Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (13 page)

Read Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco Online

Authors: Judy Yung

Even those with the legal right to immigrate sometimes failed to pass

the difficult interrogations and physical examinations required only of

Chinese immigrants.22 Aware of the intimidating entry procedures, many were discouraged from even trying to immigrate. Many Chinese Americans shared the sentiments of Pany Lowe, an American-born Chinese

man who was interviewed in 1924:

Sure I go back to China two times. Stay ten or fifteen months each time.

I do not want to bring my wife to this country. Very hard get her in. I

know how immigration inspector treat me first time when I come back

eighteen years old.... My father have to go to court. They keep me on

boat for two or three days. Finally he got witness and affidavit prove me

to be citizen. They let me go, so I think if they make trouble for me they

make trouble for my wife.... I think most Chinese in this country like

have their son go China get married. Under this new law [Immigration

Act of 1924], can't do this. No allowed marry white girl. Not enough

American-born Chinese to go around. China only place to get wife. Not

allowed to bring them back. For Chinaman, very unjust. Not human.

Very uncivilized.23

American immigration laws and the process of chain migration also

determined that most Chinese women would continue to come from

the rural villages of Guangdong Province, where traditional gender roles

still prevailed. Wong Ah So and Law Shee Low, both of whom immigrated in 1922, serve as examples of Guangdong village women who

came as obedient daughters or wives to escape poverty and for the sake

of their families. Jane Kwong Lee, who also came to the United States

in 1922, was among the small number of urbanized "new women" who

emigrated on their own for improved opportunities and adventure. Together, these three women's stories provide insights into the gender roles

and immigration experiences of Chinese women in the early twentieth

century.

"I was born in Canton [Guangdong] Province," begins Wong Ah So's

story, "my father was sometimes a sailor and sometimes he worked on

the docks, for we were very poor."24 Patriarchal cultural values often put

the daughter at risk when poverty strikes: from among the five children

(two boys and three girls) in the family, her mother chose to betroth

her, the eldest daughter, to a Gold Mountain man in exchange for a bride

price of 450 Mexican dollars.

I was 19 when this man came to my mother and said that in America

there was a great deal of gold. Even if I just peeled potatoes there, he

told my mother I would earn seven or eight dollars a day, and if I was

willing to do any work at all I would earn lots of money. He was a laundryman, but said he earned plenty of money. He was very nice to me, and my mother liked him, so my mother was glad to have me go with

him as his wife.25

Out of filial duty and economic necessity, Ah So agreed to sail to the

United States with this laundryman, Huey Yow, in 1922: "I was told by

my mother that I was to come to the United States to earn money with

which to support my parents and my family in Hongkong."26 Sharing

the same happy thoughts about going to America as many other immigrants before her, she said, "I thought that I was his wife, and was very

grateful that he was taking me to such a grand, free country, where everyone was rich and happy."27

Huey Yow had a marriage certificate prepared and told her to claim

him as her husband to the immigration officials in San Francisco, although there had been no marriage ceremony. "In accordance to my

mother's demands I became a party to this arrangement," Ah So admitted later. "On my arrival at the port of San Francisco, I claimed to

be the wife of Huey Yow, but in truth had not at any time lived with

him as his wife."28

Law Shee Low (Law Yuk Tao was her given name before marriage),

who was a year younger than Wong Ah So, was born in the village of

Kai Gok in Chungshan District, Guangdong Province.29 Economic and

political turmoil in the country hit her family hard. Once well-to-do,

they were reduced to poverty in repeated raids by roving bandits. As

Law recalled, conditions became so bad that the family had to sell their

land and give up their three servants; all four daughters had to quit school

and help at home.

My grandmother, mother, and an aunt all had bound feet, and it was so

painful for them to get around. When they got up in the morning, I had

to go fetch the water for them to wash up and carry the night soil buckets out. Every morning, we had to draw water from the well for cooking, for tea, and for washing. I would help grandmother with the cooking, and until I became older, I was the one who went to the village

marketplace every day to shop.

Along with one other sister, Law was also responsible for sweeping the

floor, washing dishes, chopping wood, tending the garden, and scrubbing the brick floor after each rainfall. In accordance with traditional gender roles, none of her brothers had to help. "They went to school. It

was work for girls to do," she said matter-of-factly.

As in the case of Wong Ah So, cultural values and economic necessity led her parents to arrange a marriage for Law with a Gold Moun tain man. Although aware of the sad plight of other women in her village who were married to Gold Mountain men-her own sister-in-law

had gone insane when her husband in America did not return or send

money home to support her-Law still felt fortunate: she would be going to America with her husband.

I had no choice; we were so poor. If we had the money, I'm sure my

mother would have kept me at home.... We had no food to go with

rice, not even soy sauce or black bean paste. Some of our neighbors even

had to go begging or sell their daughters, times were so bad.... So my

parents thought I would have a better future in Gold Mountain.

Her fiance said he was a clothing salesman in San Francisco and a Christian. He had a minister from Canton preside over the first "modern"

wedding in his village. Law was eighteen and her husband, thirty-four.

Nine months after the wedding, they sailed for America.

Jane Kwong Lee was born in the same region of China (Op Lee Jeu

village, Toishan District, Guangdong Province) at about the same time

(19o2). But in contrast to Law Shee Low and Wong Ah So, she came

from a higher-class background and emigrated under different circumstances. Her life story, as told in her unpublished autobiography, shows

how social and political conditions in China made "new women" out of

some like herself. Like Law and Ali So, Jane grew up subjected to the

sexist practices of a patriarchal society. Although her family was not poor,

her birth was not welcomed.

I was the second daughter, and two girls in a row were one too many,

according to my grandparents. Girls were not equal to boys, they maintained. Girls, after they married, belonged to other families; they could

not inherit the family name; they could not help the family financially no

matter how good they were at housework. In this atmosphere of emotional depression I was an unwanted child, and to add to the family sadness the weather seemed to be against me too. There was a drought, the

worst drought in many years, and all the wells dried up except one. Water had to be rationed. My long (youngest) uncle went out to get the

family's share daily. The day after I was horn, the man at the well gave

him the usual allotment, but my uncle insisted on obtaining one more

scoop. The man asked why and the answer was, "We have one more

mouth." Then, and only then, the villagers became aware that there had

been a baby born in their midst. My grandparents were ashamed of having two granddaughters consecutively and were reluctant to have their

neighbors know they had one more person in their family. They wanted

grandsons and hoped for grandsons in the future. That is why they named

me "Lin Hi," meaning "Link Young Brother." They believed in good omens and I did not disappoint them. My brother was born a year and

a half later.30

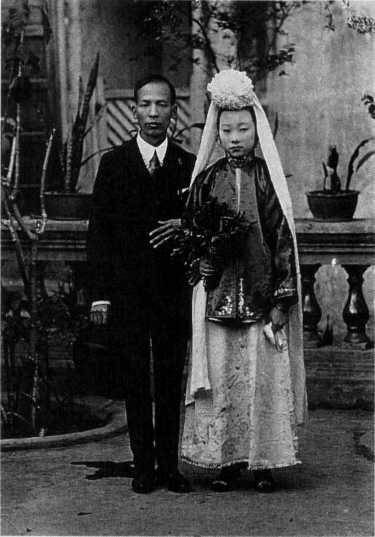

Wedding portrait of Law Shee

Low and husband Low Gun

(a.k.a. Low Gar Chong),

Heungshan (now Zhongshan)

District, Guangdong Province,

China, 19zi. (Courtesy of

Law Shee Low)

Compared to Law's hard-working childhood, Jane lived a carefree life,

playing hide-and-seek in the bamboo groves, catching sparrows and

crabs, listening to ghost stories, and helping the family's mui tsai tend

the vegetable garden. It was a life punctuated by holiday observances

and celebrations of new births and marriages as well as the turmoil of

family illnesses and deaths, droughts and floods, political uprisings and

banditry.

Like Law, Jane came from a farming background. Her grandfather

was successful in accumulating land, which he leased out to provide for

the family. Her uncle and father were businessmen in Australia; their remittances made the difference in helping the family weather natural disasters and banditry and provided the means by which Jane was able to

acquire an education at True Light Seminary in Canton. Social reforms

and progressive views on women's equality at the time also helped to

make her education possible:

Revolution was imminent. Progress was coming. Education for girls was

widely advocated. Liberal parents began sending their daughters to

school. My long [youngest] aunt, sixth aunt-in-law, godsister Jade and

cousin Silver went to attend the True Light Seminary in Canton. Women's

liberation had begun. It was the year 191 i-the year the Ching [Qing]

Dynasty was overthrown and the Republic of China was born.31

Her parents were among the liberal ones who believed that daughters

should be educated if family means allowed it. Her father had become

a Christian during his long sojourn in Australia, and her mother was the

first in their village to unbind her own feet. From the age of nine, Jane

attended True Light, a boarding school for girls and women sponsored

by the Presbyterian Missionary Board in the United States. She completed her last year of middle school at the coeducational Canton Christian College. It was during this time that she adopted the Western name

Jane. By then, "the Western wind was slowly penetrating the East and

old customs were changing," she wrote.32

The curriculum stressed English and the three R's-reading, writing,

and arithmetic-but also included classical Chinese literature. In addition, students had the opportunity to work on the school journal, learn

Western music appreciation, and participate in sports-volleyball, baseball, and horseback riding. The faculty, all trained in the United States,

exposed students to Western ideas of democracy and women's emancipation. During her last year in school, Jane, along with her classmates,

was swept up by the May Fourth Movement, in which students agitated

for political and cultural reforms in response to continuing foreign domination at the end of World War I:

The zi demands from Japan stirred up strong resentment from the students as well as the whole Chinese population. We boycotted Japanese

goods and bought only native-manufactured fabrics. We participated in

demonstration parades in the streets of Canton. Student delegates were

elected to attend student association discussion meetings in Canton; once

I was appointed as one of two delegates from our school. Our two-fold

duty was to take part in the discussions and decisions and then to convince our schoolmates to take active parts in whatever action was decided.

It was a year of turmoil for all the students and of exhaustion for me.33

By the time she graduated from middle school, Jane had decided she

wanted to become a medical doctor, believing "it would give me not

only financial independence, but also social prestige."34 Her only other

choices at the time were factory work or marriage. But further education seemed out of the question because her father's remittances from Australia could no longer support the education of both Jane and her

younger brother. Arguing that graduates trained in American colleges

and universities were drawing higher salaries in China than local graduates, Jane convinced her mother to sell some of their land in order to

pay her passage to the United States. Her mother also had hopes that

she would find work teaching at Chinese schools in America and be able

to send some of her income home. In 19zz, Jane obtained a student

visa and sailed for the United States, planning to earn a doctorate and

return home to a prestigious academic post. Her class background, education, and early exposure to Western ideas would lead her to a different life experience in America than Law Shee Low and Wong Ah So,

who came as obedient wives from sheltered and impoverished families.

Detainment at Angel Island