Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption (55 page)

Read Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption Online

Authors: Laura Hillenbrand

Tags: #Autobiography.Historical Figures, #History, #Biography, #Non-Fiction, #War, #Adult

Cynthia was distraught over what her husband had become. In public, his behavior was frightening and embarrassing. In private, he was often prickly and harsh with her. She did her best to soothe him, to no avail. Once, while Louie was out, she painted their dreary kitchen with elaborate il ustrations of

vines and animals, hoping to surprise him. He didn’t notice.

Wounded and worried, Cynthia couldn’t bring Louie back. Her pain became anger, and she and Louie had bitter fights. She slapped him and threw dishes at him; he grabbed her so forceful y that he left her bruised. Once he came home to find that she had run through a room, hurling everything breakable onto the floor. While Cynthia cooked dinner during a party on a friend’s docked yacht, Louie was so snide to her, right in front of their friends, that she walked off the boat. He chased her down and grabbed her by the neck. She slapped his face, and he let her go. She fled to his parents’ house, and he went home alone.

Cynthia eventual y came back, and the two struggled on together. His money gone, Louie had to tap a friend for a $1,000 loan, staking his Chevy convertible as col ateral. The money ran out, another investment foundered, the loan came due, and Louie had to turn over his keys.

When Louie was a smal child, he had tripped and fal en on a flight of stairs while hurrying to school. He had gotten up, only to stumble and fal a second time, then a third. He had risen convinced that God himself was tripping him. Now the same thought dwelt in him. God, he believed, was toying with him.

When he heard preaching on the radio, he angrily turned it off. He forbade Cynthia from going to church.

In the spring of 1948, Cynthia told Louie that she was pregnant. Louie was excited, but the prospect of more responsibility fil ed him with guilt and despair. In London that summer, Sweden’s Henry Eriksson won the Olympic gold medal in the 1,500 meters. In Hol ywood, Louie drank ever harder.

No one could reach Louie, because he had never real y come home. In prison camp, he’d been beaten into dehumanized obedience to a world order in which the Bird was absolute sovereign, and it was under this world order that he stil lived. The Bird had taken his dignity and left him feeling humiliated, ashamed, and powerless, and Louie believed that only the Bird could restore him, by suffering and dying in the grip of his hands. A once singularly hopeful man now believed that his only hope lay in murder.

The paradox of vengefulness is that it makes men dependent upon those who have harmed them, believing that their release from pain wil come only when they make their tormentors suffer. In seeking the Bird’s death to free himself, Louie had chained himself, once again, to his tyrant. During the war, the Bird had been unwil ing to let go of Louie; after the war, Louie was unable to let go of the Bird.

——

One night in late 1948, Louie lay in bed with Cynthia beside him. He descended into a dream, and the Bird rose up over him. The belt unfurled, and Louie felt the buckle cracking into his head, pain like lightning over his temple. Around and around the belt whirled, lashing Louie’s skul . Louie raised his hands to the Bird’s throat, his hands clenching around it. Now Louie was on top of the Bird, and the two thrashed.

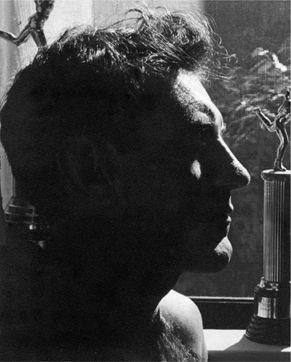

Louie, after the war. Frank Tinker

There was a scream, perhaps Louie’s, perhaps the Bird’s. Louie fought on, trying to crush the life out of the Bird. Then everything began to alter. Louie, on his knees with the Bird under him, looked down. The Bird’s shape shifted.

Louie was straddling Cynthia’s chest, his hands locked around her neck. Through her closing throat, she was screaming. Louie was strangling his pregnant wife.

He let go and leapt off Cynthia. She recoiled, gasping, crying out. He sat in the dark beside her, horrified, his nightclothes heavy with sweat. The sheets were twisted into ropes around him.

——

Little Cynthia Zamperini, nicknamed Cissy, was born two weeks after Christmas. Louie was so enraptured that he wouldn’t let anyone else hold her, and did al the diapering himself. But she couldn’t cleave him from alcoholism or his murderous obsession. In the sleepless stress of caring for a newborn, Louie and Cynthia fought constantly and furiously. When Cynthia’s mother came to help, she wept at the sight of the apartment. Louie drank without restraint.

One day Cynthia came home to find Louie gripping a squal ing Cissy in his hands, shaking her. With a shriek, she pul ed the baby away. Appal ed at himself, Louie went on bender after bender. Cynthia had had enough. She cal ed her father, and he sent her the money to go back to Miami Beach. She decided to file for divorce.

Cynthia packed her things, took the baby, and walked out. Louie was alone. Al he had left was his alcohol and his resentment, the emotion that, Jean Améry would write, “nails every one of us onto the cross of his ruined past.”

——

On the other side of the world, early one evening in the fading days of 1948, Shizuka Watanabe sat on the lower floor of a two-story restaurant in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district. Outside, the street was lively with shoppers and diners. Shizuka faced the door, watching the blur of faces drifting past.

It was there that she saw him. Just outside the door, gazing in at her amid the passersby, was her dead son.

Thirty-eight

A Beckoning Whistle

FOR SHIZUKA WATANABE, THE MOMENT WHEN SHE SAW HER son must have answered a desperate hope. Two years earlier, she’d been driven up a mountain to see a dead man who looked just like Mutsuhiro. Everyone, even her relatives, had believed it was he, and the newspapers had announced Mutsuhiro’s suicide. But Shizuka had felt a trace of doubt. Perhaps she’d registered the same sensation that Louise Zamperini had felt when Louie was missing, a maternal murmur that told her that her son was stil alive. She apparently said nothing of her doubts in public, but in secret, she clung to a promise that Mutsuhiro had made when he had last seen her, in Tokyo in the summer of ’46: On October 1, 1948, at seven P.M., he’d try to meet her at a restaurant in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo.

While she waited for that day, others began to question whether Mutsuhiro was real y dead. Someone looked up the serial number on his army sidearm and found that it was different from that of the gun found beside the body. Mutsuhiro could easily have used another weapon, but an examination of the body had also found some features that seemed different from those of the fugitive. The detectives couldn’t rule out Watanabe as the dead man, but they couldn’t confirm definitively that it was he. The search for him resumed, and the police descended again on the Watanabes.

Tailed almost everywhere she went, her mail searched, her friends and family interrogated, Shizuka endured intense scrutiny for two years. When October 1, 1948, came, she went to the restaurant, apparently eluding her pursuers. There was her son, a living ghost.

The sight of him brought as much fear as joy. She knew that in appearing in public, standing in ful view of crowds of people who had surely al heard of the manhunt for him, he was taking a huge risk. She spoke to him for only a few minutes, standing very close to him, trying to restrain the excitement in her voice. Mutsuhiro, his face grave, questioned her about the police’s tactics. He told her nothing about where he was living or what he was doing.

Concerned that they would attract attention, mother and son decided to part. Mutsuhiro said that he’d see her again in two years, then slipped out the door.

The police didn’t know of the meeting, and continued to stalk Shizuka and her children. Everyone who visited them was tailed and investigated. Each time Shizuka ran errands, detectives trailed behind her. After she left each business, they went in to question those who had dealt with her. Shizuka was frequently interrogated, but she answered questions about her son’s whereabouts by referring to the suicides on Mount Mitsumine.

More than a year passed. Shizuka heard nothing from her son, and the detectives found nothing. Everywhere there were rumors about his fate. In one, he had fled across the China Sea and disappeared in Manchuria. One had him shot by American GIs; another had him being struck and kil ed by a train after an American soldier tied him to the track. But the most persistent stories ended in his suicide, by gunshot, by hara-kiri in front of the emperor’s palace, by a leap into a volcano. For nearly everyone who had known him, there was only one plausible conclusion to draw from the failure of the massive search.

Whether Shizuka believed these rumors is unknown. But in his last meeting with her, Mutsuhiro had given her one very troubling clue: I wil meet you in two years, he had said, if I am alive .

——

In the second week of September 1949, an angular young man climbed down from a transcontinental train and stepped into Los Angeles. His remarkably tal blond hair fluttered on the summit of a remarkably tal head, which in turn topped a remarkably tal body. He had a direct gaze, a stern jawline, and a southern sway in his voice, the product of a childhood spent on a North Carolina dairy farm. His name was Bil y Graham.

At thirty-one, Graham was the youngest col ege president in America, manning the helm at Northwestern Schools, a smal Christian Bible school, liberal arts col ege, and seminary in Minneapolis. He was also the vice president of Youth for Christ International, an evangelical organization. He’d been crisscrossing the world for years, plugging his faith. The results had been mixed. His last campaign, in the Pennsylvania coal town of Altoona, had met with heckling, meager attendance, and a hol ering, deranged choir member who had had to be thrown out of his services, only to return repeatedly, like a fly to spil ed jel y. So much coal dust had bil owed through the town that Graham had left it with his eyes burning and bloodshot.

That September, in a vacant parking lot on the corner of Washington Boulevard and Hil Street in Los Angeles, Graham and his smal team threw up a 480-foot-long circus tent, set out sixty-five hundred folding chairs, poured down acres of sawdust, hammered together a stage the size of a fairly spacious backyard, and stood an enormous replica of an open Bible in front of it. They held a press conference to announce a three-week campaign to bring Los Angelenos to Christ. Not a single newspaper story fol owed.

At first, Graham preached to a half-empty tent. But his blunt, emphatic sermons got people talking. By October 16, the day on which he had intended to close the campaign, attendance was high and growing. Graham and his team decided to keep it going. Then newspaper magnate Wil iam Randolph Hearst reportedly issued a two-word order to his editors: “Puff Graham.” Overnight, Graham had adoring press coverage and ten thousand people packing into his tent every night. Organizers expanded the tent and piled in several thousand more chairs, but it was stil so overcrowded that hundreds of people had to stand in the street, straining to hear Graham over the traffic. Film moguls, seeing leading-man material, offered Graham a movie contract.

Graham burst out laughing and told them he wouldn’t do it for a mil ion bucks a month. In a city that wasn’t bashful about sinning, Graham had kicked off a religious revival.

Louie knew nothing of Graham. Four years after returning from the war, he was stil in the Hol ywood apartment, lost in alcohol and plans to murder the Bird. Cynthia had returned from Florida, but was staying only until she could arrange a divorce. The two lived on in grim coexistence, each one out of answers.

One day that October, Cynthia and Louie were walking down a hal way in their building when a new tenant and his girlfriend came out of an apartment.

The two couples began chatting, and it was at first a pleasant conversation. Then the man mentioned that an evangelist named Bil y Graham was preaching downtown. Louie turned abruptly and walked away.

Cynthia stayed in the hal , listening to the neighbor. When she returned to the apartment, she told Louie that she wanted him to take her to hear Graham speak. Louie refused.

Cynthia went alone. She came home alight. She found Louie and told him that she wasn’t going to divorce him. The news fil ed Louie with relief, but when Cynthia said that she’d experienced a religious awakening, he was appal ed.

Louie and Cynthia went to a dinner at Sylvia and Harvey’s house. In the kitchen after the meal, Cynthia spoke of her experience in Graham’s tent, and said that she wanted Louie to go listen to him. Louie soured and said he absolutely wouldn’t go. The argument continued through the evening and into the next day. Cynthia recruited the new neighbor, and together they badgered Louie. For several days, Louie kept refusing, and began trying to dodge his wife and the neighbor, until Graham left town. Then Graham’s run was extended, and Cynthia leavened her entreaties with a lie. Louie was fascinated with science, so she told him that Graham’s sermons discussed science at length. It was just enough incentive to tip the balance. Louie gave in.

——

Bil y Graham was wearing out. For many hours a day, seven days a week, he preached to vast throngs, and each sermon was a workout, delivered in a booming voice, punctuated with broad gestures of the hands, arms, and body. He got up as early as five, and he stayed in the tent late into the night, counseling troubled souls.