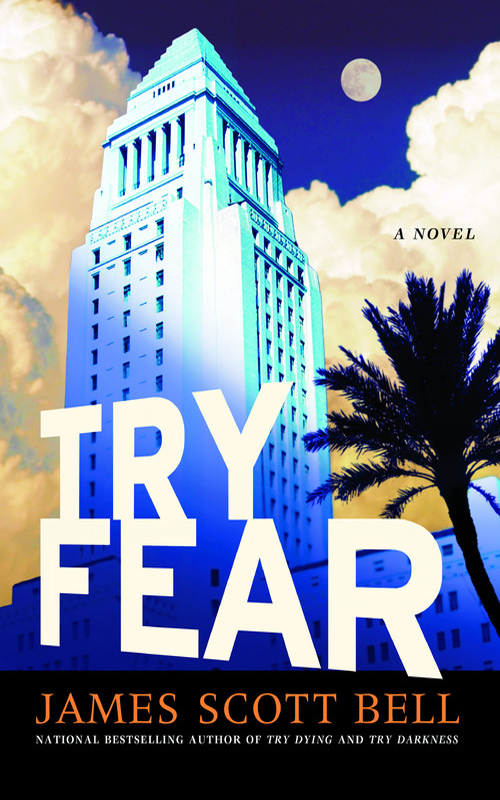

Try Fear

Authors: James Scott Bell

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are

used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright © 2009 by James Scott Bell

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Center Street

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

Center Street is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Center Street name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group,

Inc.

First eBook Edition: July 2009

ISBN: 978-1-599-95310-6

Contents

Also by James Scott Bell

Try Dying

Try Darkness

Available from Center Street wherever books are sold.

My memories of growing up in L.A. come to me mostly in black and white. I see myself as a kid stepping through an episode

of

Perry Mason.

That’s because my dad was an L.A. criminal lawyer, and I remember downtown as being made up of white, sun-bleached buildings,

hot in the summer sun. When I first rode Angels Flight with Dad—I was six, and Dad was involved with a grassroots movement

to save the venerable L.A. landmark, a movement that was ultimately successful—it was to the top of the Bunker Hill from

Criss Cross,

the Burt Lancaster noir classic (a black-and-white film, of course). And when I recall first seeing my dad in court, it was

in the days of the fedora, which TV shows never depicted in living color.

There were a few things about Dad that remain “black and white,” in symbolic terms, too. Dad did not tolerate racism. He had

played baseball at UCLA with Jackie Robinson, was even his roommate on road trips, and as a defender of poor clients brooked

no color barriers when it came to justice. He taught me to think the same way, and made me want to become a trial lawyer like

him. So I did. And even got to work with him, as his office mate, in the last few years of his life.

And so this book is dedicated to a great L.A. lawyer and a great man—my dad, Arthur S. Bell, Jr.

The author is greatly indebted to the following for their exceedingly valuable help in the preparation of this book and series:

Cindy Bell, Christina Boys, Manuel Muñoz, Leah Tracosas, Karen Thompson, Al Menaster, Gina Laughney, Rene Gutteridge, Ellen

Tarver, Michael J. Kennedy, Sgt. Mike Sayre, LAPD, Capt. Tom Brascia, LAPD, and Special Agent Michael Yoder, FBI.

Fear at my heart, as at a cup,

My lifeblood seemed to sip.

—Coleridge

T

HE COPS NABBED

Santa Claus at the corner of Hollywood and Gower. He was driving a silver Camaro and wearing a purple G-string and a red

Santa hat. And nothing else on that warm December night.

According to his driver’s license his name was Carl Richess, a thirty-three-year-old from West Hollywood.

But he insisted he was the one, the only, Santa Claus. He said he could prove it, too. He pointed repeatedly to his hat.

The police officer who initiated the stop—for not wearing a seat belt—mentioned the Santa hat in his report, and the G-string.

Also the open, nearly empty bottle of Jose Cuervo Gold on the seat next to the jolly elf.

After noting red eyes, slurred speech, and the odor of an alcoholic beverage, the officer ordered Richess out of his car for

field sobriety tests.

Richess protested that he was late, that his reindeer needed to be fed. He said this even as he was failing the heel-to-toe

and lateral gaze nystagmus tests.

He loudly screamed the same thing at Hollywood station, where they had him blow into the Intoximeter a couple of times. And

again when they cuffed him to a metal rod on one of the wooden benches outside the holding tank. He was still muttering about

reindeer when they booked him into the jail and stuck the six-foot-five, 280-pound would-be Kringle in a cell. They gave him

some old clothes to cover himself.

They took his hat, let him keep the G-string.

Three others shared the community cell with St. Nick—two gangbangers and a Korean street performer who’d been fire-eating

in front of the Pantages Theater. I found out later he set a well-dressed woman’s hair on fire, which is against several city

ordinances.

About the time Father Christmas was being cuffed and stuffed—copspeak for arrested and jailed—I was nursing a Gandhi Latte

at the Ultimate Sip. The Sip is an honest coffee establishment owned and operated by one Barton C. “Pick” McNitt, a former

philosophy professor at Cal State Northridge who went crazy and now pushes caffeine and raises butterflies for funeral ceremonies.

He makes up drinks that have philosophical significance. He is serious about this. He came up with the Gandhi Latte because

his style of foam, he believes, encourages nonviolence in those who drink it.

This has yet to be proven scientifically.

Pick also waxes loud on any subject he deems appropriate for the betterment, or castigation, of mankind. He does not believe

in God. Father Robert Jackson, who everybody calls Father Bob, does. In the middle I sometimes sit, watching a philosophical

Wimbledon.

But on this particular night there was no match, so I was wrestling with the

Dialogues of Plato

. That’s one thing to do if you’re trying to recalibrate your life and figure out what, if anything, it means. At that moment

it was a tie between

not much

and

something just out of reach.

Which is why I was digging hard into the dialogue called

Phaedrus.

And then I got a call from Father Bob.

“There’s a fellow in jail in Hollywood,” he said. “He needs a lawyer.”

“Anyone in jail in Hollywood needs a lawyer,” I said.

“I mean it. His mother called me, very upset.”

“What’s he in for?”

“He told his mother he sort of got arrested for drunk driving and telling the police he was Santa Claus.”

I cleared my throat. “My dear Father, it is illegal to drive drunk, but not to say you are Santa Claus.”

“He was dressed in a Santa hat and, I guess, a G-string. That’s what he told his mother, anyway.”

I put the

Dialogues

down on the table. “Are you sure it’s a lawyer he needs?”

“His mother says he’s been under a lot of strain lately.”

“Does he have money to pay a lawyer?”

“His mother does.”

“I’m reading Plato.”

“She was in tears.”

“I would be, too, if my son got busted in a G-string.”

“Ty, will you go?”

“To see Santa Claus?” I said. “By golly, who wouldn’t?”

LAPD

’S

H

OLLYWOOD STATION

is a squat brick building on Wilcox, south of Sunset, across the street from the appropriately named SOS Bail Bonds. I got

there a little before ten and parked in front. It was a Wednesday night, quiet in Hollywood. Tomorrow the club scene would

start in earnest and fill the weekend.

At the front desk I put my card down and told the desk officer I was there to pick up Richess.

He laughed. “Santa?”

“He’d be the one,” I said.

“Biggest Santa I’ve ever seen,” the officer said. He had short black hair and a pointed chin. His name plate said H

OWSER

.

“Can we cite him out?” I said, meaning Richess wouldn’t have to post bond. I knew the decision would depend on his previous

record, and what he said or did since they popped him.

Howser said, “I’ll be back.” He got up and went into the inner office, leaving me with a kid, maybe eighteen, who was sitting

by the vending machine, head in hands.