Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption (49 page)

Read Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption Online

Authors: Laura Hillenbrand

Tags: #Autobiography.Historical Figures, #History, #Biography, #Non-Fiction, #War, #Adult

—were stil alive. Louie and Phil had vanished in the Pacific. Deasy had gone home with tuberculosis. Only Stay had completed his forty-mission tour of duty. He’d seen five planes on his wing go down, with every man kil ed, and yet somehow, the sum total of damage to his bombers was one bul et hole.

He’d gone home in March.

Someone brought Louie the August 15 issue of the Minneapolis Star-Journal. Near the back was an article entitled “Lest We Forget,” discussing athletes who had died in the war. More than four hundred amateur, professional, and col egiate athletes had been kil ed, including nineteen pro footbal players, five American League basebal players, eleven pro golfers, and 1920 Olympic champion sprinter Charlie Paddock, whom Louie had known.

There on the page with them, Louie saw his own picture and the words “great miler … kil ed in action in the South Pacific.”

The Okinawa mess hal was kept open around the clock for the POWs, who couldn’t stop eating. Louie headed straight for it, but was stopped at the door. Because the Japanese had never registered him with the Red Cross, his name wasn’t on the roster. As far as the mess was concerned, Louie

wasn’t a POW. He encountered the same problem when trying to get a new uniform to replace the pants and shirt that he had worn every day since May 27, 1943. Until the snafu was straightened out, he had to subsist on candy bars from Red Cross nurses.

Soon after Louie’s arrival, he was sent to a hospital to be examined. Like most POWs, in gorging day and night, he had gained weight extremely rapidly; he now weighed 143 pounds, just seventeen pounds under his weight at the time of the crash. But thanks to dramatic water retention, it was a doughy, moon-faced, muscleless weight. He stil had volatile dysentery and was as weak as a blade of grass. He was only twenty-eight, but his body, within and without, was etched with the trauma of twenty-seven months of abuse and deprivation. The physicians, who knew what Louie had once been, sat him down to have a solemn talk. After Louie left the doctors, a reporter asked him about his running career.

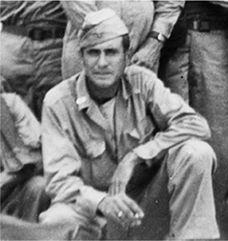

Louie in Okinawa. On his right hand is the USC class ring that caught in the wreckage of his plane as it sank. Courtesy of Louis Zamperini

“It’s finished,” he said, his voice sharp. “I’l never run again.”

——

The Zamperinis were on edge. Since Louie’s crash, his only message to make it to America had been his radio broadcast ten months earlier. The letters that he had written after the Bird had left Omori had not arrived. Other than the War Department’s December confirmation that Louie was a POW, no further word from or about him had come. The papers were ful of stories about the murder of POWs, and families couldn’t rest easy. The Zamperinis contacted the War Department, but the department had nothing to tel . Sylvia kept writing to Louie, tel ing him of al they would do when he came home.

“Darling, we wil take the best of care for you,” she wrote. “You shal be ‘King Toots,’—anything your heart desires—(yes, even red heads and al ).” But she, like the rest of the family, was scared. Pete, living in his officer’s quarters in San Diego, kept cal ing home to see if news had come. The answer was always no.

On the morning of September 9, Pete was startled awake by a hand on his shoulder, shaking him vigorously. He opened his eyes to see one of his friends bending over him with a huge smile. Trumbul ’s story had appeared in the Los Angeles Times. The headline said it al : ZAMPERINI COMES BACK FROM

DEAD.

In a moment, Pete was on his feet, throwing on his clothes. He bolted for a telephone and dialed his parents’ number. Sylvia picked up. Pete asked if she had heard the news.

“Did you hear the news?” she repeated back to him. “Did I! Wow!” Pete asked to speak to his mother, but she was too overcome to talk.

Louise and Virginia rushed to church to give thanks, then raced home to prepare the house. As she stood in Louie’s room, dusting his running trophies, Louise blinked away tears, singing out, “He’s on the way home. He’s on the way home.”

“From now on,” she said, “September 9 is going to be Mother’s Day to me, because that’s the day I learned for sure my boy was coming home to stay.”

“What do you think, Pop?” someone asked Louie’s father.

“Those Japs couldn’t break him,” Anthony said. “My boy’s pretty tough, you know.”

——

Liberation was a long time coming for Phil and Fred at Rokuroshi. After the August 22 announcement of the war’s end, the POWs sat there, waiting for someone to come get them. They got hold of a radio, and on it they heard chatter from men liberating other camps, but no one came for them. They began to wonder if anyone knew they were there. It wasn’t until September 2 that B-29s final y flew over Rokuroshi, their pal ets hitting the rice paddies with such force that the men had to dig them out. The POWs ate themselves sil y. One man downed twenty pounds of food in a single day, but somehow didn’t get sick.

That afternoon, an American navy man dug through his belongings and pul ed out his most secret and precious possession. It was an American flag with a remarkable provenance. In 1941, just before Singapore had fal en to the Japanese, an American missionary woman had given it to a British POW.

The POW had been loaded aboard a ship, which had sunk. Two days later, another British POW had rescued the flag from where it lay underwater and slipped it to the American navy man, who had carried it through the entire war, somehow hiding it from the Japanese, until this day. The POWs pul ed down the Japanese flag and ran the Stars and Stripes up the pole over Rokuroshi. The men stood before it, hands up in salutes, tears running down their faces.

On September 9, Phil, Fred, and the other POWs were final y trucked off the mountain. Arriving in Yokohama, they were greeted with pancakes, a band playing “California, Here I Come,” and a general who broke down when he saw them. The men were escorted aboard a ship for hot showers and more food. On September 11, the ship set off for home.

When news of the Trumbul story reached Indiana, Kelsey Phil ips’s telephone began ringing, and friends and reporters flocked onto her front porch.

Remembering the War Department’s request that she not speak publicly of her son’s survival, Kelsey kept a smiling silence, awaiting official notification that Al en had been released from the POW camp. It wasn’t until September 16 that the War Department telegram announcing Al en’s liberation reached her. It was fol owed by a phone cal from her sister, who delivered a message from Al en that had passed from person to person from Rokuroshi to Yokohama to San Francisco to New Jersey to Indiana: He was free. Al en’s friends went downtown and bought newspapers, spread them out on someone’s living room floor, and spent the morning reading and crying.

As she celebrated, Kelsey thought of what Al en had written in a letter to her. “I would give anything to be home with al of you,” the letter said, “but I’m looking forward to the day—whenever it comes.”

“That day,” Kelsey rejoiced, “has come.”

——

On Okinawa, Louie was having a grand time, eating, drinking, and making merry. When he was given orders to fly out, he begged a doctor to arrange for him to stay a little longer, on the grounds that he didn’t want his mother to see him so thin. The doctor not only agreed to have Louie “hospitalized,” he threw him a welcome-back-to-life bash, complete with a five-gal on barrel of “bourbon”—alcohol mixed with Coke syrup, distil ed water, and whatever else was handy.

More than a week passed, bombers left with loads of POWs, and stil Louie stayed on Okinawa. The nurses threw him another party, the ersatz bourbon went down easy, and there was a moonlit jeep ride with a pretty girl. Along the way, Louie discovered that a delightful upside to being believed dead was that he could scare the hel out of people. Learning that a former track recruiter from USC was on the island, he asked a friend to tel the recruiter that he had a col ege running prospect who could spin a mile in just over four minutes. The recruiter eagerly asked to meet the runner. When Louie appeared, the recruiter fel over backward in his chair.

On September 17, a typhoon hit Okinawa. Louie was in a tent when nature cal ed, sending him into the storm to fight his way to an outhouse. He was on the seat with his pants down when a wind gust shot the outhouse over an embankment, carrying Louie in it. Dumped in the mud under a downpour, Louie stood up, hitched up his pants, got broadsided by another gust, and fel over. He crawled through the mud, “lizarding his way,” as he put it, up the hil . He had to bang on the hospital door for a while before someone heard him.

The next morning dawned to find planes flipped over, ships sunk, tents col apsed. Louie, covered in everything that a somersault inside an outhouse wil slather on a man, was final y wil ing to leave Okinawa. He got an enlisted man to pour water over his head while he soaped off, then went to the airfield.

When he saw the plane that he was to ride in, he felt a swel of nausea. It was a B-24.

The first leg of the journey, to the Philippine city of Laoag, went without incident. On the second flight, to Manila, the plane was so overloaded with POWs that it nearly crashed just after takeoff, dipping so low that seawater sprayed the POWs’ legs through gaps in the bomb bay floor.* But the bomber made it to Manila, where Louie got passage out on a transport plane. He sat in the cockpit, tel ing the pilot his story, from the crash to Kwajalein to Japan.

As Louie spoke, the pilot dropped the plane down over an island and landed. The pilot asked Louie if he’d ever seen this place before. Louie looked around at a charred wasteland, recognizing nothing.

“This is Kwajalein,” said the pilot.

This couldn’t be Kwajalein, Louie thought. In captivity, glimpsing the island through gaps in his blindfold, or when being hustled to interrogation and medical experimentation, he’d seen a vast swath of intense green. Now, he couldn’t find a single tree. The fight for this place had ripped the jungle off the island. Louie would long wonder if kind-hearted Kawamura had died here.

Someone told him that there was, in fact, one tree stil standing. They borrowed a jeep and drove over to see it. Staring at Kwajalein’s last tree, with food in his bel y, no blindfold over his eyes, no one there to beat him, Louie felt as if he were in the sweetest of dreams.

On he went to Hawaii. Seeing the condition of the POWs, American authorities had decided to hospitalize virtual y al of them. Louie was checked into a Honolulu hospital, where he found himself rooming with Fred Garrett. It was the first time that Louie had slept on a mattress, with sheets, since the first days after his capture. He was given a new uniform and captain’s bars, having been promoted during his imprisonment, as most army POWs were. Trying on his new clothes, he pul ed off his beloved muslin shirt, set it aside, and forgot about it. He went downtown, then remembered the shirt and returned to retrieve it. It had been thrown away. He was heartbroken.

Louie and Fred hit the town. Seemingly everyone they met wanted to take them somewhere, feed them, buy them drinks. On a beach, they made a spectacle of themselves when Fred, feeling emasculated by the pity over his missing leg, flung away his crutches, hopped over to Louie, and tackled him.

The wrestling match drew a crowd of offended onlookers, who thought that an able-bodied soldier was beating up a helpless amputee. Swinging around Hawaii, getting drunk, knocking heads with Fred, Louie never left himself a moment to think of the war. “I just thought I was empty and now I’m being fil ed,”

he said later, “and I just wanted to keep being fil ed.”

——

That October, Tom Wade walked off a transport ship in Victoria, Canada. With a multitude of former POWs, he began a transcontinental rail journey that became a nonstop party, including eight impromptu weddings. “I must have kissed a thousand girls crossing the continent,” Wade wrote to Louie, “and when I walked through the train with lipstick al over my face after the first station, I was the most popular officer on the train.” In New York, he was taken aboard the Queen Elizabeth to sail for England. He snuck down the gangway, necked with a Red Cross girl, and stole back aboard toting a box of Hershey bars. When he reached England, he discovered that the local women preferred Yank and Canadian soldiers to Brits. “I decided to do something about it,” he wrote. “I sewed a couple of extra patches and oddments on to my uniform, nobody was any wiser, and stormed them. I did al right.”