Uncivil Seasons (27 page)

Authors: Michael Malone

Cuddy apparently had eliminated Rowell as a suspect in Cloris’s killing on principles of schematic parallel structure. Despite his continual reminders to me that it is only in books that the same character commits all the murders, he was, in his investigations, strongly drawn to any congruity in modus operandi.

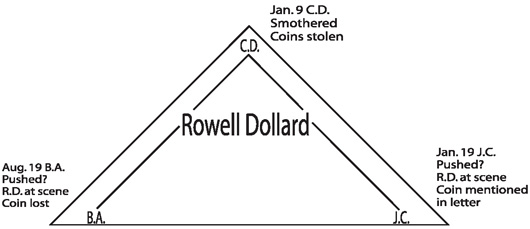

Here not only the obvious significance of Rowell's presence at the scene on the nights of both Bainton Aimes's and Joanna Cadmean's deaths, and the significance of their both falling (or getting pushed) were figured in; he also had inscribed in his geometric angles the fact that there had been discussion on both nights (Ames at the restaurant to Cary Bogue, Mrs. Cadmean to me by letter) of the 1839 Liberty quarter-eagle coin that was subsequently found in Cloris Dollard’s closet. He also seemed to think relevant the coincidence that both falls to death—separated by fifteen years—had taken place on the nineteenth of the month; the only fact in the cases that seemed to me to

be

just a coincidence.

I was studying his triangle when he loped back into his office and poked me pedagogically on the collarbone. “General Lee,” he said, “you are on the hill at Gettysburg, and if you will look around you, most of the coats you see are blue.”

I said, “Yours is gray.” He had on again his new three-piece herringbone suit.

“You are not supposed to be here. You are particularly not supposed to be here whopping your girlfriend’s husband in the jaw, who, by the way, just probably established Mrs. Dollard’s time of death for us at about 11:07, which is the time he said her phone clicked off, and which is jest a leetle too quick for the senator to have zipped in from Raleigh to kill her. However, I must say, I didn’t like old Lawry either. He had too many teeth, and every one of them was perfect. On the other hand, why wasn’t

he

hitting

you

? You’re the adulterer. ’Course, I’m not too up on the customs of the porticos-and-polo set.”

“Let’s drop it,” I said. “I’ve got to go. Rowell asked to see me this evening. I don’t know what for. And Ratcher Phelps wants to see me too, so I’m going there first. Want to come? I’ll explain in the car.”

Pulling straight up on one of his many cowlicks, he looked like a lanky puppet dangling from his own hand. “Sorry,” he sighed. “I’ve got an armed robbery, and an exhibitionist. And I have just returned from another little drive that was your idea, and that may be enough for me. But I had to testify in Raleigh anyhow, so…”

“You saw Burch Iredell? You got out to the vets’ hospital?”

“Yep, I slid on over through the slurp and saw your old coroner for you about the Ames drowning. Hiram Davies neglected to give you an update on Mr. Iredell, because time has bullied him around in the meanwhile, bad. I asked him if he could remember back fifteen years, he said he could remember back to the Flood. I said this was more like a lake. I asked him, ‘Mr. Iredell, you have any thoughts about whether back fifteen years ago Mr. Bainton Ames (since you were coroner back then and you signed the official papers) might have been, unofficially, murdered, and if so, sir, by whom?’ Well, Mr. Iredell said he certainly did have a notion Ames was murdered. Said the man sitting across from us had done it. Said this man shot Ames with the same rifle he’d used on JFK.”

“Come on,” I said. “Are you making this up?”

Cuddy flopped down in his chair and threw his long legs over the edge of the metal desk. He sighed, “I wouldn’t have the heart. You eat lunch? You tore out of the house so early to eat breakfast with Alice the future governor, I bet you’re hungry. You want that extra grinder? It’s meatball. I’m losing my appetite from falling in love.”

I ate the gooey sandwich, leaning my head over the wastebasket, while I told him why he’d better get back in touch with Cary Bogue. Then he told me more about his visit to the former Hillston coroner.

“Now, where the nurse wheeled Mr. Iredell out for us to have our little talk was the so-called recreation room of this veterans’ hospital, which speaking as a vet, all I can tell you is, it’s a funny way for a country to say, ‘We appreciate it, boys,’ because this particular snotgreen-painted place was truly ugly and had gotten all tumbledown—and was el-cheapo for openers. And I sure wouldn’t want to get recreated there—the reason being almost everybody I saw was about as scrawny and lost-looking as a plucked fowl escaped from Colonel Sanders. All this recreation room had was a little old black and white TV with furry channels, and some worn-out jigsaw puzzle boxes of the Grand Canyon, and these plastic checkers that the fellow that had allegedly murdered Mr. Ames was playing a game of solitaire with. Now, this alleged murdering fellow didn’t have any legs, had his pajamas folded over with safety pins, and he looked to me more the meditating type than your Mr. Iredell seemed to think he was, what with accusing him of killing Ames, JFK, the little children in Atlanta, plus being a North Korean spy who’s been slipping into Iredell’s room every night and stealing his desserts and planting electrodes in his head. Which the latter may be true, because your Mr. Burch Iredell, by the way, had a sort of sit-down disco movement to him, including his eyeballs, that didn’t seem to wear him out at all.” Still seated, Cuddy suddenly flailed himself about in palsied gyrations, his eyes spinning like Ping-Pong balls in a bingo hopper.

I said, “Will you quit kidding?” I had spent in the mountains many unending mornings in such a recreation room, among the checkers and the spasms, where each minute stretched like an orange pulling loose from the bough, too slowly to see it let go. I said, “Look, it’s nothing to kid about.”

Cuddy shook his head. “It ain’t my joke, General. It’s the Lord’s. If you think that’s kidding, you should have seen some of the fellows out there couldn’t make it down the hall to get to this recreation room. Let’s just leave it that your Mr. Iredell’s opinion is not going to be much use to Ken Moize in a court of law. Because law’s got no imagination.” Cuddy blew out another long sad sigh. “Humankind,” he said, “is breaking my heart.” Then he shuddered off the subject, and scooted his chair over to a paper package lying on one of his book crates. “Now, tell me, which one of these do you think? Which goes better with my suit?” He pulled out two ties. “I’m trying to improve my image so I can get Briggs junior to marry me. Women are always after you, and all I can figure is, it must be your clothes.”

“They don’t marry me.”

“Oh, they will when you mean it. Come on, which one?”

The first of the ties looked like a summer lightning storm, and the other one had orange squares on it. I said, “Are you seriously asking me?” He nodded morosely. I took off my own tie and handed it to him. “This one,” I said. “Trust me.”

“That’s what my ex—”

“I know, I know.”

So I went by myself and tieless through snow now crunchy as brown sugar to see Ratcher Phelps in East Hillston at the Melody Store. Up front a young woman was clerking, and back among his pianos, Mr. Phelps sat in his black suit and black patent leather shoes and sheer black nylon socks. He was playing a banjo and talking a song to himself, as solemn as a family lawyer at the reading of a will. He kept on with it as I walked toward him: “If you need a good man, Why not try me?…” His long spoon-curved nails plinked a last sharp chord as I finished the verse for him in a soft whistle, my ears going pink as I heard myself doing it. He said, “Hmmmm,” his moist doleful eyes quickly blearing over a look of wry interest. “You know that tune, Lieutenant?” he asked.

“Yes, sir. ‘Big Feeling Blues,’ isn’t it? I have it on a Ma Rainey record, with Papa Charlie Jackson playing banjo.”

“Hmmmm.” He placed the glittering instrument carefully on top of the spinet behind him and gave a slide of his hand to his hair. The hair was a flat black color that looked dyed and straightened; he combed it with a deep side-part. “You like the blues?” he asked me. I nodded. He nodded back. He said, “I have it in my remembrance that a piano,” he skipped his hand, a diamond ring twinkling, over the spinet’s keyboard, “that a piano is your particular favorite. Who do you like on blues piano?”

I told him, “I like Fletcher Henderson. Lovie Austin. Professor Longhair. I like this lady Billie Pierce a lot. I like mostly old blues.”

He nodded in a stately way and repeated his oleaginous “Hmmmm,” and then we rested with that.

“Well, Mr. Phelps,” I began, “on the phone this morning you mentioned wishing to discuss this matter of reciprocity with me. Here I am.” I sat down on a piano bench across from his.

Wetting his lips and pursing them a few times for practice, he said, “Young man, I have deliberated in my mind, and I have gone to my heart and asked it. And I believe that your,” he paused, searching among the spinets for a word, “your misimpression about my business, which is the business you see here before you, and not the jewelry business,

was

a misimpression.”

I smiled, nodding. “Mr. Phelps, I am here as a music lover. And I am here alone. And anything you may kindly choose to say will be held in the uttermost confidentiality. I give you my word.”

He accepted it with five slow nods. “Let us then,” he said, the voice warming, “let us then take a supposing. Suppose on that constitutional walk I believe I told you I have the habit of taking?”

“Yes?”

“Suppose those particular articles I believe you told me you were looking for, suppose they came to my notice, and the individual which they did not belong to also came to my notice? Now, in such a supposing as that, what would be interesting to know is if you people have any remuneration in mind for the recovery of those lost articles…throwing in that unnamed individual for no charge?”

I gave him a very serious frown. “Mr. Phelps, Mr. Phelps. I thought we had already settled on your remuneration—when we came to our agreement on the matter of your nephew Billy, and his upcoming trial. Here you are raising the rent.”

Like a minister of an old Ming dynasty, he stood up, small, portly, and sedate. “Billy,” he said, “is my sister’s baby. That poor widow grieves over her boy, and I in my heart at night in bed, I grieve over her, and a little extra re…muneration would go far to help ease her trials, and rent. That lost property is valuable property. According to you white people that lost it, now. I wouldn’t know. Worth more than all you see before you.”

I stood up too, and we studied each other. Meanwhile, at the front of the store, a fattish child with idolatrous eyes spluttered notes out of the brassy, bright trumpet the clerk had taken down for him; his mother watched, pleasure and distress both in her face.

Finally, I asked Ratcher Phelps if he had the stolen jewelry and coins with him. He said this was a music store. I asked him if he knew where the goods were, and who had them. He asked me to find out what the reward would be if he answered that question, and then ask it again. He offered me another of his suppositions: it would be astute of me to hypothesize that the more quickly I returned with an agreeable figure, the more likely I was to be present at an upcoming rendezvous between Mr. Phelps and the unnamed seller of the Dollard property. I was to suppose that Unnamed had contacted Phelps out of an urgent need for immediate cash.

I asked, “Are we talking about a Mr. Luster Hudson?”

Phelps rubbed his topaz cuff link, big as a cat’s eye, on the black sleeve of his other arm.

“Ron Willis?” I asked.

“Young man,” said Ratcher Phelps, “we are talking about Ma Rainey and Billie Pierce.” He picked up his banjo, cradling it across his dapper pouch. “And,” he added, leading me to the front of the store, “up here let me call to your attention a book of Fats Waller’s melodies that I am partial to, and I believe you would find them interesting to undertake.”

With a hand on his shoulder, I stopped him. “Mr. Phelps, now, let’s spell this out, all right? I get this money for you, and you’ve got to promise me I’m going to be there looking on when those coins are turned over to you.”

His perfectly specious smile rippled over the deep black jowls. “Oh, young friend,” he said. “Let’s just play the tune. Let’s not sing out all the words.”

I don’t like hospitals. My father liked the clarity of urgency there. I don’t like the sterile smell, the sealed windows, the sharp quality of light and life insisted on. When I was a child, University Hospital meant to me the big square building that wanted my father to be in it most of his time, and that would call him away loudly out of his sleep, insisting that he return. As this building was also the ogre-haunted, inexplicable maze into which, from time to time, elderly relatives of mine would walk, never to come out again, simply to vanish from my life, I was always terrified that my father, too, would be snapped up by whatever monster crouched hungry behind some turn of the endless halls. He, a surgeon, always joked that no doctor and no nurse of his acquaintance would be caught dead staying in University Hospital as a patient; they knew too much to risk it. “Good Christ, Peggy,” he’d say, “whatever happens, just keep me at home in bed and let me sniff chicken soup.” But, of course, the ambulance that sludged through snow to the foot of Catawba Drive where I sat in the smashed car, holding my father, blood from my mouth sliding onto his unconscious face, that ambulance rushed him straight to University Hospital, where they are supposed to know how to make the bad things stop happening. And after six months more, he was caught dying there; while west in the mountains, in a hospital of recreation rooms, I was caught alive.