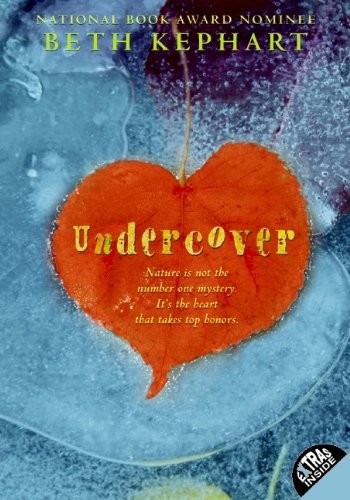

Undercover

Authors: Beth Kephart

Undercover

For my mother and father,

who gave me the gift of ice-skating.

And for my son, Jeremy,

the real writer.

—B.K.

ONCE I SAW A VIXEN and a dog fox dancing.

MY MOTHER AND MY SISTER could both be movie stars,…

I FOUND THE POND by following the stream that lies…

JILLY IS NOT SOMEONE who would stop and watch the…

I HAD TO THINK. I had to go right back…

THREE WEEKS AFTER I gave Theo the Lila note, I…

NOVEMBER’S DAYS are shorter than October’s. The sun hangs that…

IN DR. CHARMIN’S class I still could not guess if Rostand’s…

THAT AFTERNOON I went straight to the pond. I threw…

BEFORE JILLY became the world’s most accomplished couch potato, she…

IT SNOWED, and it snowed. I could hear the crystal…

THERE WAS NO SCHOOL the next day, and I was…

DR. CHARMIN HAD SAID that I was to report to her…

“IT’S UP TO YOU,” I was telling Theo, “to decide.”

WHEN A DAY STARTS like that one had, all you…

AFTER SCHOOL I was three of my eight blocks from…

I COULD NEVER TELL YOU all the names of every…

AT SCHOOL MOST PEOPLE kept their distance more than usual.

AN EPITAPH is what they write on tomb-stones. An epigraph…

I NEEDED THE SCORCH of the moon and the cold…

ONCE I HELD A BABY BIRD, but it was dying.

CHRISTMAS WAS ALWAYS my mother’s holiday. She started buying gifts…

I KNEW THINGS were different Christmas morning when I did…

I GOT A FEVER, then, and I couldn’t leave my…

THE FIRST FEW DAYS of January I stayed home from…

THERE’S A MIRROR in my parents’ room that runs floor…

YOU ARE BORN or you’re not born with a talent…

THAT AFTERNOON Dr. Charmin introduced the villanelle, another something French, she…

IT USED TO BE in winter that I dreamed of…

ONCE I SAW A PICTURE of Mom and Dad together…

THE NEXT MORNING Theo was at my locker with the…

I GOT TO THE POND as early after school as…

THE NEXT MORNING I asked Mom if she could clip…

THERE WERE DAYS after that when the only Theo I…

THE NEXT DAY was the thirteenth, a Friday. The sun…

THAT NIGHT Mom joined us downstairs for dinner. We had…

THERE WERE ONLY fifteen days between our soup and cheese…

ONCE DAD AND I went treasuring when I was nine…

AFTER CHRISTIAN DIES on the battlefield, Roxane retires to a…

ALL THROUGH the next several days I kept the poem…

THAT SATURDAY I rose before dawn, when the stars were…

THE PARKING LOT at the Border Road Rink was thick…

YOU EVER HAVE IT HAPPEN that a power so infinitely…

O

NCE I SAW A VIXEN and a dog fox dancing. It was on the other side of the cul-de-sac, past the Gunns’ place, through the trees, where the stream draws a wet line in spring. There was old snow on the ground that day, soft and slushy, and the trees were naked; I had my woolen mittens on. I was following the stream, and above and between the sound of the stream was the sound of birds, and also nested baby squirrels. The foxes, when I found them, were down by the catacombs, doing a slow-dance shuffle. Standing upright, I swear, palm to palm, with black socks on, red coats.

At school I didn’t tell Margie about the fox dance, or David, or Karl. I didn’t even tell Mr. Sheepals, in science, because it was what he’d call a non sequitur. My fox-dance story was an animal-kingdom story, and this was two years ago, second semester, eighth grade, when we were stuck on photosynthesis.

I have a sister, but she reads fashion magazines all day. My mother doesn’t care for the woods. I kept my fox-dance story to myself, and I won’t share it with others even now. It is my secret.

It’s the other stuff I give away—the way I read the sky, the way I watch the sun, the forty-two flavors of breeze. It’s everything people don’t look for until it’s too late, until they need a metaphor or simile to help promote their love. They don’t have to come to me, but they almost always do. They know I’ve got it covered.

Dear Sandy,

I’ll write, pretending I’m Jon.

I came to the track meet to see you run, and it was like watching the lead bird in a migrating V. You were something else. Again.

Then I fold the paper and I slip in a

feather from my Stash O’ Nature box. The next day Jon will rewrite it all in his own way and sail the thing through the vents of Sandy’s locker, and a week later, I’ll see them—Sandy and Jon, so all-in-love together—going down the hall. He’ll keep his eyes down, as conspirators do. “Hey,” I’ll say. “Hey,” he’ll mumble.

It’s interesting to me, what others cannot see. For example: The precursors of leaves on trees, which can be seen only just in front of dusk, in March, when the setting sun turns the branches pink or some primary shade of green. Then there’s the neon glow of the eyes on bees, and also the way a gerbera daisy starts out thinking it’s yellow before it turns pink. Nature, you see, has a mind of her own. She’s mysterious, and mystery is romantic.

Dear Lori,

I write.

Last night I left my window open and a firefly flew through. So much light and all I could think of was you. Love Matt.

M

Y MOTHER AND MY SISTER could both be movie stars, and this is why: They are the same. They have corn-silk-color hair that dries slippery smooth and creamy, flawless skin. Their eyes are an interesting green. As people, they don’t muss. My sister has had the same pair of white jeans for two months now, and they still look like new. My mother’s pleated skirts are crisp, as if ironed with a ruler’s edge.

My dad’s so good at what he does that he’s needed all over the world. In London, sometimes, and in Paris and Rome, or in Chicago, New York,

and Boston. He’ll take the morning’s first plane, and a week or two later he’ll come back home in the dark. We eat canned spaghetti on the nights Dad is gone. Mom talks on the phone with her green skin mask on, or studies her catalogs of seeds. Jilly lies stretched from head to toe on the family-room couch, taking note of skirt lengths and accessories.

My dad has put his lifetime of looking into a company that he calls Point of View. The logo is cool—an eye with a map drawn into it—and his business, he says, concerns perspective. Finding it, sharing it, applying it, leveraging it.

Leveraging

, by the way, is a word for the future.

I got my dad’s curly auburn hair and altogether sensible-looking eyes. I got his pinprick freckles. And believe it or not, I got his double earlobe—one earlobe directly beside the other, like a lower case w—on the right side. It is for this reason that I do not wear my hair pulled back. Or bother with earrings. Honestly. I’ve got a couple of pairs of trousers and a couple of pairs of Keds and sweatshirts with

hoods, for bad weather. Woolen mittens and turtlenecks for the snow-is-coming season. T-shirts and two white blouses for the sticky days of summer.

Dad likes to say, about both of us, that we’re undercover operatives who see the world better than the world sees us, and this, I swear, has its benefits. For example: I can study Sammy Bolten’s nose all through lunch, and he’ll never, ever notice. Draw it in profile, if I want; write a caption under my drawing: Mount Pocono. Also I know just by looking when someone’s wavering with love or dreary with longing or about to turn and flee. Point of fact: It takes nothing to see.

I

FOUND THE POND by following the stream that lies in the woods past the Gunns’ place. It was a day in early October, and the leaves of the trees were glorified with highlights of henna and gold. I’d gone to the woods to test out my theory that acorns in autumn have smells, and also to work on a little something for Karl, who had a big new thing for Sue.

You’re the pink quartz in the sunlight, all sparkly and alive

, I conjured.

You’re the feather that the bluebird leaves behind

. Those were good, but they weren’t up to my standards. I still had some conjuring to do.

The squirrels were hysterical in the trees that day, hurtling off limbs like cannonballs. Above the squirrel circus was a big-winged hawk that rode a thermal, then flapped its wings to follow the stream. After a while I started following the hawk. I took off my shoes, and I went running through autumn air that was so acorn ripe that it crunched.

I didn’t see the pond until I’d gone down a slight hill and turned left between more trees, until I had passed between blue spruce, oak, and maple and steered deep toward the old mansions that had vanished over time—fallen down, been bulldozed down, been lost but for their ghosts. Everything cleared, and there was this pond and around the pond was this garden that had grown up and been abandoned—some end-of-the-season hydrangea, some wood anemone, some weedy trees and other stuff that was, as my dad says, long past its prime. The pond was round and still and murky green, and beneath the surface things were swimming that I couldn’t see, while above the pond, like a hole cut

out of cloth, there were no trees, just sky and hawk. You could get out and over the pond by walking an old dock, and right near where the dock planking began was a shack, a sort of lean-to thing with a folded roof and lockless door.

For a while I just stood there staring at that pond. I parted some weedy trees to get a better look. I walked around to where the dock began and went out and sat and stared. That’s when I saw the girl beneath the water’s surface—the white sculpted girl that someone must have carried out and anchored in. She had a smile on her face, this marble girl, like she knew some things that I never would. She had a marble book upon her sunken marble lap; her hair was algaed green; her eyes were blank. More than anything else, she was so entirely, so admirably calm.

The point is: The pond had belonged to someone once. It had been dug out or built up, or something. It had been edged and gardened and statue blessed, and it had been furnished with its own

splintery dock—old planks of wood that had been hammered together for standing on or fishing from. There was rubbish about, of the most interesting sort—Hershey bar wrappers, smashed glass, wound-up balls of plastic twine, an old and rusty fishing pole, a moldering paperback. You don’t have to discover something first to be an undercover operative. You just have to know what to do with your find.

I sat on the dock and I studied the girl; I looked to the hole in the trees that was the sky and watched the floating, floating, floating of the hawk. I stretched out my arms and imagined the sovereignty of so much soaring. I thought of Dad in London, missing the best part of October. Track the changes and get back to me, he’d said before he left, and now here I was with all October in my reach—every color, smell, and sound. I wanted to take it all home and put it inside my box. I wanted to send it to Dad.

Here, for the record, is a list of things I’ve

managed to stow in my Stash O’ Nature box: The little wave-tossed shells I’ve found along the shore when the sea was pushed way back, and also sea-glass chips, which make stained-glass light when you hold them to the sun. All variety of rocks, pebbles, and stones, including mica so fine that I have cut it with a knife—peeled it, like it was fruit or something. The shed skin of a local snake, though that has mostly turned to dust. The dried husk of a lotus flower that sounds like maracas when you shake it. Seeds and long seedpods. Pinecones and burrs. An empty nest that had been stormed out of a tree. Tree leaves, crisped. The very tip of a tail that a squirrel left behind. Bird feathers. Wishbones that I never cracked. The faces of flowers I picked in time to press between the pages of fat books. Beetle bodies and ladybugs that were all done with living. Three green cicada shells. A pile of acorns, each with its cap. Some Polaroids of passing clouds. A vacant robin’s egg.

My Stash O’ Nature box is not a shoe-size box.

It’s the old hatbox I found in the attic. It’s got designated spaces for each species of thing, and the empty nest sits right dab in the middle, crowned by the vacated egg. When I pull the box out from underneath my bed, I’m the utmost in careful. I never yank. I never shake, and in that way the goods stay safe. Nature is a force, but it is delicate, too. You have to take care of what you find.

Dear Sue, your smile is as bright as the bleached shells at the seashore.

Lame. I can do better.

Dear Sue, I’m as empty as a cracked egg except when you’re with me.

No. No one would believe it.

Dear Sue, You are as perfect as the mathematics in a pinecone.

Not my best, but better.

I felt sorry for Dad being busy in London, when all of October was right where I was and where a pond, at least for the day, had been left entirely to me. He said he’d gone and had a chat with Big Ben and had taken a meander through the Tower of London, but that was nothing, and he’d said so, when compared to what was happening with the

sugar maple trees. He couldn’t remember what order the colors came in, he said, and he wanted me to tell him. He couldn’t remember if tulip tree leaves skipped right over yellow in favor of red.

Dear Dad,

I’d write when I got home.

I wish you were here with me. The trees are staging the best-ever show. The orange is closer to pink in places, and the red can go straight off to purple, and some of the leaves stay the brightest of green so you can’t forget how they started. This year you’d like the yellow leaves best. They’re pure as gold. I don’t think any of the birds are going south. They want to stay with the action.