Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption (41 page)

Read Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption Online

Authors: Laura Hillenbrand

Tags: #Autobiography.Historical Figures, #History, #Biography, #Non-Fiction, #War, #Adult

“It is difficult to rejoice outwardly (though I do in my heart) when I think of the other mothers whom I have learned to love, and realize how keenly they feel the loss that is theirs,” Kelsey wrote to Louise. “How my heart goes out to them and I shal write them every one.”

——

As Christmas neared, Louie faltered. Starvation was consuming him. The occasional gifts from the thieves helped, but not enough. What was most maddening was that ample food was so near. Twice that fal , Red Cross relief packages had been delivered for the POWs, but instead of distributing them, camp officials had hauled them into storage and begun taking what they wanted from them.* They made no effort to hide the stealing. “We could see them throwing away unmistakable wrappers, carrying bowls of bulk cocoa and sugar between huts and even trying to wash clothes with cakes of American cheese,” wrote Tom Wade. The Bird was the worst offender, smoking Lucky Strike cigarettes and openly keeping Red Cross food in his room.

From one delivery of 240 Red Cross boxes, the Bird stole forty-eight, more than five hundred pounds of goods.

Toward the end of December, the Bird ordered al of the men to the compound, where they found a truck brimming with apples and oranges. In al of his time as a POW, Louie had seen only one piece of fruit, the tangerine that Sasaki had given him. The men were told that they could take two pieces each.

As the famished men swarmed onto the pile, Japanese photographers circled, snapping photos. Then, just as the men were ready to devour the fruit, the order came to put it al back. The entire thing had been staged for propaganda.

On Christmas Eve, some Red Cross packages were final y handed out. Louie wrote triumphantly of it in his diary. His box, weighing some eleven pounds, contained corned beef, cheese, pâté, salmon, butter, jam, chocolate, milk, prunes, and four packs of Chesterfields. Al evening long, the men of Omori traded goods, smoked, and gorged themselves.

That night, there was another treat, and it came about as the result of a series of curious events. Among the POWs was a chronical y unwashed, ingenious, and possibly insane kleptomaniac named Mansfield. Shortly before Christmas, Mansfield broke into the storehouse—slipping past seven guards—and made off with several Red Cross packages, which he buried under his barracks. Discovering his cache, guards locked him in a cel .

Mansfield broke out, stole sixteen more parcels, and snuck them back into his cel . He hid the contents of the packages in a secret compartment he’d fashioned himself, marking the door with a message for other POWs: Food, help yourself, lift here. Caught again, he was tied to a tree in the snow without food or water, wearing only pajamas, and beaten. By one account, he was left there for ten days. Late one night, when Louie was walking back from the benjo, he saw the camp interpreter, Yukichi Kano, kneeling beside Mansfield, draping a blanket over him. The next morning, the blanket was gone, retrieved before the Bird could see it. Eventual y, Mansfield was untied and taken to a civilian prison, where he flourished.

The one good consequence of this event was that in the storehouse, Mansfield had discovered a Red Cross theatrical trunk. He told other POWs about it, and this gave the men the idea of boosting morale by staging a Christmas play. They secured the Bird’s approval by stroking his ego, naming him

“master of ceremonies” and giving him a throne at the front of the “theater”—the bathhouse—outfitted with planks perched on washtubs to serve as a stage. The men decided to put on a musical production of Cinderella, written, with creative liberties, by a British POW. Frank Tinker put his operatic gifts to work as Prince Leander of Pantoland. The Fairy Godmother was played by a mountainous cockney Brit dressed in a tutu and tights. Characters included Lady Dia Riere and Lady Gonna Riere. Louie thought it was the funniest thing he’d ever seen. Private Kano translated for the guards, who sat in the back, laughing and clapping. The Bird gloried in the limelight, and for that night, he let Louie and the others be.

At Zentsuji, Christmas came to Phil and Fred Garrett. Some POWs scrounged up musical instruments and assembled in the camp. Before seven hundred starving men, they played rousing music as the men sang along. They ended with the national anthems of England, Hol and, and the United States. The Zentsuji POWs stood together at attention in silence, thinking of home.

——

After Christmas, the Bird abruptly stopped attacking the POWs, even Louie. He paced about camp, brooding. The men watched him and wondered what was going on.

Several times that year, a dignitary named Prince Yoshitomo Tokugawa had come to camp. A prominent and influential man, reportedly a descendant of the first shogun, Tokugawa was touring camps for the Japanese Red Cross. At Omori, he met with POW Lewis Bush, who told him about the Bird’s cruelty.

The Bird was suspicious. After Tokugawa first visited, the Bird forbade Bush from speaking to him again. When the prince returned, Bush defied the Bird, who beat him savagely as soon as the prince left. Tokugawa kept coming, and Bush kept meeting with him. The Bird slugged and kicked Bush, but Bush refused to be cowed. Deeply troubled by what he heard, Tokugawa went to the war office and the Red Cross and pushed to have something done about Watanabe. He told Bush that he was encountering resistance. Then, just before the New Year, the prince at last succeeded. The Bird was ordered to leave Omori.

Tokugawa’s victory was a hol ow one. Officials made no effort to take the Bird out of contact with POWs. They simply ordered his transfer to a distant, isolated camp, where he’d have exactly the same sway over prisoners, without the prying eyes of the prince and the Red Cross. Ensuring that no censure of Watanabe was implied, Colonel Sakaba promoted him to sergeant.

The Bird threw himself a good-bye party and ordered some of the POW officers to come. The officers dashed around camp to gather stool samples from the greenest dysentery patients, mixed up a ferocious gravy, and slathered it over a stack of rice cakes. When they arrived at the party, they presented the cakes to the Bird as a token of their affection. While the men lavished the Bird with lamentations on how they’d miss him, the Bird ate heartily. He seemed heartbroken to be leaving.

Later that day, Louie looked out of the barracks and saw the Bird standing by the gate in a group of people, shaking hands. Al of the POWs were in a state of high animation. Louie asked what was happening, and someone told him that the Bird was leaving for good. Louie felt almost out of his head with joy.

If the rice cakes performed as engineered, they didn’t do so quickly. The Bird crossed the bridge onto the mainland, looking perfectly wel . At Omori, the reign of terror was over.

* Phil had no such potential usefulness but was probably spared because his execution would have made Louie less likely to cooperate.

* After the war, the head of the Tokyo area camps would admit that he had ordered the distribution of Red Cross parcels to Japanese personnel.

Twenty-seven

Falling Down

AT OMORI, LIFE BECAME IMMEASURABLY BETTER. PRIVATE Kano quietly took over the camp, working with Watanabe’s replacement, Sergeant Oguri, a humane, fair-minded man. The Bird’s rules were abolished. Someone got into the Bird’s office and found a pile of mail sent to the POWs by their families. Some of the letters had been in his office for nine months. The letters were delivered, and the POWs were final y al owed to write home. “Trust you’re al in good health and in the highest of spirits, not the kind that comes in bottles,” Louie wrote in one letter to his family. “Tel Pete,” he wrote in another, “that when I’m 50, I’l have more hair on my head than he had at 20.” The letters, like so many others, languished in the glacial mail system, and wouldn’t make it to America until long after the war’s end.

Two weeks into 1945, a group of men, tattered and bent, trudged over the bamboo bridge and into Omori. Louie knew their faces: These were Ofuna men. Commander Fitzgerald was with them. The Omori prisoners told him that he was the luckiest man in Japan. A vicious tyrant cal ed the Bird had just left.

Among the new POWs, Louie spotted Bil Harris, and his heart fel . Harris was a wreck. When Louie greeted him, his old friend looked at him vaguely.

He was hazy and distant, his mind struggling for purchase on his thoughts.

The beating the Quack had delivered to Harris in September 1944 hadn’t been the last. On November 6, apparently after Harris was caught speaking, the Quack had pounced on him again, joining several guards in clubbing him into unconsciousness. Two months later, Harris had been beaten once more, for stealing nails to repair his torn shoes, which he was trying to nurse through a frigid winter. He had asked the Japanese to give him some, but they had refused.

The Omori POW doctor examined Harris gravely. He told Louie that he thought the marine was dying.

That same day, Oguri opened the storehouse and had the Red Cross boxes handed out. Giving his box to Harris was, Louie would say, the hardest and easiest thing he ever did. Harris ral ied.

Since his refusal to become a propaganda prisoner, Louie had been waiting to be shipped to punishment camp. While the Bird had badgered him, he had awaited his fate with equanimity. Now that the Bird was gone, and Harris was here with Louie’s other friends, Louie wanted to stay. He met every day with dread, awaiting his transfer.

——

The B-29s kept coming. Sirens sounded several times a day. Rumors eddied around camp: Manila had been captured, Germany had fal en, the Americans were about to charge the Japanese beaches. Louie, like a lot of POWs, was worried. Frightened by the bombing, the guards were increasingly jumpy and angry. Even guards who had once been amiable were now hostile, lashing out without reason. As the assaults on Japan intensified and the probability of invasion rose, the Japanese seemed to view the POWs as threatening.

Among the American forces, a horrifying piece of news had just surfaced. One hundred and fifty American POWs had long been held on Palawan Island, in the Philippines, where they’d been used as slaves to construct an airfield. In December, after American planes bombed the field, the POWs were ordered to dig shelters. They were told to build the entrances only one man wide.

On December 14, an American convoy was spotted near Palawan. The commander of the Japanese 2nd Air Division was apparently sure that the Americans intended to invade. It was the scenario for which the kil -al order had been written. That night, the commander sent a radio message to Palawan: “Annihilate the 150 prisoners.”

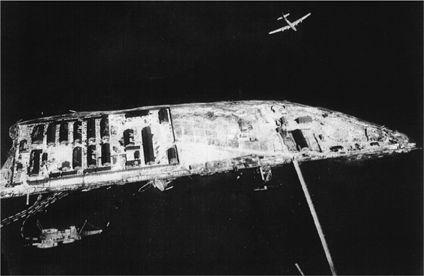

A B-29 over the Omori POW camp. Raymond Halloran

On December 15 on Palawan, the guards suddenly began screaming that there were enemy planes coming. The POWs crawled into the shelters and sat there, hearing no planes. Then liquid began to rain onto them. It was gasoline. The guards tossed in torches, then hand grenades. The shelters, and the men inside, erupted in flames.

As the guards cheered, the POWs fought to escape, some clawing their own fingertips off. Nearly al of those who broke out were bayoneted, machine-gunned, or beaten to death. Only eleven men escaped. They swam across a nearby bay and were discovered by inmates at a penal colony. The inmates delivered them to Filipino guerril as, who brought them to American forces.

That night, the Japanese threw a party to celebrate the massacre. Their anticipation of an American landing turned out to be mistaken.

——

Sleet was fal ing over Omori as February 16 dawned. At seven-fifteen, Louie and the other POWs had just finished a breakfast of barley and soup when the sirens piped up. Commander Fitzgerald looked at his friends. He knew that this would probably not be B-29s, which would have had to fly al night to reach Japan so early. It was probably carrier aircraft: His navy must be near. A few seconds later, the room was shaking. The men bolted for the doors.

Louie ran out into a crashing, tumbling world. The entire sky was swarming with hundreds of fighters, American and Japanese, rising and fal ing, streaming bul ets at one another. Over Tokyo, lines of dive-bombers bel ied down like waves slapping a beach, slamming bombs into the aircraft works and airport. As they rose, quil s of fire came up under them. Louie was standing directly underneath the largest air battle yet fought over Japan.

The guards fixed their bayonets and ordered the POWs back inside. Louie and the others filed into the barracks, waited for the guards to rush off to censure someone else, then stole out. They ran behind a barracks, climbed the camp fence, and hung there, resting their elbows on the top. The view was electrifying. Planes were sweeping over every corner of the sky, and al around, fighters were dropping into the water.

One dogfight riveted Louie’s attention. An American Hel cat hooked up with a Japanese fighter and began chasing it. The Japanese fighter turned toward the city and dove low over the bay, the Hel cat right behind it. The two planes streaked past the camp, the Japanese fighter racing flat out, the Hel cat’s guns firing. Several hundred POWs watched from the camp fence, their eyes pressed to knotholes or their heads poking over the top, hearts leaping, ears roaring. The fighters were so close that Louie could see both pilots’ faces. The Japanese fighter crossed over the coast, and the Hel cat broke away.