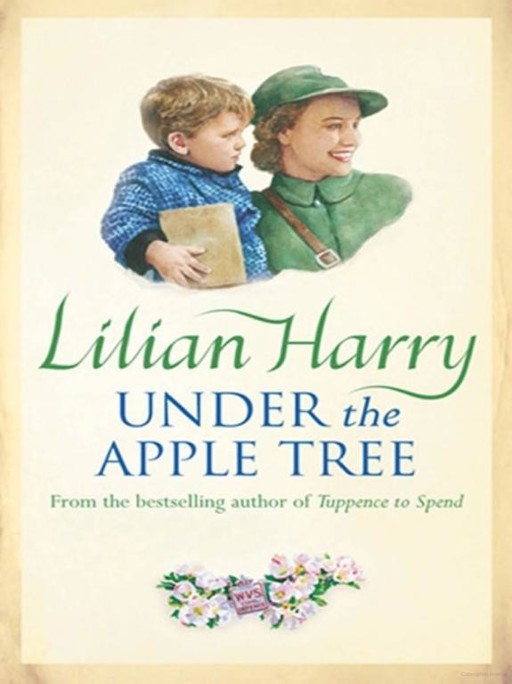

Under the Apple Tree

Portsmouth 1941, and the Luftwaffe unleashes

its full armoury in the first of three major blitzes.

Judy Taylor and her family are bombed out and

relocated to a small terraced house in April Grove.

Then, just when Judy thinks things can’t get any

worse, she hears the most devastating news:

her fiance has been killed.

Judy is encouraged to join the WVS with her recently

widowed Aunt Polly, and they are soon accompanying

evacuee children and running canteens, often in the

face of air raids, flying bombs and V2 rockets.

Gradually Judy and Polly begin to come to

terms with their grief — but neither of them

is prepared for a surprising future …

‘It’s all right,’ Polly said. She looked down at their hands. Hers, small and slim, was almost lost in his big hand. She saw that, like herself, he wore a plain gold wedding ring. That was unusual, she thought. Not many men did that. She drew in a shaky breath and

said, ‘I think I’m getting over it a bit now. I mean, so many things have happened and so many people have been killed. You just have to get on with life, don’t you?’

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘You do.’ There was a moment’s silence and then he tucked her hand into the crook of his arm and they walked on.

Polly took a deep breath, and then another. Mentioning Johnny

always brought an ache to her throat, but she could feel a comfort in the warmth of this big man, with her hand tucked so securely against his body. She had a sudden longing to be held close, to be hugged. No more than that - just to be hugged. To feel the

closeness of another human being. To feel the warmth of a living body close to hers.

Oh Johnny, she thought, where are you? What happened to

you? And did you think of me, during your last few moments? Did you know how much I loved you - and did it help at all? Or did

you forget everything and everyone in those last desperate efforts to stay alive?

The tears came to her eyes and, without knowing it, she

tightened her grip on Joe Turner’s arm. He glanced down at her

but said nothing, and if she had looked up at him then she would have seen that his eyes were wet too.

Lilian Harry grew up close to Portsmouth Harbour, where her

earliest memories are of nights spent in an air-raid shelter listening to the drone of enemy aircraft and the thunder of exploding

bombs. But her memories are also those of a warm family life

shared with two brothers and a sister in a tiny backstreet house where hard work, love and laughter went hand in hand. Lilian

Harry now lives on the edge of Dartmoor where she has two ginger cats to love and laugh at. She has a son and daughter and two

grandchildren and, as well as gardening, country dancing, amateur dramatics and church bellringing, she loves to walk on the moors and - whenever possible - to go skiing in the mountains of Europe.

She has written a number of books under other names, including

historical novels and contemporary romances. Visit her website at www.lilianharry .co.uk

By Lilian Harry

Goodbye Sweetheart

The Girls They Left Behind

Keep Smiling Through

Moonlight & Lovesongs

Love & Laughter

Wives & Sweethearts

Corner House Girls

Kiss the Girls Goodbye

PS I Love You

A Girl Called Thursday

Tuppence to Spend

A Promise to Keep

Under the Apple Tree

Dance Little Lady

Under the

Apple Tree

LILIAN HARRY

Copyright Š 2004 Lilian Harry

The right of Lilian Harry to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior

permission of the copyright owner.

All the characters in this book are fictitious, and any

resemblance to actual persons, living or dead,

is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

ISBN O 75285 929 3

Typeset by Deltatype Ltd, Birkenhead, Merseyside

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, St Ives pic

www.orionbooks.co.uk

For my dear grandson, Peter who took the time to show us over the hotel, taking Maurice back to the roof for the first time since the war ended; and to all those whose memories, research and chance remarks,

have helped me along the way.

Credit is theirs; errors are mine

The words of the song ‘Friend O’Mine’ were written by

Frederick Weatherley, who died in 1929. The song was one

which I remember my father singing to my mother at family

parties, and never fails to bring tears to my eyes.

The Taylor family already knew what they would find when

they crept out of their Anderson air-raid shelter on that

bitter morning of 11 January, 1941. Huddling together on

the two camp beds that Dick Taylor and his son Terry had

set up before Terry had gone away to sea, they had listened

in fear to the tumult outside and, when the ground beneath

them swelled and shook, when the very air seemed to

collapse in the roar of that almost unbelievable explosion,

when they knew that their own house must have been hit,

they had clutched each other in terror that they were about

to be blasted from their hiding-place.

The sheets of corrugated iron that formed a shelter over

the hole Dick and Terry had dug, had rattled and shaken

about them, and earth had crumbled through the cracks

between them. But they had held firm, and when the crash

of falling masonry and the smashing of glass had ceased,

Dick and Cissie and the others were still alive. Alive — but

not yet safe. It was another six hours before the All Clear

sounded and they dared to creep out and see, in the cold,

grey “light, what had been done to their home.

close beside her. Polly had been living with the Taylors ever since her husband Johnny had been lost at sea in the early

days of the war. At thirty-five she was twelve years younger

than Cissie, and the same number of years older than her

niece, thus she was more like a sister to twenty-two-year

old Judy and they had long ago dispensed with the title of

‘Aunt’. Now, as they crept up the garden path towards the

mound of broken beams, shattered glass and tossed bricks,

they reached out to each other and touched hands.

‘It’s awful,’ Judy said shakily. ‘Everything smashed to

bits, just like that. And what for? Why us? The man who

dropped that bomb doesn’t even know us. Why are they

doing it, Poll?’

‘It’s not just us,’ Polly said quietly. ‘You know that. Look

at what’s been happening in London and all those other

places. We’re all getting it. And I reckon Pompey got it as

bad as any last night. Look - you can still see the flames. It

looks as if the whole city’s on fire. There must be thousands

like us, bombed out of their homes. And thousands killed

too, I expect. At least we’re all alive.’ She bit her lip and

Judy knew that she must be thinking of Johnny. ‘Thank

God we were down in the shelter.’

Judy nodded. There had already been over thirty raids on

Portsmouth. The people had grown used to the eerie wail of

the siren and the frantic dash for shelter. They had heard

the thunder of the explosions and felt the earth quake as

craters were blasted into roads, and houses demolished.

They had emerged into devastated streets, picked their way

through the rubble and seen dead and injured lying like broken dolls where they had been flung. They knew what

had happened in London and Coventry. Yet they were still

not prepared for this terrible Blitz. Perhaps you never can

imagine the worst, she thought. Perhaps you always do

think it’ll never happen to you.

She had almost refused to go down to the shelter the

night before. She hated the confinement of the small space

half underground, with the corrugated iron curving low

over their heads. But the family’s insistence had forced her

to conquer her fears and now, seeing the ruin of her home,

she was thankful. If they’d let me stay indoors, she thought,

I’d be dead now, buried in all this rubble.

They paused and lifted their heads. A pall of dust and

filth hung about them like a fog, filling their mouths and

noses with its grit and stench. The sky was blackened by

smoke, shot through with searing flashes of red and orange

flame. Judy stared at it and felt her heart gripped by dread.

‘And how long are we going to stay alive?’ she burst out.

‘We were lucky not to get a direct hit on the shelter. They’ll

come again, Polly, they’ll keep on coming till we’re all dead.’

Tears were pouring down her cheeks. ‘Look at that. Our

house. Our home. Nothing left. All Dad’s books and Mum’s

sewing things, and our Terry’s gramophone and all our

records, and your Sylvie’s dolly that she left to keep you

company while she’s away, and - and …’ Sobbing, she ran

forward and began to tear at the rubble.

Polly gripped her arm tightly and drew her back.

‘Leave it, Judy. Cissie’s right - we won’t find anything

countries, and we haven’t got a chance.’

Polly stared at her. Her grey eyes, so like Judy’s and

Cissie’s too, hardened, and her mouth drew tight. She shook

Judy’s arm and her voice was low and fierce.

‘Don’t say that, Judy! Don’t ever say that. We’re not

going to let them win. We’re not going to give them the

chance. Remember Dunkirk! They didn’t beat us then and

they won’t now. They’ll never beat us. Never!’

Gradually, the people who had been bombed out of their

homes that night began to sort themselves out.

‘There was an ARP man round just now with a loud

hailer. He says we’ve all got to go to the church hall,’ Mrs

Green of number three told Cissie as the Taylors straggled

out of the back alley at the end of the street. Everyone was

out now, standing and staring in dumb stupefaction at the

destruction. Of the houses left standing, none had a single

window with glass in it, most had lost their chimneys and

several had their fronts torn away, so that the rooms inside

were exposed for all to see, like those of a dolls’ house. Mrs

Green’s bedroom wallpaper, that she’d been so proud of

when she’d had the room done up just before the war

started, was ripped and dirty, and there was a mass of laths

and plaster all over the bed. The bath was full of broken

slates and the lavatory hung half off the wall, with water

pouring out of the cistern above it. The floors had broken

away and there were boards, ceiling joists and all manner of

rubble piled in the downstairs rooms.

‘Look at that,’ she said bitterly. ‘We put all we had into

that house. Our hearts and souls. And look what they done to it. All smashed to bits.’ She turned away, her face

working. ‘We’ll never get it back to how it was, never.’

Cissie shook her head. ‘How many d’you think have been

bombed out like this? What’s it like in the rest of Pompey?’

‘Gawd knows. That ARP bloke says the whole city’s been

blasted away. All the big shops out Southsea way have gone

- Handley’s, Knight & Lee’s, all them - and the big Co-op

down Fratton has burned to a cinder, and the Landport

Drapery Bazaar, and Woolworth’s, and C&A.’

‘And the Guildhall too,’ someone else chimed in. ‘He said

the Guildhall’s still burning. So are the hospitals - the Eye

and Ear, and part of the Royal - and the Sailor’s Rest, and

the Hippodrome and—’

‘Blimey, ain’t there nothing left?’ Dick asked, his chest

wheezing.

Judy stepped forward quickly. ‘The Guildhall’s gone?’

She turned to her mother. ‘I ought to go there.’

‘But we don’t know where we’ll be. If we’ve got to go to

the church hall…’ Cissie stared at her, white-faced and

frightened. ‘What can you do anyway, if it’s all burned

down? You can’t go off now, Judy.’ Her voice rose. ‘And