Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (63 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Josh:

You’re praying? Is this a church or a baseball park?

Kevin:

Both.

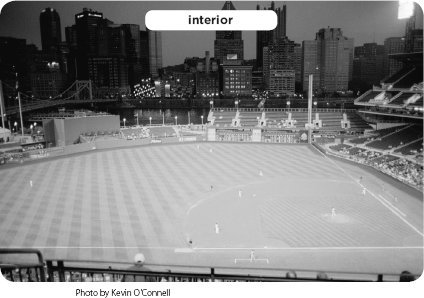

Beautiful as PNC is, we would be remiss not to mention that the experience of visiting this gem of a park has indeed been more than a bit hampered by the Pirates’ lack of success on its field. After going 96-66 in 1992 and playing the Braves for the National League championship, the Pirates went the rest of the 1990s and the entire first decade of the 2000s without posting a winning record. This gave them the dubious distinction of having the most consecutive losing seasons of any pro sports team in North America.

There are those who would claim that Pittsburgh is, and always has been, a football town, and that baseball will always play second fiddle behind the Steelers, or third fiddle behind Pitt Panther football, or even fourth fiddle behind any random high school football team that might happen to play nearby. And a cursory view of the sporting section of the

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

might support this theory. But it is a mistaken notion—and one that we ourselves made in the first edition of this book. The fact is, Pittsburgh is a town that loves winners, and especially those that have “Pittsburgh” emblazoned on their chests and carry the trademark black and gold. It’s a town that loves sports so much that it will support nearly any local team that does not tarnish its reputation as “City of Champions.”

Sadly, the current Pirates owners have been accused by their own fans, perhaps rightfully so, of not really truly trying to compete. Pirates’ fans have accused the owners of selling off every decent player that comes up, right before he is due to earn a competitive paycheck. They have accused the owners of putting teams on the field that simply are not equipped to be competitive, and they support their argument by pointing to the Pirates’ dismally low payroll. They have accused the owners of milking the corporate welfare system in place—MLB’s revenue sharing (known as the Luxury Tax)—to deliver profits to their investors, without putting proper monies back into the franchise to be competitive via payroll. And perhaps worst of all, they have accused owners of simply not caring, of taking a once glorious franchise and shamelessly flushing its reputation down the drain and into the Allegheny River like a goldfish grown too big for its bowl.

The current ownership group, which is led by Bob Nutting, claims small market inequities dictate the necessity of the Pirates’ personnel moves. But this doesn’t fly with the general Pittsburgh sports fan—especially not when they continue to win Stanley Cups and Lombardi trophies just down the street. Nutting and the rest of the Pirates owners have made it difficult to refute any of the fans’ complaints. And their public relations effort is often so horrific that they seem to vacillate between not understanding what they are doing and not caring. Owing to this ownership continuum that has gone from mediocrity to ineptitude, many potential fans have simply written off the Pirates as losers. Meanwhile, a generation of potential new fans has been born, grown up, and graduated from high school having never known the Pirates to have a winning season.

In this dysfunctional world of Pirates family dynamics, the fans have even turned against one another. The boycotters claim the only way to send a message to the owners is to steer clear of the ballpark. The loyalists, who continue to go to the games, claim a variety of reasons for still going, but mostly because they simply love the game too much and can’t stay away. To this, boycotters say loyalists are part of the problem. The loyalists claim that boycotters are fair-weather fans, and that they themselves are the true fans,

having stuck by the team through high tide and low. Sadly, both sides simply want a team they can be proud of, but without management’s cooperation, they’re powerless to produce one. It’s criminal that the Pirates have been mismanaged into such a state of ineptitude and fan disaffection, given the great success the franchise has enjoyed over its long history. As bad as the Pirates have been recently, only six franchises can claim more World Series victories than the Buccos, and only four can claim more inductees to baseball’s Hall of Fame. Think of Clemente, Stargell, Honus Wagner. Quite simply, those are some of the best players to ever play this game and they were Pirates.

Josh:

How many World Series rings does Seattle have again?

Kevin:

Hey bud, your Sox haven’t won since 19—, um. Oh, never mind!

Most Pittsburghers point to the 1992 NLCS loss to the Atlanta Braves in Game 7 as the exact point in time when the Good Ship Pirate began to submerge. Starter Doug Drabek pitched eight masterful innings only to see a catastrophic turn of events. When submarine-armed closer Stan Belinda took the mound in the bottom of the ninth, the Pirates still led 2-0. With the bases loaded and two outs, Francisco Cabrera lined a single to left field to bring in the go-ahead run, Sid Bream, a former Pirate who couldn’t have lumbered in from third more slowly if he’d been named Forrest Gump. Some Pirates fans took heart. With a roster that included Barry Bonds, Bobby Bonilla, Jay Bell, Denny Neagle, Tim Wakefield, and Drabek, fans felt the next championship would come their way soon. But it didn’t. One by one, the Pirates’ top players departed via free agency, and the team sank in the standings year after year.

Josh:

I remember watching that game my freshman year of college. Since then I’ve completed college and grad school, worked for fifteen years, gotten married, bought a house, had a child, written some books … and the Pirates still haven’t had so much as a winning season.

Kevin:

When you put it that way it seems even worse.

Despite their recent hard times, the franchise has enjoyed many shining moments:

- The Pirates fielded what is generally regarded as the Major League’s first all-minority lineup on September 1, 1971.

- The Pirates won a World Series the year after moving into Forbes Field by beating Detroit in 1909, and a little more than a year after moving into Three Rivers, they won their fourth October Classic, beating Baltimore in 1971. Clemente batted .414 in the Series, and hit a Game 7 homer while Steve Blass tossed a four-hitter. The Series also featured the first night game in World Series play.

- When the Pirates won the World Series again in 1979, they did so with the catchy disco number “We Are Family” as their anthem and with the big bats of Dave Parker and Stargell leading the way.

- In 1994 Three Rivers played host to its second All-Star Game (the first was in 1974). It was the largest crowd to see the Midsummer Classic, as 59,568 fans witnessed an 8–7 NL victory that took ten innings to complete.

As mentioned, Pittsburgh’s hardball history ranks among the richest in the Majors. Back in 1887, the Pittsburgh Alleghenies played at Recreation Park, a facility that seated fewer people than Wheeler Field, in Centralia, Washington, where Kevin played his Babe Ruth ball. Not really, but it was small. It was there that the team garnered the name “Pirates,” when a Philadelphia newspaper claimed the team had hijacked slugging second baseman Louis Bierbauer away from the Athletics. There was no wrongdoing, but the name stuck.

In October 1903 the Pirates played the Boston Pilgrims in the first World Series, but lost five games to three in the best-of-nine set. The Pirates did manage to win the first-ever World Series game, which was played in Boston, before returning to Pittsburgh—spelled “Pittsburg” at the time—to host the early Red Sox at Exposition Park. The small wooden facility sat on the north shore of the Allegheny, spitting distance from where PNC Park would open a century later. A historical marker of the first Series has been erected on the site, just a short walk from PNC.

Even before that, way back in 1882, the old American Association Alleghenies played baseball in the open fields of Exposition Park. But the park flooded often and the league folded. There were no outfield fences at “The Ex” and crowds respectfully lined up behind rope boundaries. Clearly this was another era for baseball fans. It may not have had outfield fences, but an interesting innovation debuted there when the Pirates used a tarp to cover the infield during a rainstorm. Other cities quickly followed suit.

In 1909 Pittsburgh opened gorgeous Forbes Field, named after British General John Forbes, who in 1758 captured Fort Duquesne from the French and renamed it Fort Pitt. It was the first ballpark in the country built completely of steel and poured concrete. A beautiful structure with a stone facade and arched windows along its exterior,

its most important feature was its seats close to the action. Forbes was a park of the grand design, a rival to Wrigley and Fenway. The outfield was enormous and the park itself had a clunky shape. The flagpole in left field was actually in play. To commemorate their love for the old park, the Pirates designed PNC to imitate Forbes’ blue steel, tall “toothbrush style” light standards, and blue seats.

In the first season at Forbes, Wagner led the Pirates to their first World Series title, downing Ty Cobb and the Tigers in a Series that went seven games. Wagner—whose tobacco card fetched a record $2.35 million in a 2007 auction—had help in the Series from rookie hurler Babe Adams, who won three games, including a Game 7 shutout in Detroit.

There were many firsts and lasts at Forbes Field. The last tripleheader in MLB history, for example, was played there on October 2, 1920, between the Pirates and Reds. The first radio broadcast of a baseball game emanated from Forbes in 1921. The first elevator in the Majors was built to shuttle fans up to the “crow’s nest” bleacher seats. And Forbes was the first stadium to install foam crash pads on its outfield walls.

In 1925 the Pirates claimed another championship, sealing the deal at home in storybook fashion. In the eighth inning of Game 7 with two outs and the bases loaded and fire-baller Walter Johnson on the mound for the Senators, Kiki Cuyler laced a three-run double to propel the Pirates to a 9-7 win.

Another amazing Forbes moment occurred on May 25, 1935, when Babe Ruth—playing for the Boston Braves—hit the last three home runs of his career. Ruth’s final blast, number 714, cleared the right-field roof to mark the first time a shot had ever left the Forbes yard.

In 1955 Forbes witnessed the debut of a twenty-year-old rookie from Puerto Rico by the name of Roberto Clemente. No. 21 would prove to be the last right fielder to play at Forbes for the Bucs, patrolling the post until the ballpark closed in 1970.

In 1960 Bill Mazeroski hit a shot in the bottom of the ninth to break a 9-9 deadlock and carry the home team past the Yankees in Game 7 of the 1960 World Series. The legendary swat, which cleared the left-field fence, gave the Bucs their third World Series title and first in thirty-five years.

Even if the Pirates’ glory years seem a distant memory, PNC provides Pittsburghers a premium environment in which to see a ballgame. Just as steel is an alloy that derives its strength by the fusion of two or more other metals, PNC Park has taken the best of Forbes, Three Rivers, Exposition Park—as well as Wrigley, Fenway and other more contemporary ballparks—and fused them into a single structure. The city and the team should be proud of PNC.

Trivia Timeout

Schooner:

Which Pirates pitcher authored the first no-hitter ever thrown in Pittsburgh? Hint: He did it in 1976.

Frigate:

Of the four players honored with statues outside PNC, which has a museum in his honor?

Man-O-War:

Which Pirates player passed away the day PNC Park opened?

Look for the answers in the text.

All that remains for the plan to come together is for the owners of the Pirates to field a championship team—or at least one with a reasonable shot at achieving a .500 record. When they do, the fans will stop their bickering

and return to arguably the best new ballpark in the country. Then we’ll see if Pittsburgh is really a football town or not.

A partial answer came during June 2011 when a red hot Red Sox team came to town for interleague play. Odd as it was, the Pirates had been flirting with .500 well into June, a feat that had been so long in coming that nary a Bucco fan could remember the last time it occurred. A PNC Park attendance record was broken for the Saturday night game, June 25th, when 39,441 fans turned out, then broken again the next day when 39,511 fans attended. The Pirates took the series 2-1 from that much-ballyhooed Sox team, and the three-game series broke the PNC Park series attendance record as well, drawing 118,324 fans.

Josh:

We travel well, don’t we?

Kevin:

You might as well be wearing red pin stripes.

PNC is the most intimate new park when it comes to seating, as is evident by the fact that the press box is up above all of the fans, even those who pay the least money. Only Nationals Park in Washington has a more altitudinous press box than the one in Pittsburgh. Luxury boxes hang from the upper deck rather than garnering their own level. There is very little foul territory, getting fans even closer to the action. And the seats all angle toward the infield, with aisles that are lowered to prevent views from being blocked. The only problem with this feature is if you’ve gone to the game to gab with your buddies, the angled seats will have you talking over your shoulder. But who cares? You can yuck it up afterward over a few pints.