Understanding Air France 447 (14 page)

The flight directors provide guidance from shortly after takeoff to landing. They can provide guidance for all normal operations and even low altitude wind shear recovery, but not for traffic or terrain avoidance or stall recovery.

The flight directors are extremely reliable. Unfortunately, it is easy to fall into the trap of following the flight directors so intently that that actual instrument indications are ignored.

They will automatically disappear when the data upon which their commands are based is not agreed upon by two out of three sources, or when abnormal pitch or bank angles are reached. They will change modes or disappear if the speed becomes excessively high or low, with the new mode annunciated on the FMA. If they reengage after disappearing they will return in the vertical speed/heading mode at the vertical speed and heading that exists at the time. However, they do not automatically reengage in all situations.

In the case of Air France 447, the flight directors disappeared when the airspeed sources no longer agreed with each other and the autopilot disconnected. They reappeared several times during the subsequent climb, but they would not have been providing appropriate guidance to recover back to level flight. What is not known is if the pilots attempted to follow them.

Flight Path Vector

The A330 has an indication known as the Flight Path Vector (FPV). It is an optional display that can be used at any time. The flight path vector shows the actual flight path of the airplane both vertically and horizontally, independent of the pitch attitude. The FPV is derived from a combination of inertial data and altitude data. The values are derived from the barometric altimeter data, even if that is erroneous.

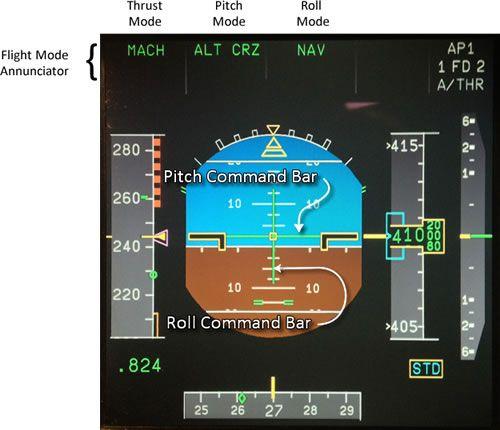

In the photo below the FPV is the green symbol on the horizon line. Notice that the airplane’s pitch attitude is actually about 9.5° up, but the FPV indicates that the flight path of the airplane is on the horizon, or level flight. If the airplane were descending, the FPV would be below the horizon an amount that corresponded with the descent angle.

If a crosswind exists, the FPV is displaced to either side of center to illustrate the actual direction of movement, despite the heading. The angle between the center of the display and the FPV represents the drift angle.

The crew of AF447 did not display the FPV during this flight. But an ACARS maintenance message was sent when the symbol was not available due a loss of data (calibrated airspeed below 60 knots), so I mention it here. The first interim report of the accident incorrectly stated that the error message indicated that the FPV was selected and unavailable. It was later corrected to clarify that the FPV did not need to be selected to generate the error message.

The display of the FPV may have been useful in maintaining level flight shortly after the autopilot disconnected. It may have also been useful to confirm that the airplane was in fact descending during the time when they appear to have been seriously doubting their altimeter indications.

When the FPV is displayed and the flight directors are on, the flight directors are presented as Flight Path Directors, where the pilots flies the FPV symbol to match the flight path director commands. Like the cross-bar flight directors, they provide no stall recovery guidance.

Once the airplane started to descend, the FPV would have been well below the horizon line, potentially further leading the pilot to pull back to correct the flight path. It would have eventually gone off the bottom of the scale altogether.

It is hard to say that the attempted use of the flight path vector could have made the situation worse, for the final outcome could not have been much worse than it already was. However, it may have aided the pilot flying in maintaining altitude early on if he did not know what pitch attitude to fly to maintain level flight once the autopilot, flight director, and airspeed were unavailable.

ECAM

System displays, alerts, and corrective actions are displayed on the ECAM (Electronic Centralized Aircraft Monitor (pronounced ē-cam). The ECAM consists of the two center screens on the forward instrument panel.

The upper screen or Engine/Warning Display (E/WD) displays the primary engine instruments, slat/flap positions, total fuel, and warning, caution, and advisory messages.

The lower screen displays the status of the various aircraft systems and takes the place of numerous dials and gauges in earlier generation aircraft. It also displays a STATUS page where a summary of inoperative components, preparations for landing, and other in-flight reminders are displayed.

When there is a system malfunction, the title of the malfunction is displayed along with a check-list of actions to stabilize or correct the situation. Crews use the messages and checklists displayed on the ECAM to address each one in an orderly manner. Messages are prioritized into warnings, cautions, and advisory messages, with the most important messages, the warnings always displayed first.

Each level of message, and some specific faults, also have an associated aural annunciation. An autopilot disconnect invokes a repeating “cavalry charge.” Other warnings sound a continuous repetitive chime (ding ding ding...), cautions a single chime (ding), and advisories have no sound.

The stall warning consists of a cricket sound and the words “STALL STALL” spoken by a synthetic voice. The red master warning light in front of each pilot is also illuminated.

A “C-chord” tone sounds in association with altitude. It is intended as an altitude awareness reminder. It sounds for 1.5 seconds when approaching a selected altitude if the autopilot is off, and sounds continuously when deviating more than 200 feet from the selected altitude. The continuous C-chord can be silenced by pushing the Master Warning light/switch on the forward glare-shield. This C-chord is an indication of an unusual situation (deviation from the assigned altitude), and it is not normal for it to sound, or to cancel it. On AF447, the C-chord first sounded within eight seconds of the autopilot disconnecting and remained on for almost the entire rest of the flight. It was only silent as they approached and descended through their original altitude of FL350 and when it was overridden by a higher priority audio alert such as the stall warning.

When a malfunction occurs, the acting pilot in command should assign duties (e.g., “You fly the airplane and take the radios, I’ll work the ECAM.”) Crews are trained and expected to handle each message in order starting at the top warning message and complete the associated steps in a methodical manner.

Some messages will clear themselves when the condition no longer applies or the step is completed, but not all. The ECAM system also includes a CLEAR key on the control panel that allows the pilot to clear messages so that additional messages can be read on the limited screen space, or to progress through the ECAM procedure.

Once the messages and associated checklists have been completed or cleared, the ECAM system will display the pages individual aircraft systems that have been affected by the non-normal conditions. For example, if a generator failed, after the generator fail message and the steps to attempt to reset or turn off the generator, the electrical system schematic will be displayed showing the failed generator and the electrical system’s reconfiguration. The clear key allows movement to the next affected system.

After the affected systems are displayed, the STATUS page is displayed. The status page shows a list of inoperative items, reminders, and additional steps in preparation for landing.

Some malfunctions have memory items because action is required right away and the malfunction may not be automatically detected and displayed on the ECAM. In cases where the ECAM does not, or cannot, detect the anomaly, crews should call for the appropriate procedure from the paper version in the Quick Reference Handbook (QRH). This is the case in instance of unreliable airspeed. There was no ECAM message for loss of airspeed. A memory item and paper check-list procedure applied.

Crews are not expected or trained to make up procedures and actions. However, a level of systems knowledge is expected that would allow them to understand the procedure steps and make appropriate decisions.

In any case, maintaining aircraft control is always the first order of business. In the AF447 accident it is clear that the crew failed to maintain control of the airplane as the first priority, suffered a loss of ECAM discipline, and made a venture into making up corrective actions.

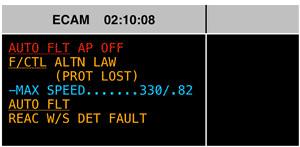

Illustrated below is the initial ECAM indication that appeared with about 5 seconds after the autopilot disconnected. Each message starts with the affected system, the associated malfunction, and then corrective actions, if available.

The first line in red is a warning level annunciation for the autopilot disconnection. The underlined “AUTO FLT” indicates the affected system is the auto-flight system. AP OFF indicates that that autopilot is now off by other than pilot selection. There are no corrective actions associated with this message - the crew must now hand fly the airplane.

The system does not necessarily make the cause of a failure clear. When the internal crosschecks of the airspeed parameters found a disagreement and caused the auto-flight systems to shut off, it did not annunciate that there was an airspeed discrepancy. It only altered the pilots that the auto-flight systems had been turned off. One of the recommendations of the accident report is that when specific monitoring is triggered, the crew be alerted to facilitate comprehension of the situation. Essentially, “airspeed discrepancy: autopilot is off” instead of the current system which amounts to, “autopilot is off, see if you can figure out why.”

The next message was a caution level message relating to the flight control system, indicating that the airplane’s active flight control law had changed to Alternate Law, followed by a reminder that the protections provided by Normal Law are now lost, and that the crew should not exceed 330 knots or Mach .82. This is a slight reduction from the normal maximum speed of 330 kts/Mach .86 due to the loss of the protection. The MAX SPEED step is always displayed with the Alternate Law annunciation and should have been familiar to the crew from training. The minimum speed remains unchanged. The report speculates that because only a maximum speed is shown and not a minimum speed, that “this could lead crews to suppose that the main risk is over-speed. In the absence of any reliable speed indication, this might lead to a protective nose-up input that is more or less instinctive.

25

” I do not think this is the case, as the maximum speeds were not read out loud by First Officer Robert when he was performing the ECAM steps.