy in Mudville Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

O

n October 6, 2001, for the first time in nearly a month of tragedy, the

New York Post

ran a headline on a different and happy subject. This screamer, despite its telegraphic mode and our preoccupation with other matters, conveyed a clear message in its numerical minimalism (to honor maximal achievement). The headline simply stated: “72.” Barry Bonds had fractured Mark McGwire’s “unbeatable” record for home runs in a single season, set at 70 just three years ago. (Two games later, he added another and finished the season with 73.) We are not callous. The thousands dead on September 11 shall remain in our lacerated hearts so long as we live. We now honor them by moving on in full memory, for “there is,” the Preacher tells us (Ecclesiastes 3:4), “a time to weep, and a time to laugh.”

First published as “A Happy Mystery to Ponder: Why So Many Homers?” in the

Wall Street Journal,

October 10, 2001.

As we cherish a happy note in the diapason of our emotional lives, we also wonder why this good news must dismember a comforting plateau of relative stability. Ruth’s 60 and Maris’s 61 set enduring standards, each lasting more than thirty years. We expected the same extended glory for McGwire’s 70, now fallen before we could even explore the appearance and meaning of this new Everest.

San Francisco Giant Barry Bonds hugs his son Nikolai after hitting his 70th home run against the Houston Astros on October 4, 2001. The next day, against the Los Angeles Dodgers, Bonds would hit his 71st and 72nd home runs to break Mark McGwire’s three-year-old record.

Credit: AP/Wide World Photos

We may, I think, best grasp Bonds’s achievement by struggling to understand two numerical aspects of his remarkable deed—one conventional among sporting records, the other surprising. First, Bonds’s 73 dingers follow the usual pattern of incremental improvement, rather than shattering breakthrough. When Ruth hit 60 in 1927, he broke his own record of 59 from 1921. Maris’s 61 in 1961 also added a minimal increment. These heights, then, slide evenly down to Greenberg and Foxx at 58, Wilson at 56, Mantle at 54, etc. McGwire’s 70 seemed to fracture the scale, but the disturbing gap quickly filled, restoring a comforting incrementalism with McGwire at 70, Sosa at 66 in the same 1998 season, McGwire at 65 in 1999, Sosa with 64 this year, and Sosa again with 63 in 1999.

But in a second and disconcerting feature, this Giant has broken all decorum by so accelerating the pace of fracture that we can hardly stabilize our admiration before transcendence forces a reorientation. Sure, “records are made to be broken,” as the cliché proclaims. But truly great records should endure for a

little

while, at least long enough to potentiate the stuff of legend across a single generation: “Son, I remember when…Oh yeah, Dad, you were there? Really, honest!”

Our discombobulated lives need to sink some anchors in numerical stability. (I still have not recovered from the rise of a pound of hamburger at the supermarket to more than a buck.) Ripken waited a long time to break Gehrig’s feat of endurance. DiMaggio’s fifty-six-game hitting streak remains unchallenged (with a distant forty-four for second place), but may one day fall. Cy Young’s 511 career victories will never be exceeded unless surgeons invent an iron arm, or pitchers return to the old practice of working every fourth day and finishing what they start.

This acceleration therefore raises a question that I, as a statistician of the game, generally regard as inappropriate. Broken records usually demand no special explanation, despite our inclination to view any increment as a uniquely heroic feat accomplished for a particular reason of valor. In this case, however, we do need to understand our current epidemic of homers, permitting three great players to exceed, and several others to challenge, all within the past four seasons, a plateau of 60 reached only twice before in 120 years of major league baseball. No random “blip” can encompass so much done so quickly by so many.

I tend to dismiss the three most common conjectures, but wish to defend a fourth notion rarely aired in this growing debate. First, we cannot ascribe this outburst to the sociology of changing fan preferences for displays of raw power. The great sluggers of the past—from the versatile Ruths to the single-minded Kiners or Killebrews—played “long ball” just as assiduously, and the domination of hitting over pitching peaked during the 1920s and 1930s, not in modern baseball.

Second, despite all conspiratorial suspicions and reasoned arguments, numerous tests of old vs. new balls find no “juicing up” of the projectile, either consciously ordered or accidentally achieved. Third, and finally, knee-jerk arguments about the general decline of pitching won’t wash. I suspect that Ruth enjoyed better prospects in his time, before the “invention” of relief pitching in several varieties of subspecialization. (At the very least, he never had to hit against himself, for Ruth was also baseball’s best left-handed pitcher.) I wonder how many dingers the Babe hit off tired starters in the late innings?

Only one explanation makes any sense to me as an innovation that might sufficiently boost the output of the best sluggers. Several years ago,

American Heritage

asked me to write an article on the greatest athlete of the twentieth century. I considered the inestimable Jordan and Ali, but finally decided upon the consensus favored at midcentury (when, as a sports-addicted kid, I read everything on this subject): Jim Thorpe, who put miles of space between himself and the clumped second-to fifth-place finishers in both the pentathlon and decathlon of the 1912 Olympics, who reigned as the best player in American football, and who also performed adequately in major league baseball (whereas Jordan really couldn’t hit a curve and barely broke .200 in a full minor league season). Contemporaries invariably described Thorpe as an Adonis, whose gorgeous body bristled with strength and muscles. But if you judge a photo of Thorpe by contemporary standards of bodily perfection, you will probably recall the ninety-eight-pound weakling of those old Charles Atlas ads. Thorpe now looks scrawny and ill-developed, no match for half the guys at the local gym.

I therefore suspect that one consistent and important thing separates then from now: scientific weight training for highly specific changes in particular muscles and groups—a regimen now rigidly followed by all serious athletes, yet completely unknown in Ruth’s time. Scientific training, by itself, does nothing, and cannot convert even a very good hitter into a home run champion. But such assiduous, specialized work, rigorously followed by those few surpassingly gifted athletes who combine the three essential attributes of bodily prowess, personal dedication, and high intelligence, can probably raise Greenberg’s 58 to McGwire’s 70.

To Mark McGwire, a truly splendid man who deserved to savor a longer reign, we can only say that “there is…a time to get, and a time to lose: a time to keep, and a time to cast away.” You were the firstest with the mostest. We will always love you, and revere your amazing grace in that wonderful season. You and Sammy (and the ghosts of Roger and Mickey) will always be the boys of our most exquisite summers. And to Barry Bonds, who by quirks of temperament has never matched McGwire in public appeal, but who did his deed with honor, consistency, and fortitude at the most tragic of all times, may you enjoy every moment as you remember another verse in the third chapter of Ecclesiastes: “There is nothing better than that a man should rejoice in his own works; for this is his portion.” Barry, that was one helluva portion! God bless you, and God bless us every one. You gave us some lightness of being to face an unbearable time.

I

was nine years old when the Yanks brought up Mickey Mantle in 1951. I hated him. DiMaggio was my hero, but even I could tell his skills were eroding. I longed for that centerfield job, and I knew that it would be mine if only DiMag could hang in there long enough for me to finish high school. But now, at the brink of realizing this beautiful fantasy, I faced a usurper from Commerce, Oklahoma.

In 1952 I began to change my mind, for even a child can empathize with the victims of cruel treatment and ill fortune. One day, as the senseless booing continued to envelop Mantle (he hit .311 with twenty-three homers in his sophomore year), Yankee emcee Mel Allen broke the cardinal rule of dramatic performance by forsaking his appointed role and conversing directly with his audience. As I listened on the radio, Allen leaned out of his press box and accosted a fan in the midst of a raucous Bronx cheer: “Why are you booing him?” The fan replied, “Because he ain’t as good as DiMaggio”—and Allen, rendered momentarily speechless (for once) by simple fury, busted a gut.

“Mickey Mantle” first appeared in

Sport

magazine, December 1986.

Suddenly I realized something in a cold sweat. Mickey was actually closer to me in age (ten years older) than he was to DiMaggio (nearly seventeen years younger). Before then I had simply lumped all full-sized people into the single, undifferentiated category “adult.” But Mickey was more like me, and I would have been scared shitless out there in center field. My heart went out to him—as it had, for the first time, when he caught his spikes on a drainage spout during the 1951 World Series and almost ended his career with the first and most serious of many leg injuries.

In 1956, his magical year of the triple crown, I came to love Mickey Mantle. I suspect you had to be a kid growing up on the streets of New York to appreciate the context in all its glory. The fifties—before the great betrayal and flight to California by Stoneham and O’Malley—were the greatest baseball years that any single city ever experienced. I was lucky to be the right age in the right place. We had three great teams (and seven subway World Series in the ten years between 1947 and 1956). All Yankee fans hated either the Giants or Dodgers with blazing passion (we loved individual players, but the corporate entity was Satan incarnate). Affiliation was no laughing matter or passing fancy. I received my worst street beating—and deserved it—when I had the temerity to admit, while playing with a cousin and his friends in Brooklyn, that I was a Yankee fan.

Success had smiled on my side. The Yanks had beaten the Dodgers in all five of their subway series between 1941 and 1953. But then, in 1955, it happened—the impossible, the soul searching, the unimaginably painful, the always feared but never really anticipated. The Dodgers won in seven and the

Brooklyn Eagle

featured on its front (not its sports) page a smiling derelict under a banner headline “Who’s a Bum?”

We waited all year for revenge, through a winter of discontent and into a summer of Mantle’s blooming greatness. We recovered our pride in 1956 (the last subway series), a victory sweetened to true perfection by Don Larsen’s twenty-seven bums up and twenty-seven bums down. Mantle both won and saved that game for Larsen, first with a home run off Sal Maglie, and then with a dandy catch on Hodges’s 430-foot drive to left-center.

His next year,

1957, was even better, probably the greatest single season by any player in baseball’s modern era. Mantle’s achievements in 1957 have been masked by a conspiracy of circumstances, including comparison with his showier stats of the year before and the fact that his career-best batting average of .365 came in second to Ted Williams’s .388. In 1957 Mantle had a career high of 146 walks, with only 75 strikeouts. (In no other year did he come even close to this nearly two-to-one ratio of walks to strikeouts; in ten of eighteen seasons with the Yanks, he struck out more often than he walked.) This cornucopia of walks limited his official at-bats to 474 and didn’t provide enough opportunity for accumulating those (largely misleading) stats that count absolute numbers rather than percentages—RBIs and home runs for example. Superficial glances have led to an undervaluing of Mantle’s greatest season.

Sabermetrics (or baseball number crunching) has its limits and cannot substitute for the day-to-day knowledge of professionals who shared the playing field with Mantle, yet numerical arguments command our respect when so many different methods lead to the same conclusion. As Bill James points out in his

Historical Baseball Abstract

, all proposed measures of offensive performance—from his own runs created for outs consumed, to Thomas Boswell’s total average, Barry Codell’s base-out percentage, Thomas Cover’s offensive earned run average, and Pete Palmer’s overall rating in

The Hidden Game

—judge Mantle’s 1957 season as unsurpassed during the modern era. Consider just one daunting statistic, Mantle’s on-base percentage of .512. Imagine getting on base more often than making an out—especially given the old saw that, in baseball, even the greatest fail about twice as often as they succeed. No player since Mantle in 1957 has come close to an on-base percentage of .500. Willie Mays reached .425 in his best year.

In 1958 the Yankees’ general manager, George Weiss, a tough old bastard, had the audacity to offer Mantle a contract with a $5,000 pay cut, reasoning that 1957 had not matched his triple crown performance of the year before!

In a nation

too young to generate truly mythical figures, Americans have been forced to press actual, rounded people into service, and to grant these special folks a dual status as human and legend. When, as with Mickey Mantle, sports heroes exemplify the cardinal myths of our culture, their conversion to parable and folklore is all the more rapid and intense.

Mantle’s legend is the most powerful and enduring since Babe Ruth’s because he mixed into the circumstances of life and career three of the most potent folk images of American mythology. First, Mantle was young, handsome, and bristling with talent. His skills satisfied both sides of the great nature-nurture debate, for he combined the struggle of Horatio Alger with the muscles of John Henry. He was big and strong and could hit a ball 565 feet. His father, an impoverished miner, lived and breathed for baseball. He named his son after his favorite catcher, Mickey Cochrane, and made a playing area (usually against a barn) wherever they lived. Mutt Mantle converted his son, a natural righty, into a switch-hitter by delaying dinner each night until Mickey had taken enough successful swings from the left side.

Second, Mantle was the gullible and naive farmboy who prevailed by good will and bodily strength in a tough world. Commerce, Oklahoma, as Mantle describes it, is a movie theater, a cafe, four churches, a motel, and a lot of grassroots (or rather slag heaps, in this bleak mining region) baseball. Mantle’s father labored in the mines all his brief life, except for a failed stint at farming. Mantle grew up as an Okie in the depths of the Depression—a family that stayed while Tom Joad and his compatriots moved westward.

Third, his country innocence met the Big Apple. Mickey hit New York, symbol of immensity, rapacity, and sophistication, at age nineteen. He was soon bilked by a sleazy agent and victimized in a phony insurance scheme. His dad was so awed and disoriented on his first visit to Manhattan that he mistook the monument of Atlas at Rockefeller Center for the Statue of Liberty.

Yet even this conjunction of unparalleled talent and naivete alone in the big city cannot in itself set an enduring legend. Mythological heroes need flaws and tragedies, the Achilles’ heel that defines an accessible humanity. Mantle’s innocence was tainted by tragedy and dogged by disappointment. He did it all for (and because of) his father, but Mutt Mantle lived to see only the dicey beginnings of Mickey’s then uncertain career. After Mickey’s injury in the 1951 World Series, Mutt took his son to Lenox Hill Hospital. As they got out of the cab, a hobbled Mickey put his weight against his father, and Mutt collapsed on the sidewalk. They ended up together in a double room—Mickey to recover from torn ligaments, his father to begin the slow process of dying from Hodgkin’s Disease, a form of cancer now usually curable.

Serious injuries continued to plague Mantle. He never could put together a long string of healthy seasons, and he often played in pain, wrapped in more bandages than Boris Karloff as Im-Ho-Tep the Mummy. He had four glorious seasons (1956–1957 and 1961–1962) but also several distinctly subpar years. Playing hurt in his last season (1968), his skills prematurely eroded, Mantle batted .237 and watched in frustration as his lifetime batting average slipped below the magic line to .298.

Moreover, Mantle put his heart and life into baseball before the era of great material reward. His top salary never reached even half of what any utility infielder might command today. Year after year he was forced into humiliating negotiation with Weiss, the archetypal skinflint and belittler of men. He worried continually about finances, and diverted much energy to schemes that no one in his position would dream of needing today. He moved from Oklahoma to Dallas in order to run a bowling alley that he hoped would secure his financial future (though it eventually failed). He established a chain of country-cooking outlets, also unsuccessful in the long run. The sport that had been his lifelong obsession did not repay his investment, and he joined Willie Mays in heartless and senseless exile after commissioner Bowie Kuhn ruled that no employee of an Atlantic City casino could also represent major league baseball (a galling judgment since widely revoked by Peter Ueberroth).

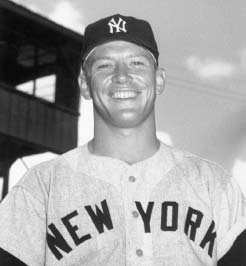

Mickey Mantle in 1955. Mantle died on August 13, 1995.

Credit: Bettmann/Corbis

I do not

wish to debunk this legend. It contains enough truth to pass muster, and, as argued above, Mickey the myth has a different (and legitimate) status from Mickey the man. Still, the rounded man is so much more interesting than the cardboard legend. The myth really fails only in one crucial way. Achilles’ heels are blemishes beyond the control of heroes. It was not Achilles’ fault that his mother had to grasp some part of his anatomy when dunking him in the river Styx. But Mantle’s disappointments were not, as the legend holds, solely the result of congenitally weak legs and an unlucky series of freak accidents.

Though no one ever matched Mantle’s fierce commitment and competitive desire, he did not train properly and actively disregarded almost all medical advice for rehabilitation from his injuries. As for the injuries themselves, several were just bad luck, but others (covered up at the time) were the consequences of foolishness and excessive drinking. Mantle teetered for years on the edge of a serious problem with alcohol, and his legendary late nights cannot be called a mere innocent exuberance of youth, but a pattern that hurt and haunted his career.

Mantle’s autobiography,

The Mick

, presents an honest account of this tension between high jinks and harm. Mantle told me that, if his book contains any lesson, he hopes that kids with great talent will understand why they must take better care of their bodies. As we sat in the press box three hours before a night game with Baltimore, Mantle looked down on the field and said to me witsfully, “Look, there’s Mattingly, my favorite player. I love the man. He’s out there for extra batting practice with the rookies. He doesn’t need to be there; I never was.”

Mantle’s failure to sustain his full potential is all the more poignant because he harbors deep regret, and for reasons that transcend mere ambition and desire for personal fame. He writes in his autobiography: “When somebody once asked me what I’d want written on my gravestone, I answered, ‘He was a great team player.’”

Now I’m not from Commerce, Oklahoma. I’m a prototypical cynical, streetwise, New York kid. When I read such statements, upholding values we all mouth but seldom follow, I get suspicious and assume a bit of dissembling. But I accept Mantle’s judgment absolutely. Everything fits too well. Mantle struggling for his team and not for personal stats is the man himself, not the myth.

I remember so clearly, because I watched the scene often, how Mantle would circle the bases after a home run—head down and as fast as he could, as if to shut out the personal adulation and limit its duration.

I asked him about his proudest achievements and deeper disappointments. He takes greatest pride, he said, not in his triple crown or his home runs, but in playing more games as a Yankee (2,401) than any other man. As his worst moments he cited his return to the minors during his first season in 1951 (not sufficient help to the team) and Bill Mazeroski’s home run that won the 1960 World Series for the weaker Pittsburgh club (“I cried all the way home in the plane after that”)—though Mantle had played his heart out and harbored no feelings of personal failure. Above all, he told me, he regretted his “stupidity” (his own word, and the only one uttered with real vehemence during our interview) in allowing his prodigious skills to erode more quickly than nature required, forcing his retirement just before his thirty-seventh birthday, while those who share Mantle’s fire for the game but take better care of themselves, the Yazes and the Roses, play with grace well into their forties.