Ultramarathon Man (17 page)

Authors: DEAN KARNAZES

Badwater.

The vomiting started at mile 30. Severe dehydration and cramping followed. I was less than a quarter of the way into it, and already things were going haywire.

My friend Tom Servais hosing me down at Badwater

“How about trying some food?” my dad asked from the Mazda window.

“Sure, I'll try anything.”

He lowered the window and handed me a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. I ran with the sandwich for perhaps a hundred yards, trying to stave off the nausea enough to take a bite. When I finally chomped into it, I found that the bread was toasted.

That's strange,

I thought to myself,

Why would we bring a toaster to Death Valley?

Then it occurred to me: I was

running

in a toaster.

That's strange,

I thought to myself,

Why would we bring a toaster to Death Valley?

Then it occurred to me: I was

running

in a toaster.

It was 1:00 A.M. as we made our way into Stovepipe Wells, 42 miles from the starting point of this godforsaken race. The road was dark and silent as I ran, except for the whistle of the wind howling across the barren expanse of desert and the periodic tumbleweed bouncing along the way. It was pitch-black when we arrivedâthe middle of the nightâand the temperature was 112 degrees. Birds had fallen from the sky earlier in the day.

Stovepipe Wells has a single hotel, with a small pool. I ran straight to it and jumped in. Unfortunately, the water was as warm as a Jacuzzi. As I climbed out, another runner ambled up to the pool. He was dry-heaving continually, and, under the pale-yellow glow of the naked bulb illuminating the area, I could see him lurching uncontrollably. He stepped feetfirst into the pool without removing any of his running gear, shoes included. He was still dry-heaving when he clambered back out, dripping wet. He passed his crew in a daze.

“Did it help?” one of them asked.

He shook his head and staggered past them, straight into the hotel. That was the last we saw of him. Game over.

Exiting Stovepipe Wells, I was hallucinating vividly as I trotted along. The farther I progressed, the more delirious I became. At one point an old miner appeared in the road ahead of me, gold-dust pan in hand.

“Water,”

he croaked. Feeling sorry for him, I filled his pan from my bottle. It was only when the water splashed and steamed on the road that I realized he was a hallucination. Or a ghost.

“Water,”

he croaked. Feeling sorry for him, I filled his pan from my bottle. It was only when the water splashed and steamed on the road that I realized he was a hallucination. Or a ghost.

Then came hallucinations of rattlesnakes on the road. “Look out!” my dad and uncle screamed, flashing the headlights and honking. The snakes were real.

Besides the rattlesnakes, there were scorpions and big tarantulas to watch out for on the dark road. My vision wasn't very focused, and my mind was in a haze. I plodded along recklessly, unable to remain mentally attentive. My guard was down at a time I needed to tread cautiously.

At four in the morning, along with the vomiting came severe diarrhea. My stride was so shaky that I could barely make it to the shoulder of the road to yank down my shorts and expel wretchedly from both ends simultaneously. The next remote outpost, Panamint Springs, was at mile 72. I needed to get there soon, if only for a roll of toilet paper. We had run out long ago.

My dad and uncle were with me straight through the night. They would pull the car some two miles up the roadâlooking for crittersâand then would wait for me to saunter by, always ready to help. Although I'd stopped eating and drinking long ago, for fear of ejecting the products, they kept up the support all the way through.

The toughest footrace on earth was kicking my ass. The official finish at road-end on the side of Mount Whitney was still 63 miles away, and I had no intentions of stopping there. With my newfound spirited determination, I wanted to make an extreme endurance event even more extreme by blasting through the finish line and running eleven additional miles up the trail to the summit.

Call me a masochist. Plenty of people were starting to.

I was thinking that myself as I staggered into Panamint Springs, hunched over like an ape. My head was spinning and I saw stars, though it was now daylight. Someone decided I needed fruit and stuffed a piece of warm, limp cantaloupe in my mouth. I threw it up immediately.

“Is he all right?” I heard a man ask my crew. It was Ben Jones, M.D., the local doctor, surgeon, obstetrician, pediatrician, psychiatrist (lord knows they need one out here), and mayor of Badwater.

“We're not sure,” my dad answered.

“Would he like to use my ice bath?”

Behind his car, Dr. Jones was towing a coffin on wheels filled with ice water.

I shook my head. There was no way in hell I was crawling into a coffin, even for an icy cold bath. The prospect of ending up in one for good seemed all too real.

I could dimly make out the doctor consulting with my dad and uncle. They sounded like a bad transistor radio, complete with static and irregular volume. I looked up; the sun appeared to be pouring down in a molten red mist that swirled around the distant dunes and then weirdly evaporated back up into the sky. I took a step forward, veered sideways, took another wobbly half-step, and collapsed in a heap on the burning ground. . . .

Â

Â

Â

When I awoke,

the hotel sheets had been removed from the bed, and I was lying naked in a puddle of sweat.

the hotel sheets had been removed from the bed, and I was lying naked in a puddle of sweat.

“Where am I?” I mumbled. “Dad? Uncle George?”

“Would you like a towel?” my wife asked softly.

I squinted up at her face. “What are you doing here? Where are we?”

“The race is over, honey. You're at a hotel in Lone Pine.”

“But I didn't finish, did I? How did I get here?”

“You were driven here. You passed out.”

“No!” I croaked. “Why did they take me away?”

“Let's see: you were severely dehydrated, vomiting, slurring your words, and on the verge of heatstroke.”

“So?”

“So when you passed out, they thought enough was enough.”

“But I was only halfway done.”

“It sounds like you were all the way done.”

“I can't believe they carted me away like that.”

“Would you like me to take you back out there?” she volunteered.

The idea of heading back into that inferno triggered an impulse of nausea. I sat up, wincing. I could see circular pus stains discoloring the sheets where my blisters had oozed a yellowy discharge from the abscesses covering both heels.

“I failed. I'm a failure.”

“You did not fail, and you are certainly not a failure,” Julie said firmly. “You ran seventy-two miles without being able to keep anything in your system. How much farther are you willing to go?”

To Julie, the bad luck encountered out in the desert was just something to be taken in stride, a bump in the road, not the end of the road. There would be other races to run.

Julie was rational. I wasn't. To me, it was complete, incomprehensible devastation not to finish Badwater. It didn't occur to me that this distorted overreaction possibly came from the same internal force that drove me to run great distances and allowed me to endure unfathomable amounts of pain. Most people would let it go at a point. Win some, lose some. But to me, failure was terminal. In my way of looking at things, it was more honorable to die trying than to give up. Thank God I'd passed out back there; who knows what I might have done to myself otherwise.

Much of my bullheadedness, I knew, came as a result of losing my sister. After Pary's untimely death, life became more real. People can say things to you like, “You never know when your number's going to come up,” but it doesn't really mean much until you have someone you love taken away from you unexpectedly. From that day on, my delusions of immortality ended. Every minute now mattered. There were no second chances with life; you really

didn't

know when your number would come up. Failure was insufferable to me. I had no time to waste failing.

didn't

know when your number would come up. Failure was insufferable to me. I had no time to waste failing.

“Let's pack it up,” I said glumly. “We're a long way from home.”

I felt awful. The list of those I'd disappointed was long. Not only had I let down everyone who had supported me along the way, I had put my family in harm's way and had nothing to show for this imprudence but a broken heart and shin splints. Worst of all, I had failed my sister, my greatest inspiration.

Had I let myself down? The pain ran much deeper than that. I wasn't even worthy of consideration. I didn't matter. I was nothing more than a loathsome creature undeserving of the least bit of sympathy. Mere self-pity was three rungs above the dark hole where I resided. My honor was shattered.

During the long drive home with my family, there was ample time to reflect on the lessons from Badwater, and I eased up on myself. Yes, I had failedâbut it had actually been a spectacular failure, gloriously disintegrating every aspect of my body and soul until I literally fell over in the dirt. In the words of Theodore Roosevelt:

The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

Boy, did I know defeat. There was really no defeat more devastating than running oneself into the ground short of the finish line. I'd gone head to head with the world's toughest footrace, and lost. Despite my greatest efforts, Badwater had pounded me into submission.

It was pure, unadulterated defeat. But what I came to realize on the drive home was that I'd loved every second of it.

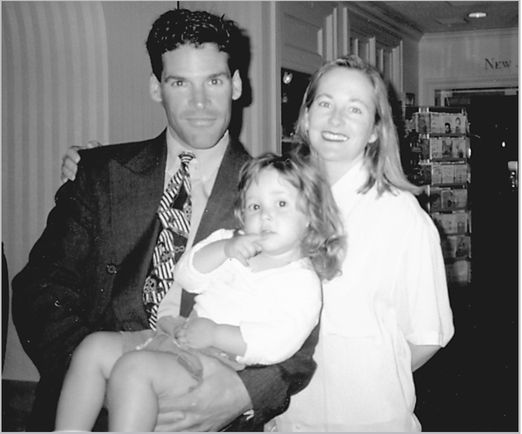

Alive and back home after Badwater with Julie and Alexandria

Chapter 12

Frozen Stiff

Only those who will risk going too far can

possibly find out how far they can go.

possibly find out how far they can go.

âT. S. Eliot

The South Pole January 2002After failing at Badwater

in 1995, I went back the next summer to seek redemption. This time around I trained even harder, bracing my body for the punishment I knew it would encounter along the way. The pounding was no less severe than in the first attempt, but my body and will surmounted the abuse this time, and I made it. However, succeeding at Badwater didn't satiate my hunger for adventure; it fed it.

in 1995, I went back the next summer to seek redemption. This time around I trained even harder, bracing my body for the punishment I knew it would encounter along the way. The pounding was no less severe than in the first attempt, but my body and will surmounted the abuse this time, and I made it. However, succeeding at Badwater didn't satiate my hunger for adventure; it fed it.

I embarked on a search-and-enjoy mission, throwing myself at any extreme endurance test that could be devised. If it required strength, stamina, and a lack of better judgment, I was game. I scaled Yosemite's infamous Half Dome, swam across the San Francisco Bay, did triathlons, adventure races, and twenty-four-hour mountain-bike rides. I climbed mountains, snowboarded down mountains, and surfed the massive liquid mountains off Northern California, Maui, Fiji, and Tahiti. And I continued to run like a wildman: running, to me, remained the purest form of athletic expression. It was the simplest, least encumbered sport there was, and the definitive measurement of raw stamina.

Other books

Troublemaker by Joseph Hansen

Cervantes Street by Jaime Manrique

Serial: Volume Two by Jaden Wilkes, Lily White

Dogwood by Chris Fabry

The Shark Rider by Ellen Prager

The Free (P.S.) by Vlautin, Willy

Go Kill Crazy! by Bryan Smith

Engaging Father Christmas by Robin Jones Gunn

Dragonfly Kisses by Sabrina York

Wizard's Education (Book 2) by James Eggebeen