Trusting Calvin (20 page)

Authors: Sharon Peters

The dog's bowels were no longer in his control, and when they loosed onto the floor Max cleaned him up gently and moved close again to hold him.

“It doesn't matter, Boychickânot at all. Don't worry,” Max said. He wanted his dog to go gently, without worry or concern, knowing his partner would take care of everything, just as each of them had always done for the other.

On that same date five years earlier, Max realized, he had been similarly offering what little comfort he could, anguishing over the loss he knew would soon come . . . at the bedside of his wife in the hours before she died.

Boychick would sleep for a few minutes, and then awaken and wriggle closer, Max feeling him looking up at him, as if to imprint every inch of this man on his brain before he had to leave. Max did the same, in his way, slowly running his hand along the big, proud muzzle, the rounded curve of his head, the velvet ears.

Soon after the sun rose the next day, Helen arrived to drive Boychick and Max, exhausted, forlorn, to the veterinarian's office.

At 8:15, Boychick took his last breath, Max nearby.

A few weeks later, a trainer arrived with another dog, a yellow Lab called Derrickâa dumb name, Max announced, and promptly changed it to Duke. The two meshed well together, and Max was as pleased as the trainer with how quickly they understood each other. But at the end of the third day Duke was limping badly.

Max's vet examined the dog. Probably just a muscle sprain, he said, prescribing pills and a recommendation to discontinue training for a couple of days. The limp worsened, though, and on the second visit the vet did X-rays, discovering a congenital problem with Duke's shoulder joint. He wouldn't be a guide dog for Max, or anyone else.

Another dog hadn't worked out.

In July, seven months after Boychick died, after too many days of too-limited activities, Max traveled back to the school for another abbreviated class. There he was matched with a rangy black Lab with toffee-colored eyes named Tobin, plucked from a litter of eleven puppies born at the school's breeding facility, and raised by a Virginia Beach family. He was the only one of his littermates ultimately deemed ideal for guide work, and it was as if he had snatched a tiny particle from each of his siblings' impressive traits to bolster his own. Tobin demonstrated every quality the trainers wanted to see in a potential guide dog, but a fraction more of each across the board. Focused beyond imagination. Adaptable to the highest order. So eager when the harness came out, it was easy to think he probably thought about working while he slept.

He had the self-confidence of Calvin and Boychick, laced with a large measure of extroversion, a quality that in earlier years wouldn't have been suitable for Max, but now was fine. Tobin also had a moderate walking pace, not too fast and not too slow, like Max, and what is called a “medium” pullâMax's preferenceâmeaning the dog neither hauls his handler forward nor keeps so tightly locked with the person's pace that almost no pressure from the animal is detectable.

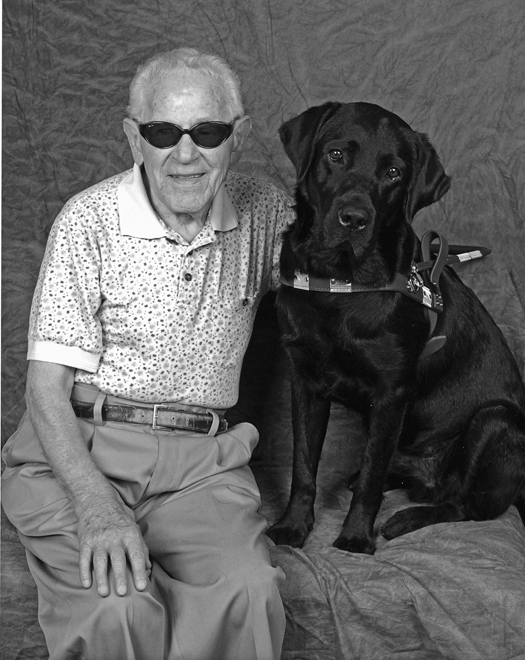

Max and Tobi

COURTESY OF GUIDING EYES FOR THE BLIND

Again, Max had to contend with what he called the “not-quite-Âperfect glove fit” period, during which he was not as comfortable with Tobin as he had eventually become with Calvin and Boychick. He very much liked this dog, though. He liked his demeanor and his focus. He liked the way he moved and the way he listened. He liked his steady unflappability no matter what, even in the early days when a dog has many new things to process and accommodate.

He did not, however, like the name.

Tobin became the sportier, softer-sounding Tobi.

Back at home, the dog and the man bonded instantly and deeply. There were tiny adjustments, as always, as each went through the process of becoming fully comfortable and completely in tune with each other, but it happened with stunning speed. The dog made it clear in every way he could that he was intensely devoted to the man, that he was happyâthrilled, in factâto do whatever Max might ask of him.

Max thought back to the difficult early days with Calvin, recalled thinking at the time that he simply wasn't the kind of man a dog could bond with. He hadn't been. And now this, a relationship forged, fast and intense.

Max taught Tobi the neighborhood, the locations of the mailbox and other regular stops, and in short order the dog was adeptly maneuvering Max around construction cones and puddles with confidence and ease. Tuesdays at the library continued with Tobi, as did regular appearances to speak about the Holocaust, Tobi half-dozing sometimes but always ready, at the most subtle signal, to pop to his feet and do Max's bidding.

“Come on, buddy boy,” Max would say quietly, and Tobi would tremble with excitement, certain that once again this man had something great up his sleeve.

Tobi quickly decided Max's friends and family members were utterly enchanting, and he developed personalized greetings for most of them, always demonstrating his great delight at the company, sometimes wearing an expression of happy surprise, sometimes joy, sometimes something that looked very much like amusement, depending on the person and the circumstance.

Tobi, Max fully accepted, was not Calvin, the goof with the great sense of humor and the instant capacity to alter his notion of what his task was in times of varying needs, including, in the early days, how to build a relationship of trust with a man unable to contribute much at first. He was not Boychick, the exceedingly gentle soul with unmatched insight into human emotions and the ability to draw them into sharing the place of warmth and love he offered.

He was, simply and wonderfully, Tobi: an always-ready, ever-vigilant dog with a winning attitude and a laser focus on his man.

Soon after the shiny black dog entered his life, Max began signing his e-mails “From Max. And Tobi.”

Nine

That Calvin, Boychick, and Tobi dependably maneuvered Max around the obstacles and dangers of life surprises no one. It's what they were trained to do. But guide dogs also provide and generate many benefits that are not strictly part of the job of getting a person from one place to another.

Sooner or later, most guide dogsâand their exactingly trained brethren, classified as “service” or “assistance” dogs (including mobility dogs, hearing-assistance dogs, and psychological-assistance dogs)âwill take an action or impact their handlers in ways so far beyond what their trainers or the science can fully explain, it almost seems magical. That sort of thing occurs so regularly, in fact, that many experts and handlers now regard the bonus gifts these animals confer as part the package.

“There's training, and there's also what the dogs do that no one can really explain,” says Karen Shirk, whose 4 Paws for Ability in Xenia, Ohio, has placed hundreds of service dogs to help children with a range of disabilities, from seizures to mobility issues. “You can't predict exactly how this thing, whatever the thing winds up being, will unfold, exactly what form it will take. It's very individual and situational. You can only know that the dog will zero in on a need and something will happen.”

Karen herself had such an experience with her own service dog, a coal-colored German shepherd named Ben. Karen suffers from myasthenia gravis, a neuromuscular disorder that weakens muscles, including, in her case, those required for breathing. One evening she lapsed into unconsciousness at home when, upon doctor's advice, a visiting nurse had increased her medications. Ben must have concluded from her shallow, ragged breathing that she wasn't merely napping. When the phone rang, Ben knocked it off the cradle and barked incessantly until the caller realized there was a problem and sent someone.

“Ben wasn't trained to do this,” Karen says, “but somehow he knew it would bring help.”

Jan Abbott, who worked with Calvin and Boychick and is now an instructor at The Seeing Eye, often speaks of a German shepherd who made a different kind of on-the-spot decision. Guide dogs are trained never to jump on people, and such a dog would never jump on her own handler. But one morning when a truck hurtled onto the sidewalk and roared toward them, the dog leapt atop her woman, knocking her out of the vehicle's path. The dog didn't survive. Her handler did.

Some of the unexpected bonuses service dogs deliver are direct, life-saving interventions, but most are of a different sort, changing their handlers' lives not only through their assistive skills, but also by providing such a high level of unerring emotional abutment that they alter how the handlers regard the world, live their lives, and engage in relationships.

That this is the case is not exactly a far-fetched notion born of sterile soil. People have long recognized the life-altering effects of animals. Besotted owners of household petsâthose of all species and with no special assistive trainingâhave for centuries boasted of the healing properties or miracles their companions have wrought, rescuing them from fires or mountain lions or swollen rivers, saving them sometimes from the depths of despair, willing them back to health when medics and medicines had accomplished little.

Experts finally started to take note and seek understanding in the final decades of the twentieth century. The investigations began, and the discoveries rolled out.

Animals of all kindsâcats, goats, even fishâfoster emotional and cognitive growth in children, they found.

They can serve as important balms to people in transition, such as those dealing with divorce or the death of a spouse.

Some people may find bonding with pets easier than with humans because animals are largely indifferent to their owners' material possessions, social status, well-being, and interpersonal skills.

Elderly women living alone are less lonely, less agitated, and more likely to be optimistic and engaged with future planning if they have a pet.

And dogs seem to provide benefits even beyond those that come from animals in general. Researchers have documented in recent years many physiological and psychological benefits of having a dog, including: petting a dog decreases blood pressure and anxiety; having a close relationship with a dog appears to be a buffer against stress; and dog owners have greater self-esteem, a stronger sense of security, and are often perceived to be happier and healthier.

People with service dogs accrue those benefits, of course, but possibly in ways and measures much larger. Researchers have only recently begun to explore the intricacies of the humanâservice dog relationship, but the findings are compelling.

Just six months after being partnered, handlers of service dogs have reported improvements in self-esteem, the ability to influence their own destiny, and in psychological well-being, as well as social integration. In another study, people with assistance dogs perceived themselves as being healthier than people without them. Hearing-impaired people rated themselves less lonely after receiving a hearing-assistance dog; seizure-prone individuals paired up with seizure-detection dogs reported a reduction in anxiety about their seizures and, over time, a 50 percent reduction in actual seizures; and parents of children with autism reported that having a service dog not only provided additional safety for the child, as intended, but the children also became calmer, and family dynamics improved.

A significant measure of these extra things that service dogs bestow may be attributable to the fact that “as dogs, in general, have evolved with us over the centuries, they've become very adept at picking up cues about our behaviors,” in ways “sometimes not obvious to us,” says Alan M. Beck, director of the Center for the Human-Animal Bond at Purdue University's School of Veterinary Medicine. And service dogs, in particular, probably “evolve into being better partners as the person and dog spend more time and experiment together.” This may explain, he supposes, why service dogs seem especially inclined to sense and react to specific needs, though researchers have not yet discovered the precise process by which this occurs, how often it occurs, or even exactly why or in how many ways their handlers react to their ministrations.

But if some of the side benefits of having a service dog have not yet been fully investigated and completely explained, they occur with such regularity that they're considered by many trainers and handlers absolute truths merely awaiting formal research verification and insight.

An almost universal outcome of having a service dog, for example, is the enhancement to “social identity,” as dogs draw their partners into richer, more engaged lives.

The “social lubricant” or icebreaker benefit of being out and about with a dogâany dog, in factâis one that, although not yet studied among disabled people, has been repeatedly noted in other populations. There's just something about a person holding the end of a leash that makes others more inclined to approach or speak or smile, researchers have found. And many disabled people report that the icebreaker impact of their service dogs is especially profound.

“I am much cuter when I have my dog, apparently,” offers attorney Natalie Wormeli of Davis, California, with a laugh. Diagnosed with multiple sclerosis when she was nine and significantly visually impaired by her teens, she received her first guide dog, Lance, a sensitive border collie, just before heading off to college.

“Lance became very popular, and by extension, so did I.”

With each passing year, MS stole more of her vision and most of the capabilities of her arms and legs until she was completely blind and in a wheelchair. After three decades and three more assistance dogsâBruno, a hulking hundred-pound yellow Labrador retriever; Nugget, a big Lab and golden retriever mix; and now Jeeves, a gentle golden retriever, all trained by Paws with a Cause in Wayland, Michigan, to be guide-dogs-cum-mobility dogsâshe has developed a belief built on the certainty that comes from hundreds of firsthand observations: People are less “put off or embarrassed or intimidated or whatever specific thing a particular person experiences” when the disabled person has a dog at his or her side.

Natalie and the people she encounters move from chatting about the service dog to chatting about their own dogs, to chatting about dogs in general, to gliding into normal social discourse of the sort that simply doesn't happen often or quickly with a disabled person sans dog, she says. It's an experience echoed by nearly every disabled person who invites an assistance dog into his or her life.

Kate Lawson of New York spent her first “fear-filled” year at Goucher College in 2008, “shy, unwilling to participate in class or go to unfamiliar places.” Severely visually impaired since birth, she felt “limited,” she says, “and because of that mind-set, I

was

limited.”

Kate applied for a dog from Guiding Eyes for the Blind, and during the summer after her freshman year was matched up with Bambi, an outgoing black Labrador retriever.

“When I returned for my sophomore year, I was shocked by the amount of attention Bambi and I received. I was used to being practically invisible, and now people were drawn to us like ants to a picnic basket. I met some of my closest friends because I was willing to be more open with others.”

Another widely recognized by-product of having a service dog is an increased capacity to build and follow through with goals and dreams, in large part because of the confidence disabled people seem to gain from having these animals in their lives.

Natalie Wormeli, the California attorney, learned from her trainers that “if you're anxious in a situation, you must at least fake being confident and relaxed, because you transmit whatever emotion you're feeling through the leash to the dog, and you don't want the dog to start feeling edgy.”

And so in every situation in which she might, as a blind woman in a wheelchair, have felt discomfort about a potentially negative reactionâjob interviews and social outings and the like âshe generated the strength necessary so as not to telegraph nervousness to her service dog.

“The discovery you make,” she says, “is that if you fake confidence long enough, you become confident.”

But it's more than just the boost that feigning confidence gives a person, Natalie says. There's a real, almost tangible shift in the attitude of a disabled person when she knows she is projecting an image of self-reliance and competency.

“It is quite a thing to go from being pushed in a wheelchair by someone to letting the dog help you get where you need to go in a wheelchair,” says Natalie. On job interviews after she passed the bar exam, that made all the difference. “You go from being totally passive, being pushed in a wheelchair, which was the case when I was between dogs, to, when I was part of a team with a dog, rolling in and doing my part. I didn't have to ask for someone to push elevator buttons to get to the office or to open the door once I got there. The dog did those things. My attitude was so much better, and so was their [potential employers'] receptiveness.”

She suspects that, without the dogs who have ushered her through what has become a successful career, she might have pulled back before she even started, pursued something else that required less people contact, less venturing out.

Even as her physical capabilities diminished steadily during the years, each dog, without fail, altered his ways of working with her and supporting her to meet her ever-changing physical and emotional needs. They didn't go back to school to learn new skills to help her. “They figured out how to adapt to me and for me.”

Disabled people tackling challenges on a much higher level than previously thought possible, as Natalie experienced, is, in fact, common among many who get service dogs.

Kate Lawson and Bambi navigated the subways and buses of Manhattan with such ease during college breaks that she decided to take a semester abroad to study psychology at the University of East Anglia in England, a prospect that before Bambi would have seemed impossible, and after Bambi was “exciting.”

Yes, Bambi did the job she was trained to do, but something happens to the heart and soul of a person who finds herself no longer alone in the near-dark. It's hard to put into words, Kate says, but the mere presence of this creature, always cheerful, always willing, takes a great deal of the psychological weight of the disability away.

Indeed, it's widely acknowledged that disabled people often experience a lightening of spirit when paired up with service dogs. Part of that, though not all, comes from being able to rely less on other people for the routine tasks of daily living.

“It's draining to have to ask for every little thing. It wears you out emotionally,” says Natalie Wormeli. “I have such limited ability in my hands now that I can do very little on my own. Of course I have to rely on others. But I can prioritize what I have to ask from them, and for all the rest, from opening doors to picking up things I drop, I can rely on Jeeves. It may sound small, but it's huge if you are living it.”

No less numerous are the examples of how service dogs have becalmed and softened disabled people, many of whom had erected seemingly rock-hard and impenetrable self-protective emotional barriers before their dogs arrived. Even Kate Lawson, an upbeat young woman, struggled with anger in high school. “I felt comfortable with my visual impairment, but people around me weren't, and that was a constant friction I felt.” The choler trickled away like a slow-moving brook after Bambi came into her life. “I live a much fuller life, much more immersed, in part because I let go of that earlier stuff.”

That service dogs squire in all of these additional benefits beyond their primary purpose has become fairly widely acknowledged in recent years, even in research circles, although “the mechanisms by which all of this transpires are unknown in many cases,” says UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine professor Lynette Hart, who has been studying the complex interplay of people and animals for many years. “Anyone who is somewhat socially isolated, who may have some medical problems, both of which can often be the case with disabled people, can feel profoundly alone. The ways in which service dogs reduce that can be quite similar and yet very specific to the individual, and that's an interesting phenomenon worthy of study.”