Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (44 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Since 2010 the fans at the Trop have been really flipping whenever DJ Kitty, aka Button the Cat, appears on the video board. Dressed in his backwards Rays cap and team jersey he spins some vinyl and bops to the beat to inspire the fans and team. In the land of cat walks, this is an appropriate shtick even if it seems a bit derivative of the Angels’ Rally Monkey.

Recognize a familiar voice emanating from the third-base boxes—high-pitched, high-strung, and bubbling with excitement? “Awesome pitch, baby! Awesome!”

That’s right, college basketball guru and local resident Dick Vitale has owned season tickets since the Rays debuted in 1998. And if you think he whoops it up on ESPN, wait until you hear him at the ballpark. In 2010, he was struck in the chest by a foul ball off the bat of Toronto’s Fred Lewis. The injury occurred on the first pitch of the game, but Dicky V. hung in there until the final out. Now that’s what we call a “gamer.”

With an even louder set of pipes than Dicky V., the Happy Heckler of Tampa Bay has also done much to make his presence felt at the Trop through the years. This gentleman, who has season-tickets behind the plate, likes to pick on one opposing player each series. Whenever that player comes to bat, he really lets him have it. Then he more or less quiets down until the player appears again. For the most part his heckling is good natured but he does draw his share of angry stares.

Kevin:

Clearly this guy didn’t get enough attention as a child.

Josh:

Heckling is part of the game. Lighten up.

Kevin:

Afraid he might heckle us next time we visit the Trop?

Josh:

Well … not if we say nice things about him.

Hulk Hogan, John Cena, Brian Knobbs, Bret Hart, and other pro wrestling personalities can often be spotted sitting in the lower boxes. In 2009, Mr. Knobbs performed a few of his trademark moves on an utterly defenseless Raymond. The “incident,” as locals referred to the event during our visit a few years later, still evokes cringes at the Trop.

Sports in (and around) the City

George M. Steinbrenner Field

1 Steinbrenner Drive, Tampa

www.steinbrennerfield.com/about-george.html

Steinbrenner Field is the Grapefruit League home of the New York Yankees and the Florida State League home of the Tampa Yankees. It features outfield dimensions identical to Yankee Stadium, a facade that resembles Yankee Stadium’s, and a monument park similar to “The” Monument Park in the Bronx. Its grounds also include a large Yankees gift shop.

The park was built in 1996 at a cost of $30 million. Every game is a sellout during spring training but tickets are usually available to Tampa Yankees games and Monument Park is open to visitors any time during business hours. From St. Petersburg, take Interstate 275 to Exit 41B, then follow the signs on Dale Mabry North to the ballpark.

Josh:

Serves Raymond right for putting a smack-down on Wally, the Beanbag Buddy when the Sox were in town a few years ago.

Kevin:

You Red Sox fans never forget a slight, do you?

Josh:

Nothing real or perceived.

We Stayed All Sixteen

During our first trip to Tampa Bay we were treated to the longest game of our road trip, a 16-inning affair between the Rays and Red Sox. The game came early in our seminal baseball adventure at a time when we were still learning the dos and don’ts of staying with long-lost friends in faraway cities. We were staying with Josh’s old high school pal Aaron Fournier, who had gotten around to having kids a bit sooner than either of us had. Because we’d never had small babies at home, we couldn’t understand therefore, why Aaron was looking at his wristwatch all game long. We both always hoped games would progress as slowly as possible, but he was obviously chomping at the bit for the game to end so he could get home to help his wife with the nighttime routine.

And wouldn’t you know, the game was knotted 8-8 after nine innings.

Aaron also had to get up early for work at 5:00 a.m. the next morning, but as our trusty tour-guide he showed only slight signs of disappointment when the game went to extras or “freebies” as Josh likes to call them. These signs included a general scowl on Aaron’s face, a ringing of his hands and a sad whimper that he took to exuding every time he glanced at his watch. For our part, we sat blissfully waiting for extra innings to begin without a care in the world.

“Look at all the people heading for the gates,” Aaron said after the Rays stranded two runners in the bottom of the tenth. “They must have to get up early tomorrow too.”

A bit confused by our friend’s sour attitude we both opted to keep our mouths shut.

By the eleventh inning, Aaron had started mumbling things like, “I think you stop liking baseball around the tenth inning,” and “My wife’s not gonna let me go to another game for the rest of the season,” and “I’m really tired, can’t we just listen to the game on the car radio on the way home,” and “You haven’t visited me in ten years, Josh, and now you come down here to ruin my life?”

But although he kept threatening to drag us out of the Trop “early,” Aaron stuck it out with the true fans.

And what a thrilling game we saw. In the bottom of the thirteenth inning then-Red Sox left fielder Damian Jackson threw out a runner at the plate to preserve the tie. Then in the top of the fifteenth, Rays center fielder Rocco Baldelli returned the favor, gunning down a Red Sox runner at the plate. Talk about high drama and good times!

“If you ever ask to visit again, I’m gonna say ‘no,’” Aaron said to Josh in a voice that didn’t quite sound like he was joking.

The Red Sox finally took the lead at 12:30 a.m. in the top of the sixteenth inning when Kevin Millar blasted a solo homer to left.

“Good. Now can we leave?” Aaron pleaded. “The Rays aren’t gonna score in the bottom of the inning.”

“We don’t know that for certain,” Josh said.

“Yeah,” Kevin added. “They could tie it up and go another sixteen innings. You never know.”

Mercifully for Aaron, the Sox closed it out.

“Time spent in the ballpark,” Kevin said, looking at his wristwatch as we walked down the exit ramp, “Seven full hours: from 5:45 p.m. until 12:45 a.m.”

“Tough day at the office,” Josh quipped.

“I hate you both,” Aaron growled.

Josh patted him fondly on the back. Then Kevin did too.

“No, really. I hate you,” Aaron said.

The next morning, we were both fast asleep in the family room when Aaron left for work. And when his wife left for daycare and work too. It was a long time afterwards before Aaron would reply to Josh’s apologetic e-mails and even then he ended each electronic epistle, “P.S. I still hate baseball thanks to you!”

The moral of this story? We have no idea. But ever since the “Trop Incident,” we’ve been sure to tell our gracious hosts in cities far and wide that

The Ultimate Baseball Road Trip

boys are contractually obligated to stay until the final out of each game. That way our sleepy-eyed friends can blame the Lyons Press, and not us, when games continue into the wee hours.

MIAMI MARLINS,

MIAMI MARLINS,MARLINS BALLPARK

Finally, a Tank of Their Own

M

IAMI

, F

LORIDA

228 MILES TO HAVANA, CUBA

265 MILES TO ST. PETERSBURG

665 MILES TO ATLANTA

1050 MILES TO WASHINGTON

I

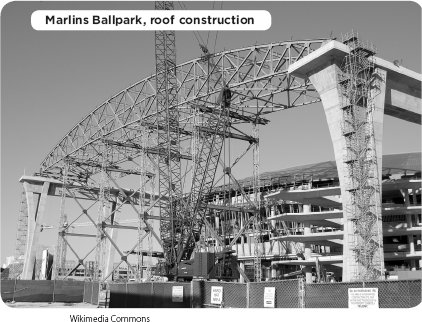

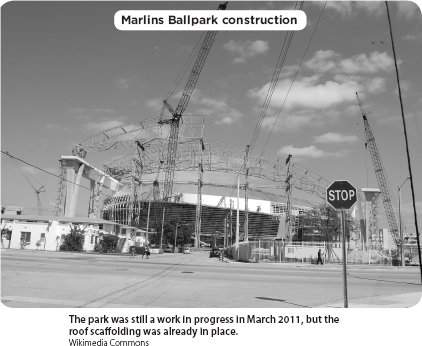

t was a long time coming, but fans in South Florida finally enjoy the wonders of baseball played in a state-of-the-art facility designed specifically to showcase all that is wonderful about the Grand Old Game. The Marlins entered the Show all the way back in 1993 but were forced, along with their fans, to endure nearly two decades of play at a retrofitted football stadium before Marlins Ballpark finally arrived in 2012. Located on a portion of the old Orange Bowl site in the Little Havana neighborhood of Miami, the Marlins’ shiny new park sits less than two miles west of downtown, boasting design elements and accoutrements that stamp it as distinctly Floridian.

First and foremost, the ballpark offers a comfortable, climate-controlled environment. As a summertime visit to Miami will surely convince you during your own baseball odyssey, air-conditioning is a must in these parts during the spring and summer months. The backyard swimming pool is more necessity than luxury for many Miami area locals as well, and the ballpark provides one of those beyond its outfield fences too. Sure, pools have appeared at ballparks before, most notably in similarly steamy cities like Phoenix, where the big league Diamondbacks play, and New Orleans, where the Marlins’ Triple-A affiliate, the Zephyrs, play, but Marlins Ballpark boasts some other novelties we’re pretty sure no one has ever seen at a ballpark before, like the live fish swimming between the dugouts. Yes, you read that right. The game’s first aquatic backstop is essentially a big long fish tank, or, actually

two

big long tanks. The Marlins wisely left the area directly behind the dish water-free, so the shimmering fishies and glare off the aquarium wouldn’t interfere with fielders’ views of batted balls. But on either side of the plate—where fans have grown accustomed to seeing classy red brick or pale limestone during the retro ballpark renaissance—the Marlins have installed massive tanks. The aquarium between the Marlins’ third base dugout and the batter’s circle measures thirty-four feet in length and holds six hundred gallons of saltwater, while the one between the plate and the visitors’ first base dugout stretches twenty-four feet and holds 450 gallons. The fish are clearly visible to fans sitting in the lower rows on the infield and to the players on the infield. There’s no need to worry about those fouls back to the screen that make the fans seated directly behind the plate instinctively duck. The fish are protected from harm by a type of polycarbonate known as “Lexan” (aka bulletproof glass), which measures 1.5 inches thick. Still not convinced? Thin sheets of Lexan less than one-eighth of an inch thick can stop a 9 mm bullet from passing through. Sounds good enough to us.

Of course, this fact wasn’t enough for the animal advocacy group PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), which sent a letter to the Marlins shortly after the team announced its plan to build the dual aquariums, and a public dialogue ensued concerning whether the bright lights and thundering noises of a baseball park would make Marlins Ballpark a suitable habitat for living creatures. In a letter to the Marlins, PETA executive vice president Tracy Reiman wrote, “Being exposed to the loud crowds, bright lights, and reverberations of a baseball stadium would be stressful and maddening for any large animals held captive in tanks that, to them, are like bathtubs.” PETA went on to request that the team “leave fish in the ocean where they belong” and suggested alternatives like an LED screen showing fish in their natural habitat, artsy blown glass fish replicas, and a tank full of swimming robotic fish. To this, Marlins president David Samson replied, “I guess that’s a philosophical issue, but there are beautiful aquariums all over the world and this will be one of them. I can assure you the fish will be treated as well, or better, than any fish can be.”

Kevin:

So, let me get this straight. The fish have front row seats to eighty-one games a year?

Josh:

Not just front row seats. Front row seats

behind the plate.

While it makes good sense for the “Fish” to celebrate the marine life and water-faring culture of their home market, Miami is also famous for its visually beautiful city skyline. The tall buildings of downtown are always striking, but are even more brilliant when they’re illuminated in shades of green, blue, pink and other colors on the occasion of festivals, conventions and other special events. Accordingly, the ballpark incorporates the view of the buildings into the game-day experience. Borrowing from the successes of retractable-roof stadiums in other cities that leave room for sweeping outfield views beyond their fences, the Marlins’ big-top leaves space between the seats and the roof high above left field for a window view of the Miami high-rises. Even when the roof is closed, fans enjoy this gorgeous visage through glass panels that reminded us of the sliding-glass giant windows above the fields at Minute Maid Park in Houston and Miller Park in Milwaukee.

However, there will be no confusing Marlins Ballpark with a park built in the retro-renaissance era. While the ballparks of the early 2000s almost uniformly presented visitors with arching old-time brick facades at street level, the designers of Miami’s later-generation park eschewed whatever muted temptation there may have been to build an old-timey brick bastion to the game’s glory years, and instead crafted a facility that better fit the sharp and architecturally modern image cut by the Miami cityscape. With its abundance of white stucco, its shiny silver metal and its wealth of clear glass, the Miami field was clearly built for those looking forward, not back into the game’s past. Along with Target Field in Minneapolis and Nationals Park in Washington, which similarly present more futuristic façades than the ones to which we fans came to know and love during the retro renaissance, Marlins Ballpark officially declares the end of the retro renaissance era of ballpark design, and announces a brand new era for the Grand Old Game, one that embraces the game’s entrance into the 21st Century, with respect paid to technology and innovation.

The Marlins treat fans to a couple of snazzy lighting tricks and special effects at their new yard too. Through some new age fiber optics tricks we two baseball writers are ill-equipped to fully explain, the four largest columns supporting the roof appear to rhythmically sway, move and practically disappear. The effect is subtle, but noticeable and strangely hypnotic. Josh likened it to watching the Sunday night baseball game on ESPN. You already know all the scores of the day, yet for some reason you spend more time staring at the scrolling names and numbers that are ever-present at the bottom of the screen than watching the lone game that’s still being played. Meanwhile, behind the center-field fence another bell and whistle of this park sits waiting to make its presence known. Equipped to rise on cue—a la the Home Run Apple at Citi Field in New York, or the lighthouse at Hadlock Field, in Portland, Maine—an ocean-themed display rises amidst a swirl of laser lights and jumping Marlins to celebrate home runs.

As the sixth and most recent retractable-roof stadium to arrive on the Major League Baseball scene, Marlins Ballpark really needs its lid. The 8,300-ton steel sunroof safeguards the game against both the famous Florida humidity and the frequent afternoon thunder showers that deterred many locals from attending games at the Marlins’ former home. This is Florida we’re talking about, where a higher percentage of the population exceeds sixty-five years of age than in any other state. And even if another segment of the population in Miami is a bit younger and hipper than there appears in the typical Sunshine State retirement community, it was unrealistic and unfair to expect folks to scurry down to the protection of a crowded concourse to wait out

the daily monsoon, and then to sit on a wet seat, breathing clammy air for nine innings. The Marlins realized this in time. But team management and the folks at MLB headquarters didn’t give up on the idea that Miami could and would one day lend robust support to the home team. With a thriving Cuban/Latin culture, a bustling finance and business district, and the usual Florida retirees and tourists, the Miami market has plenty of potential fans whose passion for the game will hopefully be reactivated now that the long-awaited ballpark has arrived.

Kevin:

It’s kind of pathetic that the locals didn’t do more to support a team that won two World Series in its first decade of existence.

Josh:

Imagine if your Mariners had turned that trick.

Kevin:

Folks would have been swinging from the Kingdome rafters.

The air-conditioning keeps the game-time temp pegged at a comfy 75 degrees. Based on Miami’s average daily temperature and rainfall averages, the Marlins know the roof will be closed and the AC will be pumping for approximately seventy of their eighty-one home dates each year. Anything beyond ten games beneath an open sky is a bonus. Now, to some people this might beg the question: Why spend the extra cash on a roof that’s going to be closed eighty-five percent of the time? Why not just build an old-fashioned dome? The answer lies in the sad reality that though the whiz kids in our nation’s bustling genetics labs have already mastered the fine arts of engineering seedless grapes and apple trees that grow McIntosh fruit on one branch, Cortland on another, and Delicious on another, they still haven’t figured out how to grow natural grass indoors. And besides, even ten or eleven outdoor games a season are worth the extra effort of adding a roof that can be peeled back. Dome baseball is an abomination.

Kevin:

Domed baseball is kind of like microwave pizza.

Josh:

Or instant coffee.

Kevin:

It will do in a pinch, but the real thing’s always better.

To appreciate just how long the Marlins waited for a new park, consider this tale of two baseball cities: Miami and Denver. Both joined the National League as expansion franchises in 1993. Each had rightly been identified by the game’s power brokers as possessing a growing population and a reputation as a hip and trendy city. Both could lay claim to having a track record of supporting highly successful teams at the top level of another professional sport, namely football, where the NFL’s Miami Dolphins and Denver Broncos were bona fide pigskin royalty. Both NL newbies played their inaugural seasons at longtime NFL stadiums converted for baseball, as the Marlins trotted out on the lawn at Joe Robbie Stadium and the Rockies basked in the thin mountain air of Mile High Stadium. Both arrangements were thought to be temporary, as the expectation throughout the game was that the two newcomers would settle into their own baseball yards before very long.

For the Rockies, this was true. Even as they set a home attendance record that still stands in 1993, when they drew 4,483,350 spectators through the Mile High gates, the Rockies were working to ensure the timely completion of beautiful Coors Field, which would open in 1995. For the Marlins … well, let’s just say things didn’t move quite so rapidly from a stadium development standpoint. The Fish surpassed the three million mark in home attendance in their first season and won two World Series in their first eleven years of existence, but after the excitement surrounding the team’s debut wore off, it seemed they were always swimming upstream when it came to drawing fans to regular season games. They only reached the two million mark in home attendance one other time after their inaugural campaign.

Even in their second World Championship season of 2003, when they beat the New York Yankees in the World Series, they drew just 1.3 million fans, or sixteen thousand per game, and ranked twenty-eighth out of the thirty teams in Major League Baseball in fan support.