Truman (99 page)

Authors: David McCullough

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Political, #Historical

Asked once by reporters for his view of her appearance, Truman said he thought she looked exactly as a woman her age ought to look.

Many people, meeting Bess Truman for the first time, were surprised by how much younger and more attractive she appeared than in photographs, where her expression was often somber, even disapproving. Something seemed to come over her in public, and particularly when photographers pressed in on her. In receiving lines she often looked bored, even pained, as if her feet hurt—a very different person from the one her friends knew. A Louisiana congressman’s wife, Lindy Boggs, would remember how vivacious the First Lady could be while arranging things for a reception, what delightful company she was behind the scenes. “And then…the minute the doors would open and all those people would begin to come in, she would

freeze,

and she looked like old stone face. Instead of being the outgoing, warm and lovely woman that she had been previously, the huge crowds simply made her sort of pull up into herself.”

Where Eleanor Roosevelt had seen her role as public and complementary to that of her husband, Bess insisted on remaining in the background. “Propriety was a much stronger influence in her life than in Mrs. Roosevelt’s,” remembered Alice Acheson, the wife of Dean Acheson. It was widely known that Bess played cards—her bridge club from Independence had made a trip to Washington in the spring of 1946, stayed several days at the White House, and was the subject of much attention in the papers—and that she and Margaret, unlike the President, were movie fans. Bess also loved reading mysteries and was “wild” about baseball, going to every Senators game she could fit into her schedule. But she had no interesting hobbies for reporters to write about, no winsome pets, no social causes to champion or opinions on issues she wished to voice publicly. Her distaste for publicity was plain and to many, endearing. She refused repeatedly to make speeches or give private interviews or to hold a press conference, no matter how often reporters protested. “Just keep on smiling and tell ‘them’ nothing,” she advised Reathel Odum. “She didn’t want to discuss her life,” Margaret remembered.

Two early public appearances had turned into embarrassments. She had been asked to christen an Army plane, but no one had bothered to score the champagne bottle in advance, so it would break easily. She swung it against the plane with no result, then kept trying again and again, her face a study in crimson determination. The crowd roared with laughter, until finally a mechanic stepped in and broke the bottle for her. Truman, too, had been amused, as was the country when the newsreel played in the movie theaters, but not Bess, who reportedly told him later she was sorry she hadn’t swung that bottle at him.

The other episode concerned her acceptance, in the fall of 1945, of an invitation to tea from the Daughters of the American Revolution at Constitution Hall, a decision protested vehemently by Adam Clayton Powell, the flamboyant black congressman and minister of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, whose wife, the pianist Hazel Scott, had been denied permission to perform at Constitution Hall because of her race. Bess, however, refused to change her mind. The invitation, as she wrote to Powell, had come before “the unfortunate controversy,” and her acceptance of such hospitality was “not related to the merits of the issue.” She deplored, she said, any action that denied artistic opportunity because of race prejudice. She was not a segregationist, but she was not a crusader either. Powell responded by referring to her publicly as “The Last Lady of the Land,” which caused Truman to explode over “that damn nigger preacher” at a staff meeting, and like Clare Boothe Luce, Powell would never be invited to the White House.

When at last in the fall of 1947 Bess agreed to respond to a questionnaire from reporters, her answers were characteristically definite and memorable:

What qualities did she think would be the greatest asset to the wife of a President?

Good health and a well-developed sense of humor.

Truman, President in his own right, and Vice President Alben Barkley on the reviewing stand, Inauguration Day, January 20, 1949.

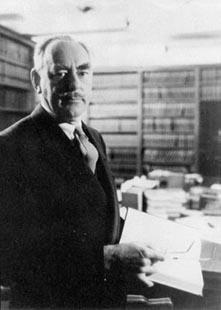

Secretary of State Dean Acheson, by far the strongest, most brilliant, and most controversial member of Truman’s Cabinet through all of the second term. “Do you suppose any President ever had two such men with him as you and the General [Marshall]?” Truman would later write to Acheson.

Truman’s World War I pal and presidential military aide, General Harry Vaughan, who was seen as the ultimate White House “crony.”

Alger Hiss, symbol of Republican charges that the administration was “soft on communism.”

Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy, whom Truman loathed and mistakenly believed time and the truth would soon destroy.

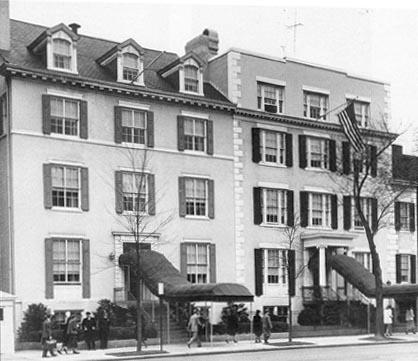

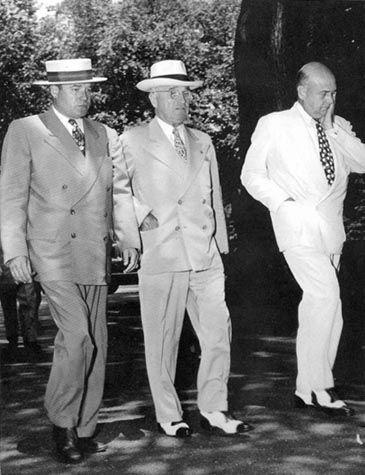

Opposite: At midday, June 27, 1950, having announced that Amercian forces would intervene in Korea, Truman, accompanied by Attorney General J. Howard McGrath (left) and Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson, heads from the White House to his temporary residence across Pennsylvania Avenue at Blair House (above). It was at Blair House, after meeting there with his advisers the two previous nights, that Truman reached his fateful decision on Korea—the most difficult and important decision of his presidency, he felt.

On October 15, 1950, a month after the stunning success of General Douglas MacArthur’s surprise assault at Inchon (above), Truman and MacArthur met at Wake Island in the Pacific, driving off for a first private talk in a battered Chevrolet (below). By all signs the Korean War, Truman’s “police action,” was nearly over.