Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (136 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

The nationwide ballpark phenomenon that has seen fans spell out “YMCA” with their bodies as they sing along with The Village People began in Oakland when construction workers were building Mount Davis. One day the working men started dressing like the Village People and using their bodies to spell out letters and the fans followed their lead.

Josh:

So not only do we have those workers to thank for Mount Davis but for that annoying song too?

Kevin:

At least they didn’t start the wave.

Sports in the City

The Oakland Public League

Oakland attracted much of its African American population during and after World War II because of the jobs available in the shipyards. And because baseball was king back then, the Oakland Public League became a hotbed of talent. Future ballplayers who weren’t necessarily born within the Oakland city limits but came of age there during their high school years form an impressive list that includes Rickey Henderson, Joe Morgan, Dennis Eckersley, Dave Stewart, Ruppert Jones, Gary Pettis, Willie McGee, Lloyd Moseby, Kenny Williams, Claudell Washington, Frank Robinson, Curt Flood, Vada Pinson, Jimmy Rollins, and Dontrelle Willis.

The decline of baseball in the inner city has given way to basketball being the new pastime of choice on the urban scene. Oakland has adopted this tradition too, sending such locals as Bill Russell, Gary Payton, and Jason Kidd to the Association.

If you look into the dugouts you’ll see advertising wallpapered all over the place. And you’ll see company logos smothering the outfield walls and facades too. The ads are everywhere.

Kevin:

At least they bring some color to all this concrete.

Josh:

And ballpark ads are as ancient as the game itself. Back in the 1940s Fenway’s Green Monster was covered.

Kevin:

Not with ads for virus protection software.

Josh:

C’mon. Virus protection and baseball go together like hotdogs and ketchup.

Kevin:

You mean mustard.

Josh:

Whatever.

Josh Went Native

Our seats were on the second deck, and not in the good part. So we decided to walk around and see if we could do a little creative upgrading. We wound up down the left-field line quite a ways, but with an improved view over where we started.

“Those drums are really distracting,” Josh said.

“But I kinda wish Seattle had a tradition like that,” Kevin said.

“Well that kind of thing would never fly in Boston, I’ll tell ya that.”

“You’re right. Way too uptight in Beantown.”

“It’s not that we’re uptight,” replied Josh, “we just have better taste.”

“All uptight people always claim they are acting uptight in the name of good taste,” said Kevin.

We continued watching the game, which turned “out to be quite a pitchers” battle. Gio Gonzalez was on the mound against the Royals, and he was spinning a beauty. He had only given up one hit through four, but the score remained tied at zero. But Josh was distracted by the drummers, fidgeting in his seat. And because Josh was distracted, Kevin was distracted.

“Don’t those guys know anything besides Let’s Go A’s? Bap-Bap-Bap?”

“Who are you, a long lost Steinbrenner? Let the kids drum if it makes ’em happy.”

But Josh’s head kept turning from the game and over to the drumming.

“Hold my binocs. I’m going to get something to drink,” he said at last. “This pretzel’s making me thirsty.”

“Bring me a beer,” Kevin shouted after Josh as he walked up the aisle.

After half an hour, Kevin started to wonder about his friend. “Probably never get my beer,” he muttered.

By the time the seventh inning stretch rolled around, Kevin, who is not one prone to worry about much of anything, began to get concerned about Josh. As the locals sat back down after a rousing rendition of YMCA, Kevin stood up, raised Josh’s binoculars, and had a look around the Coliseum. He searched the ballpark over, but he couldn’t locate Josh. Eventually, he sat back down.

Finally Kevin decided to get himself a beer before last call, and at the end of the inning he headed to the top of the concourse. The beer stand behind the section didn’t sell Pyramid, so Kevin moved on until he found one that did. He wound up near the foul pole where he stopped to watch the game as he sipped the foam off his beverage. The A’s had begun to pull away, opening a four run lead.

Though his eyes were on the game, Kevin caught a glimpse of Josh in his periphery. Josh had not only found a way down into the left-field bleachers, but he was pounding away on a drum like a madman. He stood shirtless above the tom-tom, beating the skins as if his life depended on it. Kevin tried to get down to the section to meet up with his friend. But a security guard stopped him. He could only stand there at the top of the concourse and watch in shock.

After the game Josh met up with Kevin at the original seats, the bad ones on the second level, wearing his Red Sox shirt once again.

“Have fun?” Kevin asked.

“Sure,” Josh said. “I sampled a couple more sausages at Saag’s and checked out the view from the third deck.”

“That’s it?” Kevin asked, knowingly.

“Oh yeah, I tried the macaroni and cheese hotdog too.”

“You didn’t do anything else?”

“I peed twice,” Josh said, growing suspicious.

To his credit, Kevin let the matter drop. He had spied the Mr. Hyde buried somewhere deep within his ordinarily uptight friend but didn’t reveal his new knowledge … until right now!

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS,

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS,AT&T PARK

Restoration of a Winning Tradition

S

AN

F

RANCISCO

, C

ALIFORNIA

17 MILES TO OAKLAND

379 MILES TO LOS ANGELES

753 MILES TO PHOENIX

679 MILES TO SEATTLE

S

an Francisco’s baseball fans seem to have access to their own private genie lately. Not only did they build one of the grandest stadiums in the Grand Old Game, but they managed to break their fifty-six-year drought and win their first World Series since the franchise left New York. Though it was an unlikely band of rag-tags and journeymen that pulled off the seemingly impossible in 2010, that win and playing in a ballpark as majestic and beautiful as AT&T Park have restored the team and its fans to their rightful place in the game—as winners. After all, the franchise has more wins to its name than any team in North American professional sports history. Yes, that includes the Yankees, but the Giants, who formed in 1883, had a bit of a head-start on them, since the Pinstripes didn’t start playing until 1901 and thus rank only eighth on baseball’s all-time wins list. As for the Giants’ recent winning ways … if you didn’t believe in feng shui—the Chinese belief that living somewhere that’s in harmony with heaven and earth improves your fortune—then AT&T Park and the return of the Giants’ winning tradition just might convince you.

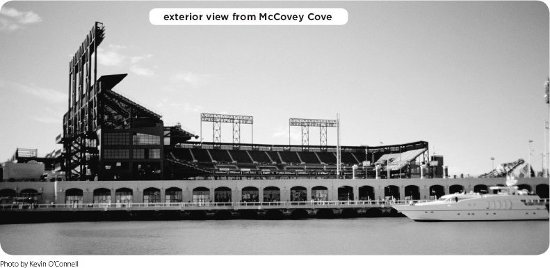

First off, AT&T Park could scarcely be in a better location. Few ballparks in history can boast better views both inside and out than AT&T Park does. Built at the water’s edge on glimmering San Francisco Bay, and part of the formerly aging warehouse district called China Basin, AT&T Park fulfills Giants fans’ vision of a downtown ballpark on the Bay. And better still, this yard is shielded from the bitter evening winds that tormented the Giants and their fans when the team played at Candlestick Park. The ballpark is nearly perfect, and is truly the culmination of Bay Area fans’ most fantastic and idyllic dreams.

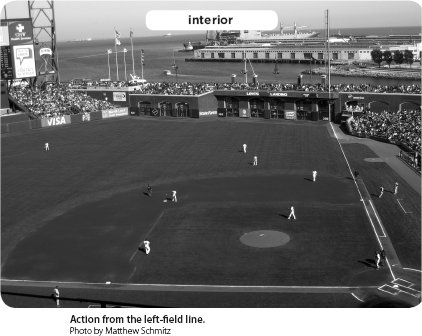

AT&T was designed to fit on a thirteen-acre parcel of industrially zoned land owned by the San Francisco Port Commission, to whom the Giants still pay an annual lease. With the water of the bay just beyond the right-field wall, this ballpark comes by its eccentric short porch in right field (309 feet to the corner) very naturally. There are no quirks for quirks’ sake at AT&T, as have been engineered and manufactured at so many other ballparks of the retro renaissance. Rather, this ballyard was designed—oddities and all—in the same manner as Fenway Park, the Polo Grounds, and all of the clunky but endearing ballparks of old: by building it into the space available. And the result is a gem of a field, with distinctions and idiosyncrasies that are honest, unforced, and far more beautiful than had the quirks been added simply because of some regrettable notion conceived during the post-dome and cookie-cutter eras that they were missing.

Also as a result of the limited available space, the upper-seating structure rises very steeply, getting in as many seats as is reasonably possible. The structure extends down the right-field line to the foul pole on the lowest level, but only three quarters of that distance in the upper deck, angling back obliquely to where it, too, meets the waters of McCovey Cove (so named after Hall of Famer and Giants fan favorite Willie McCovey). The entire seating structure on the left-field side extends to the foul pole and wraps around the outfield as one might expect. The overall impression is that the park would have been built symmetrically if that had been possible, but that things were cut short down the right-field line out of necessity. But the quirks that the space limitations have created in the ballpark have resulted in its distinctive design and local flavor. And who can argue that this park is something special, something unique, something so very San Franciscan?

The story of how the “Miracle on 3rd Street” came to be is as heartwarming to us as the Christmas tale of a similar title. With the Giants faltering throughout the 1970s and 1980s, and playing their games in the cold and clammy Candlestick Park, talk of moving the team to another city would arise every few years. Real estate mogul Bob Lurie bought the team in 1976 specifically to save it from being sold to

a Canadian brewery that intended to move the Giants to Toronto. During his ownership, which lasted until 1993, Lurie would make countless unsuccessful attempts to get a ballpark built downtown, but there was little political will. Finally and reluctantly, Lurie agreed to sell the Giants to a group of investors who planned to move the team to Tampa Bay, the often publicized Holy Grail of baseball relocation destinations. The transaction was nearly complete, but in an eleventh-hour deal a local investment group headed by grocery store magnate Peter Magowan kept the team in San Francisco.

Magowan and his partners knew that the long-term security of the franchise in the city rested on building a downtown ballpark. And so “Proposition B” came before the voting public, which proposed building a ballpark in the China Basin district of downtown San Francisco, which would be the first completely privately funded ballpark in baseball since Dodger Stadium opened in 1962.

Over the next several years, sponsorship agreements were secured with companies that ranged from Anheuser-Busch to Visa and Old Navy, and many others that would eventually help finance the ballpark. Naming rights were purchased by Pacific Bell Telephone and Telegraph Company for $50 million over ten years. Then, Pac Bell was bought by SBC Communications, and so the ballpark was renamed SBC Ballpark in 2004. Just when the ink on the new signage was dry, it all had to come down again, as SBC (Southwestern Bell Company) Communications bought out its parent company AT&T, and changed its name to AT&T, Inc. The newly re-conglomerated AT&T took on the corporate logo of the old, and the ballpark got a new name.

Kevin:

Any of this ringing a bell?

Josh:

Stop phoning in the jokes, please.

In addition, fifteen thousand prime seats were sold on a lifetime basis to thick-walleted fat cats for big money.

Kevin:

It’s a good thing all these corporate sponsorships and seats sold to wealthy dot-com-ers in the nineties. If it were today, the park might not have been built.

Josh:

Yeah, Enron was one of those sponsors.

With the noted firm HOK signed as the architects, San Franciscans felt they were going to get something special in the design of AT&T Park. They had no idea how special. Ground was broken on December 11, 1997. In August 1998 the official address of the ballpark changed from One Willie Mays Plaza to 24 Willie Mays Plaza, in reference to the number worn by the “Say Hey Kid” as a Giant. By the time construction had finished, the ballpark cost $318 million to build.

The first game at the new park pitted the Giants against their archrivals, the Dodgers, on April 11, 2000. Unfortunately for the Giants, the Dodgers won 6–5, but it was an

exciting game as the teams combined for six home runs, setting a record for a ballpark inaugural. Another record, though rather dubious, came when the Giants lost their first six games at their new home. But fan support never faltered, as Giants rooters kept turning out to see the superb new ballpark that sold out every single game of its first season. More than 3.3 million fans visited the park in 2000, and they were rewarded when the Giants captured the National League West title.

Though reviews of the new park’s beauty and setting were glowing from the start, perhaps the most significant improvement fans noticed over Candlestick Park was the weather. AT&T, though located on the very same bay as “the Stick,” is affected far less severely by the notoriously chilly evening winds that besieged fans at the Giants’ former home. Prior to construction, an environmental review process showed that if the ballpark orientation was turned at a certain angle, the wind off the water would be minimized by a staggering degree. Plus the location of China Basin simply has milder weather than Candlestick Point.

These revelations have made all the difference in a city known for its “outdoor air conditioning.” As Mark Twain once commented, “The coldest winter I ever spent, was a summer in San Francisco.” Thankfully technology and environmental awareness have lessened the effects of the wind, cold, and fog that plagued Candlestick. However, after a nice San Francisco summer’s day, it can still be awfully chilly standing on the exterior concourse of AT&T, but inside the ballpark a comfortable environment for baseball awaits. Who says you can’t control the weather? See what we mean when we say genie?

Despite these pleasant developments, since moving into AT&T, the Giants have seen their share of heartbreak as well. In 2002, in a World Series that pitted the Giants of northern California against their cultural and geographic rivals, the Anaheim Angels in the southern part of the state, the Giants were leading the series three games to two entering Game 6. The Giants had just crushed the Angels 16-4 in Game 5, and all was looking up in San Fran. Taking a 5-0 lead into the bottom of the 7th inning, manager Dusty Baker inexplicably took the ball out of pitcher Russ Ortiz’s hands, though Ortiz had been masterful on the mound. Reliever Felix Rodriguez gave up a three-run shot to Scott Spiezio that not only propelled the Angels to a 6-5 victory in Game 6, but also a Game 7 victory to win the World Series the following night. It also propelled Scott Spiezio to an ill-advised musical career with his band Sandfrog.

It was an epic collapse, and one that cost Dusty Baker and many other Giants their jobs.

Kevin:

I watched that game with my good buddy and long-suffering Giants’ fan, Paul Schmitz. After being up by five in the seventh, I think he finally started to believe it was the Giants’ year.

Josh:

You think I don’t know how he feels? Bill Buckner, my friend.

Kevin:

Yeah, well the Sox and the Giants have both since got their World Series. What have the Mariners got, except the two worst seasons of Scott Spiezio’s career?

But there was still more tragedy to be snatched from the jaws of victory for the City by the Bay. Hometown hero Barry Bonds went on to break Hank Aaron’s all-time home run record, posting 762 dingers by 2007. It was a record that nary anyone outside of San Francisco wanted Bonds to break, but break it he did. Bonds hit number 756 to surpass Aaron before an adoring AT&T fan base that didn’t want to believe the rumors of his alleged steroid and HGH use. San Franciscans wanted the moment to be theirs. They wanted their native son to make good. And they wanted it to happen in the ballpark with the short right-field porch that had been built specifically with Bonds’ left handed bat in mind.

And while San Franciscans got what they wanted in the short term, the public opinion on Bonds and his record would continue to sour, until finally, not one team would offer the newly minted HR king a contract. Not one American League team in need of a designated slugger who could surely hit twenty-five HRs and put butts in the seats could find a space on its roster for Bonds. Not even the Tampa Bay Rays, who welcomed admitted juicers Jose Canseco and Manny Ramirez to their roster, would take Bonds.