UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY (62 page)

Read UMBERTO ECO : THE PRAGUE CEMETERY Online

Authors: Umberto Eco

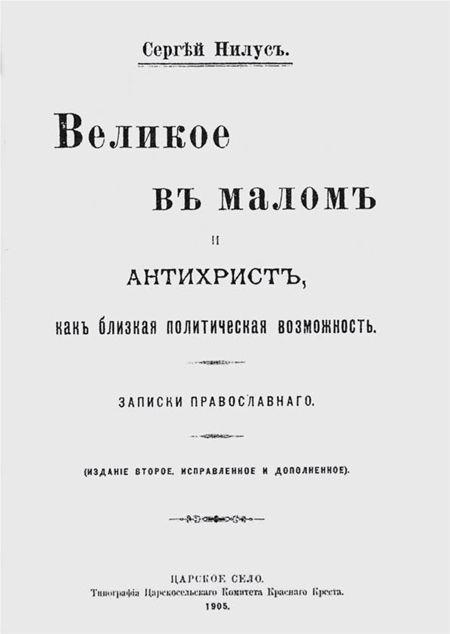

First edition of

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,

which

appeared in

The Great Within the Small

by Sergei Nilus

1905

The Great Within the Small, by Sergei Nilus, appears in Russia

, with the following introduction: "A personal friend, now dead, gave me a manuscript that, with unusual perfection and clarity, describes the course and development of a sinister world conspiracy . . . This document came into my hands around four years ago along with the absolute guarantee that it is the genuine translation of (original) documents stolen by a woman from one of the most powerful leaders and highest initiates of Freemasonry . . . The theft was carried out at the end of a secret assembly of 'Initiates' in France — a country that is the nest of the 'Jewish Masonic Conspiracy.' I venture to reveal this manuscript, for those who wish to see and listen, under the title of

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion."

The Protocols is immediately translated into many languages.

1921

The Times

of London finds similarities between the Protocols and Joly's book and denounces the Protocols as false, but it continues to be published as genuine.

1925 Adolf Hitler,

Mein Kampf

(I, 11): "How much the whole existence of this people is based on a permanent falsehood is apparent in the famous

Protocols of the Elders of Zion

. Every week the

Frankfurter Zeitung

whines that they are based on a forgery: and here lies the best proof that they are genuine . . . When this book becomes the common heritage of all people, the Jewish peril can then be considered as stamped out."

1939 In

L'Apocalypse de notre temps, Henri Rollin writes

: "[

The Protocols

] can be regarded as the most widely circulated work in the world after the Bible."

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

———————————————————————

p. 125:

Victory at Calatafimi,

1860 © Mary Evans Picture Library.

p. 163: Honoré Daumier,

Un jour où l'on ne paye pas

(Members of the Public at the Salon, 10, for

Le Charivari

), 1852 © Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

p. 347: Honoré Daumier,

Et dire qu'il y a des personnes qui boivent de l'eau dans un pays qui produit du bon vin comme celui-ci! (Croquis parisiens for Le journal amusant)

, 1864 © Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

p. 370:

The Traitor: The Degradation of Alfred Dreyfus

from the cover of

Le Petit Journal,

January 13, 1895, engraving by Henri Meyer, Private Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library.

All other illustrations are from the author's collection.

More by Eco:

Baudolino

Five Moral Pieces

Foucault's Pendulum

How to Travel with a Salmon & Other Essays

The Island of the Day Before

Kant and the Platypus

Misreadings

On Literature

The Name of the Rose

Please enjoy this sample chapter of

The Name of the Rose

by best-selling author Umberto Eco.

I

n the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. This was beginning with Go d and the duty of every faithful monk would be to repeat every day with chanting humility the one never-changing event whose incontrovertible truth can be asserted. But we see now through a glass darkly, and the truth, before it is revealed to all, face to face, we see in fragments (alas, how illegible) in the error of the world, so we must spell out its faithful signals even when they seem obscure to us and as if amalgamated with a will wholly bent on evil.

Having reached the end of my poor sinner's life, my hair now white, I grow old as the world does, waiting to be lost in the bottomless pit of silent and deserted divinity, sharing in the light of angelic intelligences; confined now with my heavy, ailing body in this cell in the dear monastery of Melk, I prepare to leave on this parchment my testimony as to the wondrous and terrible events that I happened to observe in my youth, now repeating verbatim all I saw and heard, without venturing to seek a design, as if to leave to those who will come after (if the Antichrist has not come first) signs of signs, so that the prayer of deciphering may be exercised on them.

May the Lord grant me the grace to be the transparent witness of the happenings that took place in the abbey whose name it is only right and pious now to omit, toward the end of the year of our Lord 1327, when the Emperor Louis came down into Italy to restore the dignity of the Holy Roman Empire, in keeping with the designs of the Almighty and to the confusion of the wicked usurper, simoniac, and heresiarch who in Avignon brought shame on the holy name of the apostle (I refer to the sinful soul of Jacques of Cahors, whom the impious revered as John X X I I ) .

Perhaps, to make more comprehensible the events in which I found myself involved, I should recall what was happening in those last years of the century, as I understood it then, living through it, and as I remember it now, complemented by other stories I heard afterward — if my memory still proves capable of connecting the threads of happenings so many and confused.

In the early years of that century Pope Clement V had moved the apostolic seat to Avignon, leaving Rome prey to the ambitions of the local overlords: and gradually the holy city of Christianity had been transformed into a circus, or into a brothel, riven by the struggles among its leaders; though called a republic, it was not one, and it was assailed by armed bands, subjected to violence and looting. Ecclesiastics, eluding secular jurisdiction, commanded groups of malefactors and robbed, sword in hand, transgressing and organizing evil commerce. How was it possible to prevent the Caput Mundi from becoming again, and rightly, the goal of the man who wanted to assume the crown of the Holy Roman Empire and restore the dignity of that temporal dominion that had belonged to the Caesars?

Thus in 1314 five German princes in Frankfurt elected Louis the Bavarian supreme ruler of the empire. But that same day, on the opposite shore of the Main, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, and the Archbishop of Cologne elected Frederick of Austria to the same high rank. Two emperors for a single throne and a single pope for two: a situation that, truly, fomented great disorder. . . .

Two years later, in Avignon, the new Pope was elected, Jacques of Cahors, an old man of seventy-two who took, as I have said, the name of John XXII , and heaven grant that no pontiff take again a name now so distasteful to the righteous. A Frenchman, devoted to the King of France (the men of that corrupt land are always inclined to foster the interests of their own people, and are unable to look upon the whole world as their spiritual home), he had supported Philip the Fair against the Knights Templars, whom the King accused (I believe unjustly) of the most shameful crimes so that he could seize their possessions with the complicity of that renegade ecclesiastic.

In 1322 Louis the Bavarian defeated his rival Frederick. Fearing a single emperor even more than he had feared two, John excommunicated the victor, who in return denounced the Pope as a heretic. I must also recall how, that very year, the chapter of the Franciscans was convened in Perugia, and the minister general, Michael of Cesena, accepting the entreaties of the Spirituals (of whom I will have occasion to speak), proclaimed as a matter of faith and doctrine the poverty of Christ, who, if he owned something with his apostles, possessed it only as usus facti. A worthy resolution, meant to safeguard the virtue and purity of the order, it highly displeased the Pope, who perhaps discerned in it a principle that would jeopardize the very claims that he, as head of the church, had made, denying the empire the right to elect bishops, and asserting on the contrary that the papal throne had the right to invest the emperor. Moved by these or other reasons, John condemned the Franciscan propositions in 1323 with the decretal

Cum inter nonnullos.