Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (12 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Out at the center-field kids play area, tikes line up with their kid siblings in tow, ready to get the little guys (and gals) wet. As parents, we think that on a hot day a ballpark dunk tank is a fun diversion. In April or May, not so much. But the kiddos will want to partake no matter what the temp is, so moms and dads should be sure to bring a change of clothes to the park.

Josh:

Heather and I bring about three changes wherever we go.

Kevin:

Well, that will end once Spencer is out of diapers.

Josh:

Oh, not for Spencer. For me. I hate getting sweaty.

Kevin:

I’ll file that as Josh Pahigian eccentricity number 103.

Our friend Joe spent half an inning circling the first level concourse looking for a Bank of America ATM. But he only

encountered one Citibank cash dispenser after another. Finally, it dawned on him that he was at Citi Field and he resigned himself to paying the higher withdrawal charge his bank assigned to transactions on Citi machines.

Cyber Super-Fans

- Mets Merized

- 213 Miles from Shea

- Mets Are Better than Sex

Wearing a Mets jersey that bears No. 15 and the name “Cow-Bell Man” across the back, lifelong Mets fanatic Eddie Boison roams the upper levels of Citi Field with his trusty cowbell in hand, just as he used to do at Shea Stadium. Trust us, you’ll hear him coming.

Josh:

I didn’t know there were cattle farms in Queens.

Cow-Bell Man:

Ding, ding, ding.

Josh:

Do you herd

dairy

cows or

beef

cows?

Cow-Bell Man:

Ding, ding, ding.

Josh:

Because I really like steak.

Kevin:

We’ll get you a Cowboy Steak in Texas, Josh. Let the poor man be.

What Cow-Bell Man is to the Mets and their fans, “Howling Hilda” Chester was to the Brooklyn Dodgers. She worked part-time filling paper bags with peanuts, then reported to the bleachers where she would sit in a flowered dress and bang on a frying pan all game with a big iron ladle. On special occasions, she would lead the Bleacher Bums through the Ebbets Field aisles in a long snake dance procession. By the 1930s, she was so well known that Dodgers players presented her with a special cow-bell that she used as a noisemaker until the team left town in the 1950s.

From 1964 through 1981, Mets fan Karl Ehrhardt had his own way of shouting support for and criticism of the home team. He would schlep large homemade signs to Shea Stadium and hold them up. “The Sign Man” was a fixture right behind the third base dugout. The several dozen cleverly

conceived signs he brought to each game were separated by color coded tabs, so that he could hold up the most apropos ones when the events of the game dictated he ought to make his opinion known. Some of his more memorable signs included gems like “Look Ma, No Hands,” which he once held up after an error by Mets shortstop Frank Taveras, “Jose, Can you See,” which he displayed after strikeouts by the oft-whiffing Jose Cardenal, and “There Are No Words,” which he triumphantly hoisted after the Mets got the final out of the 1969 World Series.

Sports in (and around) the City

Elysian Fields

11th Street and Washington Street

Hoboken, New Jersey

Baseball lore offers conflicting stories concerning the sport’s origins. One nugget of folksy wisdom says Abner Doubleday invented baseball back in 1839, while another tall tale crowns Alexander Joy Cartwright the “father of baseball,” pointing to a “first game” at Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey, in 1846. In actuality, neither man invented baseball. Baseball evolved out of English games like cricket and rounders during the first part of the nineteenth century. In the later 1800s, as modern transportation made Americans more mobile, the different versions of the game assimilated into one.

However, the site of Elysian Fields, where Cartwright and his friends played, is considered holy ground by many lovers of the sport. Today, the park has been reduced to a strip of lawn between two lanes of traffic. A monument reads: “On June 19, 1846 the first match game of baseball was played here on the Elysian Fields between the Knickerbockers and the New Yorks. It is generally conceded that until this time the game was not seriously regarded.”

Readers will note that the inscription doesn’t proclaim Hoboken the birthplace of baseball. But that doesn’t mean the Elysian Fields site isn’t worth a visit if you’re a starry-eyed romantic for the game. The field did play a role in the development of baseball’s previously unwritten rules, even if the rules employed for games there bore scant resemblance to the ones we know today.

Cartwright was a bank clerk, who spent the early 1840s playing afternoon games of “base ball” at a vacant lot in Manhattan with other professionals. Then, in 1845 the lot they used was slated for redevelopment. So Cartwright and his friends went looking for a new place to play. They found Elysian Fields, a tree-lined park just across the Hudson River. Cartwright’s newly formed club of “Knickerbockers” rented the field and traveled to it regularly via ferry. And in the winter of 1845–1846, Cartwright scribbled out fourteen rules to characterize the game he and his friends had been playing for years already. He was not inventing the rules, but he was recording them. The “Cartwright rules” said that baseball should be played on a diamond, not a square, that the distance between home plate and second base should measure forty-two paces (which makes for bases approximately seventy-five feet apart), that balls struck outside the baselines should be declared foul, and that runners should be tagged out (as opposed to being struck by thrown balls).

Josh Sold His Red-Sox-Loving Soul for a Dry Shirt

We rolled into town for a day game against the Cardinals at the height of the worst heat wave to besiege New York City in several years. Thermometers read 105 degrees Fahrenheit, and meteorologists reported the heat index had climbed to 112 degrees. We admit to having no flipping idea what the heat index is, but we can attest it was damned hot in the Baked Apple during our visit.

Appropriately, Kevin wore the thinnest Bermuda shirt in his “eclectic” wardrobe. Josh, on the other hand, wore a thick-weave “Ultimate Baseball Road Trip” golf shirt that his thoughtful mother-in-law, Judy Gurrie, had ordered for him at a specialty shirt shop.

As Josh blotted his face with a wad of wet paper towels, Kevin said, “I can’t believe you’re wearing that thick shirt.”

“Even my fingernails are sweating,” Josh replied. “And my wristwatch is all fogged up with condensation.”

“You’re on the fast-track to heat-stroke, my friend,” Kevin quipped, then he said, “This oughta help you along,” and handed Josh a lukewarm cup of Bud Light.

By the time the middle of the fourth arrived, Josh was drenched from head to toe and practically delirious. At just that time, a Citi Field pep-squad guy walked up the stairway to Section 511 where we were sitting. And Josh really let him have it. You see, the young man had an armful of bright orange T-shirts, and as the knowing fans in our section spotted him, they began to cheer. And he began to fire shirts at them. This struck Josh as too bush league a stunt for the biggest big league city of them all. “What is this, an arena football game?” Josh heckled. “Or a New York-Penn League game?”

Everyone else, including Kevin, was standing by now, and waving their arms, in hopes that the T-shirt guy would toss some free Mets garb their way. “Like I’d

ever

wear orange even if it

didn’t

have a Mets logo on front,” Josh jeered. “I wouldn’t wear that crappy color if it was the last shirt on earth and I was marooned at a nudist camp.”

“Pipe down,” Kevin said. “I think you’re delirious. You’re not making any sense.” But practically no one else heard Josh. The others nearby were too preoccupied with trying to get a shirt. Either they were calling for one, or jumping up and down to get the shirt guy’s attention, or leaning and lurching to catch a flying shirt. To his credit, the shirt guy had unleashed a barrage of a half-dozen shirts within about ten seconds of his arrival at the end of the aisle.

But he still had one more to throw, and wouldn’t you know, it sailed right through the outstretched arms of the attractive, slightly inebriated woman a row in front of us, and into Josh’s lap. Josh instinctively wrapped it up as if it were a coveted milestone home run ball, and started to throw his elbows around just in case anyone should try to yank it away from him.

“Ha!” Kevin cried, lowering himself into his seat. “You didn’t even want a shirt and you wound up with … Hey, what are you doing?”

Before Kevin could finish his thought, Josh had stripped the sweat-soaked “Ultimate Baseball Road Trip” shirt from his body, and had slipped into the bright orange Mets shirt.

“What are you doing? You hate the Mets,” Kevin said.

“A dry shirt is a dry shirt,” Josh replied.

“But you said you wouldn’t wear a Mets shirt if it was the last one on earth.”

“It was all part of my strategy,” Josh replied.

“Your strategy?”

“I knew he would huck one at me if I tossed a few barbs his way,” Josh explained.

“Um, I’m pretty sure he was throwing it to the cute girl in front of us,” Kevin said. “You practically wrestled it away from her.”

“You can believe what you want,” Josh said. “But I happen to be wearing the driest shirt in Section 511.”

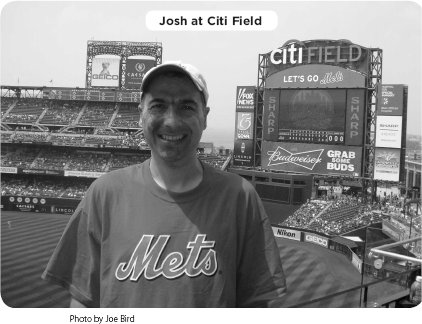

Kevin shook his head in disbelief. “It’s true what they say about a trip to the ballpark,” he said. “You never know when you’re gonna see something you’ve never seen before. And I’m taking a picture of this because I’m pretty sure I’m never gonna see it again.”

NEW YORK YANKEES,

NEW YORK YANKEES,YANKEE STADIUM

The House That George Built

T

HE

B

RONX

, N

EW

Y

ORK

10 MILES TO CITI FIELD

105 MILES TO PHILADELPHIA

200 MILES TO BALTIMORE

205 MILES TO BOSTON

W

hen the original Yankee Stadium opened in 1923 at a hitherto unheard of construction cost of $2.5 million, the man credited with providing the Pinstripes with the popularity, pizzazz, and not least the bankroll, to embark upon such an ambitious venture as the world’s first triple-decked baseball stadium took a good look around and commented, “Nice little yard.” Babe Ruth was no doubt speaking ironically when he gave the Stadium that understated appraisal. Clearly, he understood the import of the Stadium’s arrival. And the Yankees and their fans did too. Their team already boasted the game’s brightest star and a steadily increasing number of rooters, and now it had the grandest facility the game had yet known. Appropriately, Ruth and his teammates capped Yankee Stadium’s inaugural season by winning the club’s first World Championship that fall.

Fast-forward nine decades to another grand opening in the Bronx, and this time the expectations and fanfare surrounding the latest Yankee Stadium were even greater. In the midst of America’s worst economic downturn since the Great Depression, baseball’s most successful team was introducing a five-level replacement for its hugely popular “House that Ruth Built.” What’s more, the new park carried an unimaginable price tag of $1.5 billion. That’s right,

billion

with a “B.” And that figure doesn’t even include the land acquisition costs for the stadium site, neighborhood infrastructure improvements, the construction of community ball fields to replace the ones that had been razed to make way for the new stadium, and the demolition and removal of the old stadium. All told, the new Yankee Stadium cost more than $2.3 billion. To put this number in perspective, prior to the opening of the new Yankee palace and the concurrent opening of the Mets’ Citi Field, the most expensive baseball facility ever built had been Toronto’s Rogers Centre, which cost $570 million back in 1989. And Oriole Park at Camden Yards, which is often referred to as the standard bearer of the retro parks we fans love, cost only $110 million to build in 1992.

So it’s fair to say that expectations were sky high for the new baseball grounds in the Bronx, where a front row seat behind the Yankees dugout would go for $2,625 per game. Nonetheless, new Yankee Stadium exceeded even the loftiest of hopes. Yankee captain Derek Jeter was one of the first to admit to being blown away by the new digs. Expressing his thoughts a bit more artfully than the starry-eyed Ruth had upon the unveiling of the previous Bronx behemoth, on the date of the home opener in 2009 Jeter admitted, “It’s a lot better than I think anyone even expected. You know, I tried to come here, not ask too many questions about it, just wanted to experience it for the first time. But this is—it’s pretty unbelievable.”

Yankee president Randy Levine, meanwhile, explained that evoking such a jaw-dropping reaction from players and fans alike had been in the Yankees’ designs from the very start because that’s the way Yankee owner George Steinbrenner had wanted it. “It’s always George’s philosophy,” Levine explained. “This is the Yankees; everything has to be done first-rate. We wanted … to create a stadium that, when you go in, there’s a ‘wow’ factor.”

In this regard—and countless others—the Yankees clearly succeeded. If you’ve gotten to know your two humble writers in the course of reading this book or its previous edition, you know that we are by no means Yankee apologists. We both root for other American League teams and through the years have come to view the Yankees about as fondly as the mildew in our bathroom grout, or the bloated wood ticks Josh yanks from the manes of his golden labs Maddie and Cooper. Heck, we co-authored a book together titled

Why I Hate the Yankees

a few years back. We want to retch every time we see a pinstriped suit, let alone a pinstriped baseball uniform. We thought the late Mr. Steinbrenner was an arrogant bully. We think most Yankee players are mercenary front-runners. And we have scrupulously shunned Derek Jeter from our fantasy teams

throughout his entire career, even when he was one of the best shortstops in the game. Sorry, Derek, no Yankees welcome here.

Kevin:

The Red Sox aren’t much better these days.

Josh:

Oh, come on. That’s just sour grapes talking.

Kevin:

Boston might as well be wearing red pinstripes.

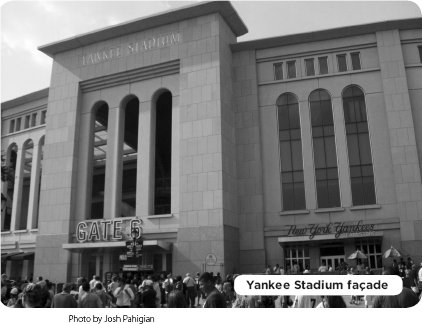

And yet, we have to give the Yankees their due. We have to tip our caps to King George. We have to agree with the sentiments of Jeter and Levine. We exited the 4 train expecting to be blown away by the most expensive sports venue ever known to man. And yet we still had to admit Yankee Stadium exceeded our preconceptions in practically every regard. It’s bigger, more luxurious, and more beautiful than we could have imagined. We were gaping from the moment we stepped onto the plaza outside Gate 4 and gazed up at the regal seven-story façade made of white Indiana limestone, granite, and concrete, with tall narrow arches aplenty. Truly, there’s no other stadium that beams with such palatial majesty. No other stadium makes such a grand first impression. Sure, the train station at Minute Maid Park in Houston serves as a historic gateway to the baseball grounds; the rotunda at Citi Field is a crisp, clean, and beautiful structure; and the Eutaw Street entrance of Oriole Park welcomes fans to a festive place for pregame revelry. But there isn’t another ballpark in baseball that welcomes fans to an interior space behind the first level concourse and seats like Yankee Stadium does.

The appropriately named Great Hall is a wide and exceedingly high ceilinged (we’re talking the full seven stories) room just inside the gates. It provides space for vendors, for the largest of the stadium’s six apparel stores, for a bar and two restaurants, for a giant high-definition video screen, and for massive vertical banners that honor some of the Yankees’ favorite players. The old players like Yogi Berra are rendered in black-and-white photographs, while more recent “greats” like Dave Winfield and Paul O’Neill appear in color. And all of this appears before fans even make their way to the ramps that lead to the first level concourse, which allows fans to walk around the entire lower bowl.

Now, rambling fans are already well acquainted with the concept of a walk-around or 360-degree concourse. Designed to provide a view of the game to strollers seeking concessions or heading to the john, these have become a staple of the ballpark experience during the retro renaissance. Usually, however, new parks unveil

first levels

that employ this design approach. At Yankee Stadium, the concept has been extended two steps further. Not only does the 100 Level have a concourse with a view, but the 200 and 300 Levels do too. This is just one of many best practices the Yankees implemented with the aid of the most renowned ballpark architects in history—the good folks at Populous (previously known as HOK Sport). Another concept the Yankees have embraced to the hilt is the in-stadium bar or restaurant. Such on-site watering holes are popular in the modern day and most parks are proud to boast one or two on their grounds. The Yankees offer no fewer than eight by our count, including the ritzy and critically acclaimed NYY Steak; the members-only Mohegan Sun Sports Bar, the tinted windows of which double as the batter’s eye in center; a Hard Rock Café; the Jim Beam Suite; Tommy Bahama’s cocktail bar in the Great Hall; and the Malibu Roof Deck.

Another modern innovation is the prevalence of flat-screen TVs throughout our modern parks and their concourses, so strolling fans can keep an eye on the game. And the Yankees have outfitted Yankee Stadium with an amazing 1,200 screens. The biggest one is the video board in straightaway center that is the third largest board in all of baseball. It measures 101 feet across by 59 feet high. Only the boards in Kansas City and Houston are larger.

Kevin:

Kansas City trumps New York! Who knew?

Josh:

But the Royals still gave Roger Maris to the Yanks.

Yankee Stadium also offers a comprehensive team museum where all of the World Series trophies are on display, and statues of Berra and Don Larsen commemorate Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series. Another prime attraction away from the field itself is Monument Park, which has been transplanted from the old yard and resurrected in center. To say it draws huge pregame crowds would be an understatement of monumental proportions. There is also a timeline spanning the entire first level concourse that pays tribute to every championship team in the Yankees’ grand history. And there are two baseball collectibles stores. And there’s a store just for women. And there’s a special store for Monument Park memorabilia. Serious shoppers could spend an entire afternoon just eating and browsing the stores at Yankee Stadium.

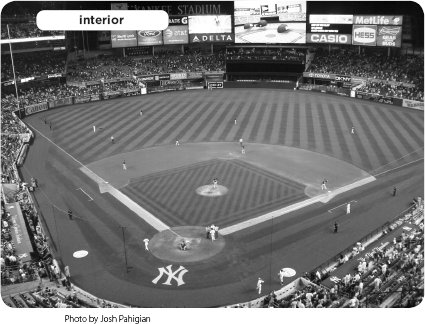

As for the field, its dimensions replicate the old Yankee Stadium’s as it existed in its final state after many modifications through the years. “Death Valley” in left-center is not as vast as it was in Ruth’s day, but the fence still measures a deeper-than-usual 399 feet from the plate. Down the line in right, the foul pole stands 314 feet from the plate, just as it did at the old Yankee Stadium. But the right-field fence angles toward center in a straighter course than it did at the old yard, making the actual distance from home plate to the seats in right and right-center considerably less than it was previously. Perhaps this is why left-handed batters have yanked long balls with such alarming regularity since the new Yankee Stadium’s opening.

The stadium’s trademark feature is its decorative white filigree or frieze, which rings the entire rim of the upper deck. This slatted white steel, which looks a bit like an inverted picket fence, spanned only the outfield portion of the Yankee Stadium at which most of us remember watching games. But old-timers will recall that prior to the renovation of the old Yankee Stadium in the mid-1970s the filigree had rimmed the entire top of the upper deck, just as it does now at new Yankee Stadium. The stadium lights are mounted directly atop this white adornment. You’ll notice there are no light towers at Yankee Stadium, nor are there light banks. There’s just a solid ring of light atop this ornate white metalwork.

In this age when folks seem to swoon over a skyline view at the old ballgame, Yankee Stadium delivers this too … sort of. The skyline in right showcases several weathered brown apartment buildings on Walton and Gerard Avenue that might cynically be described as “tenements.” Unfortunately, the designers of the park couldn’t position the outfield toward Manhattan because then batters would have faced a setting sun. There is, however, a view of the tall, beautiful buildings of the Big Apple, for those who seek it. A visit to the Malibu Roof Deck on the 300 Level showcases the skyscrapers of midtown out of the back of the stadium.

Kevin:

Wow. There’s a nice breeze here too.