Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (94 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

After the game on Sundays the Twins let kids fourteen and under onto the field to run around the bases. When the game ends, just head to the North Ramp area on the Main Concourse, near Section 130, and an attendant will direct your youngster onto the field.

Kevin:

Now, this is the important part, so listen up.

Josh:

If you have a very young child, the Twins allow an adult onto the field to accompany him or her around the bases.

Kevin:

I never knew having a kid would be so rewarding!

We Visited the

Field of Dreams

Movie Site

www.fieldofdreamsmoviesite.com/distance.html

On the way from Milwaukee to Minneapolis we passed up a scintillating opportunity to visit the Spam Museum in

Austin, Minnesota, and opted instead to hit Dyersville, Iowa, where the field that was created for the 1989 film

Field of Dreams

can still be found. It is about 185 miles from Milwaukee, 210 from Chicago and 290 from Minneapolis.

Sports in the City

The Mall of America

Killebrew Drive, Bloomington

No visit to the Twin Cities would be complete without a trip to the Mall of America, the world’s largest covered shopping center, in nearby Bloomington.

Yeah, we know, malls are to shopping what domes were to baseball: covered, sterile, and all similar. But this jumbo emporium has a legit ballpark landmark beneath its roof. Head for the Mall’s seven-acre indoor amusement park and after a bit of a scavenger hunt you’ll find a unique tribute to Metropolitan Stadium, which stood on this site from 1956 until 1984. The ballpark attracted twenty-two million people in twenty-one Major League seasons. The mall attracts nearly twice that many in a typical year.

Inside the amusement park, look for the red stadium chair mounted above the water ride some 520 feet from where the Met’s home plate resided. The seat commemorates the landing spot of Killebrew’s longest homer in team history, which he smacked against the California Angels’ Lew Burdette in 1967.

Before departing in search of an Orange Julius or plate of Bubba Gump’s shrimp, pace off 520 feet and find the marker commemorating home plate.

The field exists on two abutting plots that are owned by two different families. Parking is free, fans are encouraged to bring their gloves and have a catch, and there are two small souvenir stands on site. In a typical summer, baseball pilgrims hailing from all fifty states and from several foreign countries stop by for a catch and to sit in the same bleachers where Ray and Annie sat.

Sports in the City

Midway Stadium, Home of the St. Paul Saints

1771 Energy Park Drive, St. Paul

Across the Mississippi in St. Paul, Kevin wanted to see the birthplace of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Josh, meanwhile, wanted to visit Cretin-Derham Hall, where Joe Mauer played his high school ball, and Mauer Chevrolet in Inver Grove Heights, which is owned by Joe’s brother Billy, who played minor league ball in the Twins system before an injury forced him to retire.

We compromised and set a course for one of the most successful minor league operations in the country. We visited Midway Stadium, home of the St. Paul Saints.

The American Association Saints have been filling 6,329-seat Midway Stadium since the early 1990s. The team is owned by Mike Veeck—the son of baseball promotions guru Bill Veeck—and comedian Bill Murray, who sometimes coaches third base. Management, players, and fans all embrace a “fun is good” motto. A pot-bellied pig waddles around the field delivering fresh balls to the home plate ump, fans get haircuts and massages while watching the game, and the Saints stage one goofy promotional night after another. In 2011, after the Metrodome roof collapsed during the previous football season, prompting the NFL’s Vikings to move a home game to Detroit, the Saints staged “Deflation Night,” during which a park full of fans sat on Whoopee Cushions. Another recent draw was “Life Before Toilet Paper Night,” when the Saints paid tribute to the history of butt-cleansing toiletries while collecting rolls of TP at the gates for the benefit of a local food pantry. Our all-time favorite Saints theme night remains, however, Bud Selig “tie” night, which occurred shortly after the ill-fated 2002 game that ended in a deadlock. On that night, the Saints gave out neckties bearing Selig’s face.

The Ameskamp family owns the left and center-field portions of the diamond, while the infield and right-field portion of the diamond belonged to the Lansing family until October

2011. The field and house appear exactly as they did in the film, except for the power lines that bisect the field, running from behind third base out through centerfield, which were apparently there all along but deleted from scenes by the technical whiz kids working the mixer board at Universal Studios.

Upon our visits to the field, Don Lansing, the elderly gentleman who lived in the farmhouse from his childhood until his senior years, was happy to recount for us his initial reaction on being approached by a Universal Studios executive proposing to turn under his soybean and tobacco plants, build a baseball field, and plant cornstalks across the “outfield” portion of Don’s land. “You want to build a ball field here?” Don recalled asking incredulously. If that sounds like the response Ray Kinsella got from his friends and family members in the movie, you’re right.

In any case, Don stopped asking questions when Universal cut him a check, and then he watched in amazement as his land was leveled, sod was laid, and light towers were erected, all in a span of a few days. After the movie was shot—including the dramatic final scene that included some 1,500 local residents and their cars making their way up Don’s driveway—Don decided to maintain the field for local residents and visitors to use. Never did he imagine it would become a site of national tourist interest.

When we visited the Field of Dreams for a second time in 2011, the larger portion of the field was for sale. In fact, the whole 193-acre Lansing plot was, along with the farmhouse and several barns and garages. Later, in October of 2011, the Lansings found a buyer. The plot sold to Mike and Denise Stillman of Go the Distance Baseball LLC. Upon closing the multi-million-dollar real estate transaction, the Chicago-based couple announced their intention of turning the Field of Dreams into a massive youth baseball complex that should be completed by 2014.

HOUSTON ASTROS,

HOUSTON ASTROS,MINUTE MAID PARK

Juice Box Baseball in Space City

H

OUSTON

, T

EXAS

255 MILES TO ARLINGTON

750 MILES TO KANSAS CITY

800 MILES TO ATLANTA

870 MILES TO ST. LOUIS

W

hen Houston unveiled baseball’s first domed stadium in 1965, many billed the Astrodome the Eighth Wonder of the World. And when Minute Maid Park replaced the aging dome in 2000, many Houstonians dubbed the new retractable-roof facility the Ninth Wonder of the World. Certainly, that is overstating the significance of Minute Maid Park on the Major League Baseball landscape. Minute Maid was not the first ballpark to be built with a retractable roof, nor does it make use of technology that is noticeably superior to the retractable-lid parks in Phoenix, Milwaukee, and Seattle. Nonetheless, it is understandable that folks in the humidity capital of the world are proud of their downtown ballpark. While we could write something along the lines of “For a retractable-roof stadium it acquits itself rather nicely,” we will go a step further and say, “Without qualification, Minute Maid is a gem.”

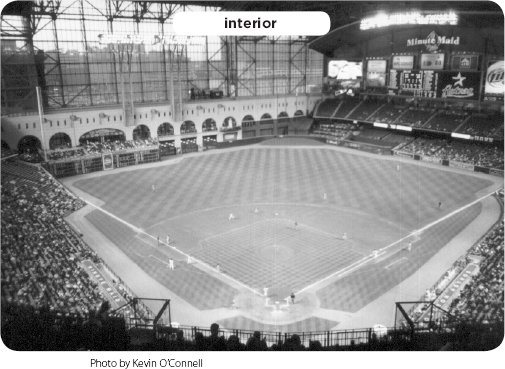

Smaller than its retractable sister stadiums, Minute Maid provides a great environment for a game, whether the roof is closed or opened. Old-time brick arches rise up beyond the outfield fence, a massive window above left field allows an abundance of sunshine to soak the field as well as a glimpse of the stars at night, and quirky field dimensions keep outfielders and fans on their toes. Best still, the playing surface is natural grass. Even in the land where Astroturf was invented, it has been forsaken. Are you reading this Toronto?

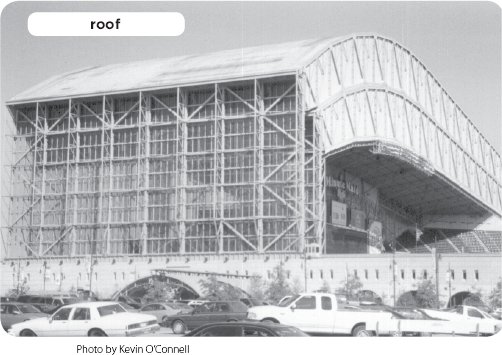

It will come as no surprise to those who have visited a number of the current MLB parks that Minute Maid was designed by the architectural firm once known as HOK that has since changed its name to Populous. The park oozes retro charm. Concrete and steel are featured prominently in the interior and exterior design along with brick, brick and more brick—behind the plate and even on the upper levels’ interior concourses where ordinarily mere concrete would appear. The facade is made of limestone, while the top two stories are nicely done in brick with arched windows. The facade juts out every one hundred feet or so with a building-type edifice, giving the ballpark more the look of an office building than a typical ballpark. The roof is a color significantly paler than traditional ballpark green, channeling a corroded copper look.

The main entrance—located at the corner of Texas Avenue and Crawford Street—is one of the most distinctive in all of baseball. This gateway to cooler air and good times to follow makes use of Houston’s pre-existing Union Station, which the new structure was built around. The classy marble pillars and regal arches inside the main entrance were originally envisioned by Whitney Warren, the same architect who designed Grand Central Station in New York City. Built in

1911, Union Station was once the hub of Houston’s bustling railroad industry. Today, along with providing an entrance to the ballpark, it houses an Astros souvenir store, a café, and the Astros’ executive offices.

Complementing the old-time motif anchored by Union Station is a tall tower that rises up from the ballpark’s edifice. From atop this perch emanates the sound of chiming bells (not real bells, but a good-sounding imitation) playing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” as if calling baseball worshippers to mass. Large windows beside the Union Station entrance to the ballpark furnish fans with a street-level peek at the sunken playing field inside. From inside the park, meanwhile, fans can look through the arches that rise behind the left-field seats and see clear through the station to the world outside the park. High above it all, for the viewing delight of those inside and outside the park, a replica nineteenth century locomotive chugs along an eight-hundred-foot track that traces the arches running from center field to left field. The train weighs more than fifty thousand pounds and comes complete with a linked coal-tender’s car that is loaded with faux oranges that are in fact big enough to be pumpkins. While we usually don’t go for such bells and whistles, we are happy to make an exception in this case seeing as the ballpark is built at and makes such classy use of an old train depot.

In another thoughtful nod to the local ethos, an oversized vintage gas pump resides on the left-field concourse, between two of the arches, perpetually updating the number of home runs the Astros have hit at Minute Maid since its opening. Oil is king in Texas and will remain so no matter how many windmills T. Boone Pickens manages to sell.

Kevin:

Hey look, there’s a Citgo sign high above left field too, just like at Fenway.

Josh:

Um, the one at Fenway isn’t mounted on a big retractable window.

Another neat feature at Minute Maid is its in-play embankment in center field, which recalls the similar outfield knolls that once appeared at Crosley Field in Cincinnati and Fenway Park in Boston just to name a couple. Houston’s embankment, named Tal’s Hill after longtime team president Tal Smith, rises at a twenty-degree angle, measures ninety feet at its widest point, and spans one hundred feet of outfield fence. You don’t realize just how big it is when watching a game on TV. While we think this is an interesting and unique touch, we dread the day when a hard-charging visitor like Carlos Gonzalez or Shane Victorino tears an ACL stumbling after a long fly ball, or worse, runs into the flagpole that is in-play atop the hill. We’re thinking Tal’s Hill wouldn’t be very popular after that. And if an Astros player got hurt, Tal Smith might not be either. But maybe we’re just worry-warts. The flagpole is some 436 feet away after all. And the hill rises gradually.

The roof, which is similar in its three-panel design to the one in Seattle, allows for the largest open area of any of the sliding-roof parks. It weighs eighteen million pounds and covers more than six acres. Unlike the umbrella in Seattle, however, the Minute Maid roof seals up airtight to keep the heat and humidity out and the air-conditioned air in. The aforementioned window in left—which is actually a fifty-thousand-square-foot sliding wall of glass—offers fans a view of downtown Houston when the roof is closed. When the roof is open, the window is retracted into the bowels of center field. This design element, combined with the ballpark’s relatively cozy confines compared to the other roofed yards, makes Minute Maid a vast improvement over Chase Field and Miller Park, which also seal up airtight. While Safeco in Seattle may be larger than Minute Maid, it maintains an outside feel even when the roof is closed. And that’s worth major points in our book.

Besides the roof and sliding glass door, the grass on the field is also especially designed to mitigate Houston’s sweltering summer days. Known as Platinum TE Paspalum, the grass

was developed to thrive near salt water and in high temps, making it a popular choice for golf courses overlooking the ocean waves. All of these weather-related modifications are necessities in Houston, where the average high temps remain above 90 degrees Fahrenheit throughout June, July, and August, before it cools all the way down to 88 in September. But to co-opt an old and annoying cliché, it’s not the heat—it’s the humidity. With summer dew points perpetually hovering in the “you’ll sweat your butt off zone,” Houston would be a sticky place to watch, much less play, outdoor baseball.

After several years of mounting dissatisfaction with the Astrodome on the part of fans, players, and Astros management, rumors began swirling in 1995 that the team was pondering a move to northern Virginia. Fearful of losing the home team, the City of Houston got to work exploring new ballpark possibilities, and in November 1996 voters approved a referendum to construct a new downtown ballpark. Financing was provided through a combined effort by the private and public sectors with a partnership of fourteen Houston-area businesses contributing $35 million in the form of an interest-free loan to the city. The entire project cost $250 million, comparatively little considering the price tags of the retractables in Seattle ($500 million), Phoenix ($350 million), and Miami ($515 million). We’re not sure if the Astros cut corners, used non-union labor, or propped up their roof with discount steel from China. However they did it, we say, “Well done!” The savings are reflected in the ballpark’s reasonable ticket prices. And if a few unattractive HVAC ducts—exposed on the ceiling of the first-level concourse—are the price to pay for cheap tickets, we say that’s a trade we’ll make any day, especially considering that those ducts are working hard to keep the joint cool.

Construction began on October 30, 1997, and was completed in time for Opening Day 2000. After a preseason tilt between the Astros and Yankees, the ballpark made its regular season debut before a full house on April 7, 2000, with the Phillies downing the home team 4-1.

In its first two years of existence the new ballpark sported three different names. It was originally called Enron Field, thanks to a thirty-year, $100 million naming-rights deal with Enron. But when the “Infamous E” filed for bankruptcy in 2002 amidst a swirl of scandal, the Astros did everything they could to disassociate themselves from the notorious energy company. The team paid $2.1 million to buy back rights to its own ballpark’s name and temporarily renamed the park Astros Field. Just a few months later, the Astros announced a deal with local orange juice company Minute Maid, and renamed the yard Minute Maid Park. In effect the Astros swapped one juice company on their marquee for another. And you probably thought only the players and balls were juiced back in the early 2000s! Kidding aside, Enron’s collapse actually benefited the Astros. The new deal with Minute Maid was more lucrative, paying $170 million over twenty-eight years, or $6.07 million per season. Of course, these days a team’s lucky if it can sign a fifth starter for $6 million a year, but hey, every little bit helps. The ballpark’s unofficial nickname, “The Juice Box,” is also kind of cool.

While the Astros and their fans are ecstatic to have a new ballpark to call their home, they are still proud of their former digs—and perhaps that is why the Astrodome still stands beside the Houston Texans’ Reliant Stadium. At the time of this printing, there were three plans being considered for the venerable granddaddy of the domes. The first would demolish the dome and replace it with a public green space. The second would preserve its outer shell, while demolishing the stands and concourses to create an expansive ground-level capable of hosting conventions, weddings and other events. The third would make the changes described in option two, but rather than making the ground level into a function space would make it into a science and technology learning center, complete with a planetarium.

Kevin:

Boy, I sure hope they don’t rush into anything they’ll later regret.

Josh:

It’s been sitting empty for more than a decade.

Kevin:

That was a joke.

While allowing that its era passed it by, we should not forget the Astrodome and the defining moment its opening represented in the life of our National Game and in the life of American sport. While looking back on it we now see the dawning of a regrettable era of artificial playing fields and sterile, oversized facilities. But in its day the dome was a marvel, an example of a team reaching for the stars and forever upping the ante in the field of stadium architecture. The Astrodome originally symbolized American decadence. From the cushioned seats and comfortable air-conditioned environment, to the shoeshine stands behind home plate, to the ballpark lighting system that required more electricity than a city of nine thousand homes, the Astrodome represented American opulence. Elvis played the Astrodome. And the Rolling Stones. And Billy Graham led huge Bible-thumping crusades there. For a number of years, the Astrodome was the world’s ultimate entertainment venue. It stood for something bigger than just Houston. It was a monument to American industrialism, workmanship, and vision. And most importantly to local ball fans, the Astrodome brought Major League hardball

to Texas. When Houston was awarded an expansion team in 1960, the dome was already in the works. Had Houston not had specific plans for a weatherproof ballpark, it would have never been granted a franchise. The Colt .45s—as the Astros were originally called—joined the National League with the Mets in 1962. While the Mets would go on to capture a World Series title before the end of the decade, Houston continues to seek its first World Series championship. The Astros are currently the longest existent Major League team to have never won one. In fact, they’d never even appeared in the World Series until 2005 when they were swept by the White Sox.