Tyrant (28 page)

Authors: Valerio Massimo Manfredi

Once again, Dionysius’s sweeping eloquence had the desired effect, and his order of the day was approved. He also succeeded in having himself named autocrator, or sole commander, a position which gave him nearly absolute power.

The Italian allies finally arrived, accompanied by Philistus. Dionysius felt greatly encouraged, and certain now that he could win, despite the news arriving from Gela which described the city as being on her last legs, incapable of resisting much longer. But Dionysius was not thinking of the military campaign alone.

Convinced as he was that his power must be consolidated at any cost, he delayed taking action until his friends were successfully installed in the key roles of the State and in all the centres of power.

Still not content, before leaving he persuaded the Assembly to double the salaries of his mercenaries, producing evidence that Himilco had infiltrated paid assassins into the city with the aim of having him murdered. By the time he was finally ready to move, it was the end of the summer.

His army boasted nearly thirty thousand Sicilian Greeks, of whom twenty thousand were Syracusans. They were joined by fifteen thousand Italian Greeks and five thousand mercenaries. The cavalry, composed almost completely of aristocrats, counted a couple of thousand equipped with the finest gear money could buy.

When the confederate army came within sight of Gela, the cheering from the walls was so loud that it reached the Carthaginians’ fortified camp. Dionysius entered the city on horseback, his armour blazing and his crested helmet low over his forehead, as the crowd screamed with joy, parting to let him pass. Behind him were his select troops, marching with a cadenced step, covered with bronze and iron, carrying big shields decorated with fantastic monsters: gorgons, dragons, hydras and sea serpents. A triskelion, the symbol of Sicily, stood out on Dionysius’s shield of shining silver.

And yet, even amidst all the applause and acclamation, many in the crowd could not help but think of the enemy army camped outside, towards the west: unceasingly victorious, inexorable, implacable. They had uprooted and destroyed one community after another, and neither men nor gods had ever been able to stop them.

Dionysius held council that same evening alongside the Geloan generals, some of whom were haughty, presumptuous noblemen, and he immediately met with difficulty. After their initial euphoria, they remembered that they had already seen that arrogant young man the previous winter, and they couldn’t believe that he held the supreme command of such an army. They felt, on the contrary, that the direction of the war should be shared equally, and decisions made collectively.

Leptines took care of the matter personally, doing away with four out of seven, the most stubborn, in less than eight days. He spread the word that they had deserted and gone over to the enemy. Their property and goods were confiscated and Dionysius used the money to pay Dexippus’s mercenaries, who were considerably in arrears of their salaries. He detested the man and considered him incompetent, but at the moment he had no choice; he needed all the help he could get.

Dionysius called a War Council seven days later. Leptines, Heloris, Iolaus, Biton and Doricus were present, along with the three Geloan officers and two Italians, the cavalry commander, Dexippus and even Philistus, admitted as councillor to the commander-in-chief. They met on the highest tower of the walls, from which they could view the entire city, the inland region, the coastline and the Carthaginian camp.

‘My plan is perfect,’ Dionysius started. ‘I’ve been studying it for months. It’s all engraved in my mind: every move, every phase, every detail of the action.

‘Now we’re on difficult ground here, because the city is stretched out on this hill parallel to the sea; Himilco was very astute to set up camp so close. It doesn’t leave us much space to manoeuvre. If I had commanded the army here in Gela, I would have made sure to occupy that land a long time ago, but what’s done is done, and there’s no sense laying blame now.

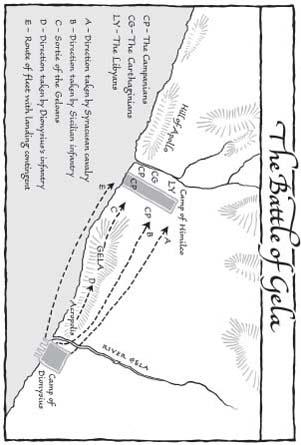

‘You’ll notice that the Carthaginian camp is unfortified on the seaward flank: they’re obviously not expecting a threat to come from there, and it is from there that destiny will strike. We’ll make the first move. Heloris will lead the Sicilians, flanked by the cavalry; they’ll approach from the north shortly after dawn and will immediately draw up in fighting order. Himilco will imagine that we are seeking a decisive frontal battle as Daphnaeus did at Acragas, and will send ahead the Libyan heavy infantry, who will have to fight with the morning sun in their eyes. But at the very same time, the Italians will be attacking from along the sea; they will assault the entrenched camp at the one point in which it isn’t defended . . .’

‘How’s that?’ asked one of the Geloan generals. ‘There’s not enough space to put through a contingent that would be numerous enough to storm the camp. They would have to advance in single file, and when the first are ready to launch the attack, the others will be too far behind.’

Dionysius smiled. ‘They’ll be landing from the sea, all at once. The fleet, concealed behind the hill, will advance until it’s very close to the shore and will disembark five battalions. They’ll wait on that wide clearing you see down there, hidden from the enemy’s sight, until they receive the signal that I myself will give from the western gate: a red cloth, raised and lowered three times. In the meantime, I will have crossed the city from east to west at the head of my select troops and the mercenaries. At this point Heloris, leading the bulk of our troops, will send ahead the cavalry in a converging manoeuvre. Doricus and Iolaus will back him up.

‘Himilco will be forced to split up his forces to face the double threat: Heloris from the north and the Italians from the south. That will be my moment. I will be at the western gate, ready to launch the attack. I’ll plough into the enemy lines with my assault troops and skirmishers, and the Geloan heavy infantry will come up from behind to support our assault.

‘Heloris’s cavalry will be circling around the Carthaginian contingent out on the field, while his heavy infantry, led by Biton and Iolaus, are engaging them frontally. In less than an hour, the joint manoeuvres of my troops and of the Italian allies will have won the upper hand over the camp’s defenders. Himilco will be crushed between my contingent – united with the Geloans and the Italians – and Heloris’s forces. There will be no way out.

‘Spare those who surrender en masse; we can sell them to pay off some of the war expenses. The Carthaginian officers will be executed immediately, without torture. We’ll take in the mercenaries if they decide to desert. I want Himilco alive, if possible. If there’s someone here who feels differently, please speak up. Good advice is always welcome.’

No one spoke. The audacity of the plan had taken them all by surprise and no one seemed to have any objections. It was all so clear, the movements on the ground so evident, the various divisions so perfectly coordinated.

‘I have a question,’ said Dexippus all at once.

‘Speak,’ replied Dionysius.

‘Why are you starting off from the eastern side of Gela with your contingent? You’ll be forced to cross the entire city to reach the western gate from where you plan to attack.’

‘If I moved from any other direction, I’d be seen. Mine will be the final hammer blow. I’ll come out of the Acragantine Gate like an actor emerging from behind the stage and then the show will begin! What do you say?’

Several interminable moments of silence followed instead of the acclamation which Dionysius had expected, but then a Locrian officer named Cleonimus said: ‘Brilliant. Worthy of a great strategist. Who did you learn from,

hegemon

?’

‘From a master. My wife’s father, Hermocrates. And from the mistakes of others.’

‘In any case,’ replied Cleonimus, ‘we’ll still need luck. Let’s not forget that at Acragas we’d already won.’

Philistus went to visit him late that night. ‘Worried?’ he asked.

‘No. We’ll triumph.’

‘I hope so.’

‘And yet . . .’

‘And yet you don’t feel right and you can’t get to sleep. Do you know why? Because it’s your turn now. The other commanders always had some excuse: limited powers, quarrelsome staff officers, internal dissent . . . You have full powers and the greatest army ever assembled in Sicily in at least fifty years. If you do lose, it will be your fault alone, and this is what frightens you.’

‘I won’t lose.’

‘That’s what we all hope. Your plan is very interesting.’

‘Interesting? It’s a masterpiece of strategic art.’

‘Yes, but it has a defect.’

‘What?’

‘It’s like a table game. On the battlefield things will be different; the unexpected always comes up. Linking the forces, enemy response, timing . . . Timing, above all. How will you manage to coordinate the manoeuvres of a military initiative on the battlefield, a contingent to be disembarked, a citizens’ army making a sortie and a battalion of assault troops which has to cross the entire city?’

Dionysius smirked. ‘Another armchair strategist! I didn’t know you were such an expert on the ways of war! It will work, I’m telling you. I’ve already arranged for all the signalling points and for dispatch riders as well. It has to work.’

Dionysius raised his eyes to the mask of Gorgon displayed on the eastern tympanum of the Temple of Athena Lindos and leaned over the battlements to scan the countryside to the north of the city: Heloris’s army was advancing with the Sicilian contingent, twenty battalions spread out over a wide front in two long lines. He could even make out the commander, riding ahead of all the rest.