Under a Dark Summer Sky (28 page)

Read Under a Dark Summer Sky Online

Authors: Vanessa Lafaye

Although I was born and raised in Florida, I was unaware of the events on which this book is based until I stumbled on them accidentally in 2010 while researching the idea for another book. The story then completely took over my imagination. As my research progressed, I began to realize that it was one of the most scandalous episodes of the periodânot just for Florida, but for the United States as a whole.

It was a desperate time for many in 1935. The nation was still on its knees from the effects of the Great Depression. The economic hardship and competition for jobs did nothing to ease the racial tensions going back as far as the Civil War. These were exacerbated by the return of thousands of black soldiers from the battlefields of World War I, who brought with them new ideas about equality of opportunity that terrified white Americans. Every aspect of daily life was segregated by the Jim Crow laws enacted in the 1880s. It was illegal for blacks and whites to marry or cohabit; all facilities, from hospitals to restaurants to prisons to libraries, were supposed to be “separate but equal”âbut of course only managed the former. It was illegal to promote equality of the races in written form. Even in death the doctrine reigned, as whites and blacks could not share the same burial grounds. These laws not only legalized discrimination for whole generations, but also legitimized violence against those who transgressed the laws. I was shocked to learn of Florida's status as “lynching capital of the South” in 1935, having always associated this with the “real” deep Southern states like Alabama and Mississippi. Lynchings were carried out for a variety of supposed crimes, including infringement of labor laws, but there was nothing more heinous than a crime of violence by a black man against a white woman, such as the one for which Henry is accused. At this time, white men ruled supreme, especially those with money. At the other extreme were poor black women like Missy, Selma, and Mama, with virtually no civil rights as we understand them today.

For the veterans, both white and black, life was extremely hard. Many had left jobs to fight for their country but came back to destitution. In 1922, Congress had approved a bonus for their service, due to be paid out in 1945. As the teeth of the Depression bit deeper, these veterans began to pressure Herbert Hoover's government to make an early payment. In 1932, up to 40,000 veterans and their families made camp outside the U.S. Capitol building while Congress debated the question of an early payment of the bonus. (One of the most interesting yet overlooked features of this camp was the complete integration of black and white veteransâfor the first time ever. It was not remarked upon by the press at the time and would not be repeated for many years.) The House of Representatives approved the motion, but it was overwhelmingly defeated in the Senate. Many of the veterans left the scene at this time, even further dejected and dispirited. Those 3,500 or so who stayed behind were perceived as both a threat and an embarrassment to the Hoover administration. Fearing that the police would lack the resources to deal with the veterans, Hoover authorized the army to disperse the crowds. George Patton, charged with commanding the cavalry, said later that it was “the most distasteful form of service.” The violence erupted into a national scandal that was a key factor in ensuring Franklin D. Roosevelt's victory in the next presidential election. The penniless, desperate veterans had helped bring down a governmentâbut had to wait until 1936 to get their bonus.

Roosevelt did not have long to enjoy his election victory. With the economy still in critical condition, and the specter of further unrest from the veterans, he was quick to set up public works projectsâboth to provide employment for the disgruntled soldiers and to rebuild areas devastated by the Depression.

It is not hard to see why this group of hopeless men, scarred by their experiences of war and defeated by their government, would have been attracted to a works project in the Keys. Many had been living rough for years. As I learned more of their story, I began to feel it was important to make more people aware of what happened to these men: that they were housed in appalling conditions and left to die, through a combination of apathy and incompetence, when a major hurricane struck.

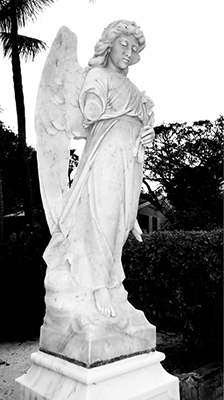

Equally, the residents of Islamorada, the town on which the fictional Heron Key is based, were unprepared, either for the veterans' arrival or for the hurricane's powers of destruction. It is easy to imagine the disruption caused by the hundreds of bedraggled, disturbed soldiers on a small, isolated community, which itself was struggling with economic hardship. The tragedy that befell the Conchs was no less shocking in its loss of life. With their long experience of hurricanes, they thought they were ready, but none of their preparations could withstand winds and waves of such magnitude. When the storm finally receded, the area of devastation resembled the photos taken at the epicenter of an atomic bomb: no buildings, no houses, no trees. Nothing left standing. Even the soil was stripped from the coral bedrock. A large stone angel, a grave marker from the seaside cemetery, was lifted and whisked 150 feet away by the wind. She still resides in the same cemetery, her broken arms never repaired, as a reminder of that night.

Although meteorological science was primitive by our standards, with none of the hurricane tracking systems we rely on today, the risks of storm season were well understood by all. Ernest Hemingway, who lived in Key West at the time, was one of the first on the scene after the storm and helped with the cleanup operation. His conclusion, published in the article “Who Murdered the Vets?” (

New Masses

, September 17, 1935), was clear:

Who sent nearly a thousand war veterans, many of them husky, hard-working, and simply out of luck, but many of them close to the border of pathological cases, to live in frame shacks on the Florida Keys in hurricane months? You could find them face up and face down in the mangroves. They hung on there, in shelter, until the rising water and wind carried them away. They didn't let go all at once, but only when they could hold on no longer⦠You found them high in the trees where the water had swept themâ¦and in the sun all of them were beginning to be too big for their blue jeans and jackets that they could never fill when they were on the bum and hungry⦠You're dead now, brother, but who left you there in the hurricane months in the Keys where a thousand men died before you in the hurricane months when they were building the road that's now washed out? Who left you there? And what's the punishment for manslaughter now?

In the investigation that followed, no one was ever prosecuted for what happened to the veterans, despite compelling evidence of official culpability. One of the great ironies is that the same scandal that brought Roosevelt to power almost cost him the presidency, such was the nation's outrage at the veterans' deaths. On September 12, 1935, the

Chicago Daily Tribune

wrote that putting the veterans in the Keys during hurricane season was:

â¦a piece of criminal folly committed by someone in Washington. The camps on the Florida Keys were established to avert another bonus march on Washington, with all the political embarrassments involved in such a demonstration of discontent⦠Naturally a site was selected as far from Washington as it conveniently could be while still providing free labor for a southern constituency which wanted public improvements at somebody else's expense.

People will say that such a thing could not happen today, but the residents of New Orleans might disagree. We have thousands of damaged soldiers making an uneasy reentry into civilian life, with a shockingly high suicide rate that is an indictment of their treatment by the military establishment and society as a whole.

None of these characters are based on real people. The real hurricane struck Islamorada and the other Keys on Labor Day, not the Fourth of July. There would have been a separate “colored” area of the beach a fair distance away, not right next to the beach reserved for the whites. Such is the license of fiction. Many of the events depicted did not happen, but some of them did, as told by the survivors. General Douglas MacArthur, given the job of breaking up the Bonus Army protest march in Washington, was worshipped as a hero by the very men he drove out with bayonets and gas. Some of the black residents were turned away from a storm shelter in town, which was then destroyed, forcing the white residents to join the blacks in empty boxcars for safety. The tragically late relief train was blown off the tracks by the storm before it could evacuate the veterans. Almost all of the veterans died, and so did many, many of the locals. People were found high up in the lime trees and as far as forty miles away, dropped there by the wind. Unlike Missy and Nathan, they did not survive for long.

Some who did survive have recorded their memories in a fascinating video to be found on the Keys History site at

www.keyshistory.org/shelf1935hurrpage15.html

, which also has photos of the memorial erected by the American Legion. The decapitated remains of Flagler's magnificent East Coast Railway, never rebuilt to this day, can still be seen in the turquoise waters off the Keys. They mark the place where, on Labor Day 1935, Nature demonstrated her prodigious power over us.