Twinkie, Deconstructed (2 page)

Read Twinkie, Deconstructed Online

Authors: Steve Ettlinger

Likewise, several accomplished professionals at several different large companies in the ingredient chain offered help but only on condition of anonymity, seeking to avoid linking their companies with a specific ingredient or with Twinkies in particular. Often, my source was protecting proprietary information. For this reason, I have changed names in several places as a professional courtesy. This book does not reveal any proprietary information about Twinkies’ or other companies’ manufacturing nor who their suppliers are.

Any ingredient manufacturer described here may or may not supply that ingredient to Interstate Bakeries, just as they may or may not supply it to any other bakery. This is true not only because various suppliers try to keep that kind of information quiet (out of respect for their customers, among other reasons) but also because these vendor relationships change constantly. Many ingredient destinations are not traceable, as they are sold to distributors, not directly to the bakeries.

I have made every effort to be technically accurate, but because our food supply is considered vulnerable to terrorists, some location or company details have been omitted upon request. Also, the industry, recipes, and techniques are in constant flux. For these reasons, some generalities have been made. Dozens of industry professionals have reviewed the material presented here, but in the end, I am solely responsible for any errors contained herein.

Twinkie, Deconstructed

CHAPTER 1

“Where Does Polysorbate 60 Come from, Daddy?”

I

t all came to a head as I was sitting at a picnic table near the beach in Connecticut one fine August day, feeding my two little kids ice cream bars and, out of habit, casually reading the ingredient label.

“Whatcha reading, Daddy?” my six-year-old girl asked. “Uh, the ingredient label, honey. It tells us what’s inside your ice cream bar.” Oops. Slippery slope. Glancing back down at it, I realized it was totally incomprehensible and most terms only barely pronounceable.

“So what’s in it, Dad?” asked my son, a big sixth grader, who started reading his own label aloud. “Oooooh—high fructose corn syrup! What’s that? And what’s pol-y-sor-bate six-tee?”

I started to sweat.

And then my sweet little girl (who at that age still thought Daddy knew everything) pitched the zinger: “Where does poly-sor-bate six-tee come from, Daddy?”

It was a moment of truth that every parent recognizes. When you must admit your fallibility to your worshipful children.

“Uhh…umm…I uh…don’t have a clue, honey,” was the rather disappointing—but honest—answer I mustered. Some father I was! I could speak with a fair amount of authority about Greek olives, Spanish clementines, and tuna fish. But when faced with high fructose corn syrup, I was lost.

Being a curious, food-loving guy, I actually began to think about the question more seriously. I’d always wondered what those strange-sounding ingredients were as I read labels purely out of habit, going through the motions without ever understanding or even gaining any knowledge. Then and there, I decided to put an end to the mystery and find out. I had to find the polysorbate…tree or wherever it came from.

Thinking about the origins of food is not new to me. I lived in France for six years and learned how the origin and handling of wine grapes affects how the wine tastes. I visited the actual villages that Beaujolais Villages comes from. I ate at restaurants featuring regional food—not just regional cuisine, but regional

food

. I bought fruits and vegetables, sometimes directly from the farmer at his or her farm. Now I spend most of my summers on the coast of Maine, where I can gather mussels from the nearby shore and cook them for dinner mere hours later, accompanied on occasion by fish (mackerel) we’ve caught and vegetables we’ve harvested or received from a neighbor’s garden.

When you eat mussels or blueberries that you have collected yourself, or a vegetable you or a neighbor has grown, you don’t have to guess where your food came from. You are consuming it as close as possible to the point of origin, reducing processing to an absolute minimum. Eat your own vegetables and fruits raw, and you’ve reduced “processing” to washing. Eating wild raspberries from your own yard as you pick them is about as short a link to a food source as you can get—a luscious treat and the absolute polar opposite of modern processed food. My kids don’t ask me where these berries come from—they can see for themselves. At the other extreme, the point of processed food is to have no direct link to a place, or even to time. Processed food is meant to be national or even international, and the longer it remains ready for consumption the better. It’s been this way since people started salting, drying, or smoking their food centuries ago.

I know from working as an assistant chef, eating at fine restaurants from time to time, and having done a few food-related books, that intriguing stories accompany many foods, stories that often deal with their origins and processing, like why some beers taste bitter while others taste malty. One glorious night a number of years ago, I was treated to a custom tasting menu by Gray Kunz, one of the best chefs in the world, at his legendary four-star restaurant, Lespinasse, in anticipation of a book project we were contemplating. One dish featured a mysterious, red, tart sauce, and in order to explain what it was made of, Chef Kunz sent out a tuxedoed waiter carrying an immense silver platter lined with sumptuous white linen upon which gently rested a little branch full of red fruit. “Mr. Kunz wanted you to see the source of this sauce—rose hips,” the waiter explained.

That fateful day on the beach with my kids inspired me to do the same for Red No. 40, polysorbate 60, and mono and diglycerides. However, since I lack tuxedoed waiters on my staff, I wrote this book.

I can picture the rose hip bush whenever I see the ingredient listed somewhere, even on a jar of vitamin C (it’s a great natural source). And I can tell you how and where mussels grow, and why the wines of Burgundy or the olive oils of Italy are different from those of Spain. A few years ago, I had absolutely no clue where most of the commonly used natural and artificial ingredients come from, how they are processed, how we came to think of using them in food, or what they do.

Now, I do.

Instead of merely listing, in encyclopedic form, the thousands of foods and food additives that appear in the ingredient labels on products on our grocery store shelves, it seemed to make more sense to try to find a food product that embodied a number of them to serve as a prism through which to address the subject. I wanted to find a familiar food product, or even an iconic one, that many people would recognize and likely would have eaten at some point in their lives. Some kind of bread? Instant soup? Salad dressing? Yoo-hoo

®

Chocolate Drink? All boasted long ingredient lists filled with compounds I didn’t understand, but then I hit upon the one product that truly filled the bill. The übericonic food product, the archetype of all processed foods, the rare food to become part of popular culture (proof: it was included in the Millennium Time Capsule by President Clinton): Twinkies

®

.

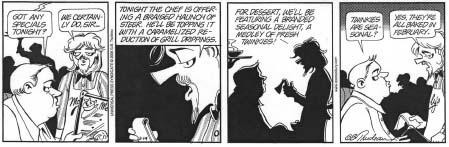

Twinkies’ ingredient list was long enough to include a good variety of additives, including my two top targets, polysorbate 60 and high fructose corn syrup. I also liked the idea of Twinkies because, along the way, I could explore some of the outlandish myths surrounding them. Twinkies are, according to urban legend, so full of chemicals that they will last, even exposed on a roof, for twenty-five years, and take seven years to digest. Some myths claim that they are no longer freshly baked—rather, that they were all baked decades ago—nor do they contain any actual food in them, but are the result of assorted chemical reactions. Or, as a character in a February 14, 2006,

Doonesbury

comic strip stated, baked only every February. I guessed it would be fun to see if there was any truth to these intriguing scenarios, all the while uncovering just what Twinkies are made of.

DOONESBURY

DOONESBURY © 2006 G. B. Trudeau. Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL PRESS SYNDICATE. All rights reserved.

It is not clear why Twinkies may have attracted more attention than any similar snack cake. Other snack cakes use pretty much the same ingredients and strive for a similarly long or even longer shelf life—somewhere, it turns out, around twenty-five days (not years). Is it because they are blond, and denigrating blonds is another old American tradition? Is it jealousy, because they are so famous that even Archie Bunker, the main character on one of the longest-running, most popular TV shows in history (

All in the Family

) took one to lunch every day? Or does it stem from the fascination with the Twinkie’s notoriety, further enshrined in the public consciousness when the innocent snack cake became unfairly ensnared in lurid headlines during the 1979 murder trial of former San Francisco City supervisor Dan White? A doctor testified that White, a normally health-conscious man, was evidently depressed because he had begun eating sugar-laden junk food. In fact, there actually was no direct link with Twinkies—it was the press that erroneously dubbed it the “Twinkie defense.”

Hostess’s own CupCake is actually the bestselling snack cake in history, and there are plenty of competitors just as loaded with sugar and oil that sell, in the aggregate, even more: Little Debbie

®

, Hostess’s main competitor, puts out a long roster of sweet treats such as the aforementioned but less engagingly named Golden Cremes, and there are Ho Hos

®

, DingDongs

®

, Suzy Q’s

®

, Devil Cremes

®

, Kreme Filled Krimpets

®

, among many other creme-filled snack cakes, but none have the allure of Twinkies. Even professional bakers casually refer to all small cakes as “Twinkies.” Now

that’s

an icon.

Because so many of us are disposed to believe the myths surrounding Twinkies, attempting to find the truth added even more intrigue to the investigation. The myths tie right in with the more mundane challenges posed to the bakers of such cakes: keeping the moisture balanced between the cake and the filling while it sits on a store shelf, mixing batters that can stand up to the rigors of mass production, and keeping the price low.

And so I chose the Twinkie as the vehicle for this wild trip through ingredient land—a voyage of discovery of modern food technology. The Twinkie ingredient list, printed on every package, provides the narrative structure.

1

The chapters essentially mirror the label, the ingredients in descending order of prominence, with the exception of the multiple corn and soy ingredients, which are covered in the same chapters because of their common sources and processing. Full of astonishing surprises, like how carbon monoxide plays a key role in making food additives, this journey—my journey—is the story of making convenience food, guided by science and commerce, just like the history of Twinkies themselves.

While the drive to make better food goes back to the dawn of humanity, the drive to create Twinkies started during the Great Depression, near Chicago. Back in 1930, Charles Dewar, a vice president at Continental Bakeries, bakers of Wonder

®

Bread and a variety of cakes, came up with a way to use the idle baking pans for Hostess’s Little Shortbread Fingers, a summer strawberry treat, during their off-season. His idea, sponge cake with a creamy filling, was inexpensive enough that two cakes could sell for a nickel. Inspired by a billboard advertising “Twinkle-Toe” shoes that he passed en route to a meeting to promote his new idea, Dewar dubbed the snack cake “Twinkies. The best darn-tootin’ idea I ever had!” he is oft quoted as saying (he was widely interviewed for the cake’s fiftieth anniversary in 1980). But he would soon learn that even the best darn-tootin’ ideas can be fundamentally flawed.

The shelf life of the original Twinkie—two, possibly three days—posed a huge problem, a fact that dogged Dewar, according to his family. In order to maintain freshness, he had his sales reps remove unsold cakes every few days, but this was costly and inefficient. His ingredient options were also quite limited: the cake was similar to the homemade kind, as far as I can tell (no written history exists), using whole eggs for emulsifiers and lard for shortening (plus flour, water, and salt). Still, Twinkies were instantly and hugely popular, and Dewar credited this focus on freshness to his product’s success. The challenge was to find a way to keep the product on the shelves longer while reducing the number of trips the salesmen (and they were all men back then) had to make to each store. With consumer products like these, shelf life is almost always a primary consideration. Even today, food scientists generally agree that aside from the overriding need to keep costs to a minimum, shelf life (cake or bread staling) is the first problem to solve. (The rather unpalatable problem of leaking moisture and fat run a close second.)