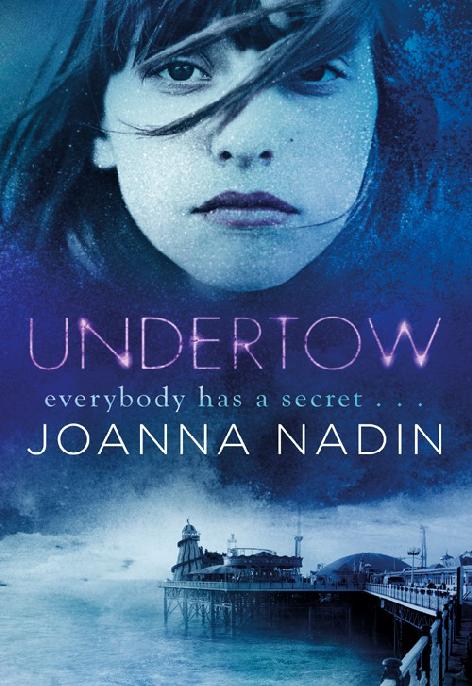

Undertow

Authors: Joanna Nadin

Contents

For Helen Nadin

.

With thanks to Al Greenall for painting in the gaps

.

SECRETS

WE ALL

have secrets.

Like not liking your best friend that much. But you don’t dare tell her because she holds reputations in her hand like eggshell, and if she moves just a finger you’re broken, over.

Like keeping your mouth closed when you swig your Bacardi Breezer so she thinks you’re as drunk as she is. But when she’s not looking you pour half the bottle behind the wall.

The usual stuff.

Even my little brother has secrets. Like he thinks no one knows it was him who drew the solar system on the kitchen ceiling. I knew. But I said nothing. Because those kinds of secrets don’t matter. Not really. They’re fleeting, like insects, mayflies. Alive for just a day.

But some secrets aren’t mayflies. They’re monstrous things: skeletons locked in cupboards; notes slipped through the cracks in floorboards and between the pages of books. And, though the ink fades and the paper foxes, the words are still there. Waiting to be found. Or to find us.

If I had known who he was – who

I

was – would it have changed anything? Or would I still have felt that weight on my chest, pushing the air out of my lungs so that, when I saw him, even that first time, I struggled to catch my breath? Would I still have lost hours, nights, thinking about his lips, his slow, lazy smile? And would I still have fallen in love, if I had known?

Maybe. Maybe not. But that’s it: I didn’t know. Because it was Mum’s secret. Het’s secret. And, like all skeletons, it came out of the closet. And it found me.

BILLIE

THE KEY

arrived three days after Luka left. Mum said it was serendipity. I didn’t believe in that kind of stuff, just thought it was a nice word, like

egg

, or

pink

. Back then, anyway. But maybe it

was

serendipity, fate, whatever, because Mum was already kind of losing it. Not big-men-in-white-coats style. Not that time. Just the little things. Like I found her in the kitchen with one of his T-shirts, just standing there, sniffing it. And when I called her Mother as a joke she slammed a glass of Coke down so hard it shattered; shards of transparency scattering across the floor, a slop of soda soaking into a dishcloth.

It wasn’t like he was gone for ever – Luka, I mean. He was in Germany with some band for three months – guitarist for a kid half his age and twice his talent, he said. But that wasn’t true and he knew it. Luka was good. Which was why he was always getting gigs. Always leaving. He always came back, though. But that wasn’t enough for Mum. She said she was tired of it, tired of waiting. She said if he went this time then we might not be here when he knocked on the door come Easter. Luka laughed and said he wouldn’t knock; he had a key. He kissed the top of her head and wiped her angry tears with his string-hardened fingers. But she pushed him away and said this time she meant it.

None of us believed her. I mean, he’s Finn’s dad. She couldn’t just disappear, hide. But then the envelope arrived and everything changed.

Mum is out with Finn getting milk and bread and fresh air, or something like it. I say it’s too cold, that I don’t like fresh air, and I stay in the flat upstairs with the curtains closed and an old Mickey Mouse T-shirt on, and wrap myself up in my duvet and the white-smile world of Saturday-morning telly.

And I’m lying on the sofa watching Tom pot Jerry like he’s a snooker ball when I hear the clatter of the letterbox in the shared hallway below, and the post hitting the piles of pizza delivery leaflets, sending them fluttering further across the floor. And I can’t remember why, but I get up. Maybe I think it’s a postcard from my best friend Cass in the Dominican Republic with her dad and the Stepmonster, getting a tan and another hickey from a boy she’ll claim is the love of her life then won’t remember when she gets back.

But, when I see it, I know it isn’t from Cass. The postmark isn’t foreign, but it isn’t from round here either. It’s a Jiffy envelope, the kind you put fragile stuff in, important stuff; not one of Cass’s say-nothing notes, with hearts dotting her

i

s and

SWALK

on the back. And the writing isn’t Biro or pink gel pen; it’s black ink, with loops in the

l

s so that “Billie” looks alive. But the name is only half me. Because then the loops spell out “Trevelyan”, which is Mum’s old surname, before she changed it – changed us – to “Paradise”, a word Mum picked up from a sign above a shop door on Portobello. Kept it the way you keep a glass marble. Because she liked the way it felt in her mouth. Because she thought a name could make it happen, make it real.

I feel this surge of fear inside me. No, not fear exactly, thrill. The kind you get on a rollercoaster. Or when someone double-dares you to down a shot. Bad and good all wrapped up in one sickening whirl. And suddenly I’m small and scared, standing in my T-shirt and socks on the bare concrete, and I have to look around to check if anyone has seen me, if Mrs Hooton from Flat B is coming out in her slippers and threadbare dressing-gown to catch me with this— What? This thing in my hand. But I’m alone, and I shiver, the January air an icy hiss through the gaps around the door, stippling my thighs and arms with goosepimples. And I run back up the stairs and slam the door and pull the duvet around me again, still holding the envelope, hot in my hand like Frodo’s ring.

I think even then I knew it. That it wasn’t just a package. It was a talisman, a magic amulet to change my world.

I duck my head under the cover and roll onto my side, the light from the telly shining through the faded polyester flowers, so that I can open the envelope and wait for the power to seep out and transform my life.

And it almost does.

It’s a key. Not like ours. Not a shiny Chubb that locks out Mrs Hooton and the rest of the world. Locks us in. But the old kind. Heavy, blackened iron. The kind you get in fairy tales that opens up a haunted mansion in the woods, or a box of cursed treasure, or the Ark of the Covenant. And when I read the letter, with it pressing its cold metallic print into my palm, it feels electric. Because it

is

a fairy tale. Only it’s real. And it’s about me.

The story is simple, short. Typed in sharp Times New Roman on a single page. A woman has died. Eleanor Trevelyan. My grandmother. She has died and left me a house. Cliff House. In Seaton. In Cornwall.

I have inherited a house. The one Mum grew up in, and left sixteen years ago, when I was already inside her. Because I was already inside her.

Seaton. Sea Town. I sound the words out silently in my head. Picturing this strange place. This palace. And I feel that feeling again, that thrill. Because I know I should be pale and grieving for this lost dead woman. But the thing is: I have never met her. I kind of knew she existed. I mean, obviously my mum had to have a mother, and a father, though he’s long gone. She had a brother, too: Will. But he died. And I came. And Mum left and now she won’t talk about it.

So instead of crying, I laugh. Because it’s funny. It’s fairytale funny. Because I live in this two-and-a-bit-bedroom flat in Peckham with no carpet and a boiler that only works when it feels like it, and all along I have a house, a castle by the sea. I’m not the Little Match Girl, I’m Cinderella.

But then I hear the front door bang against the wall and Finn’s voice one long stream of Gogo’s and Jedis and “Did you see that?”s, and I remember who I am. I’m not Cinderella. Or Sleeping Beauty. I’m Billie. And Mum’s mother has died and she doesn’t even know, and I’m scared to tell her because every time I’ve mentioned her before, just casual, she has ignored me or yelled at me, or, worse, taken it out silently on herself. So I stuff the key and the letter back in the envelope and push them down the back of the sofa cushion. And they stay there for three whole days.

I thought about not telling Mum at all. I mean, I’m sixteen. I could just go and live there on my own. Live this incredible enchanted life in my castle by the sea. That’s what Cass said anyway. Or, better, I could sell it and buy somewhere up West. So we could go to Chinawhite’s instead of Chicago’s. But as she sat on the end of my bed, in her St Tropez tan, I knew every nod, every “yeah” was a lie.

I knew I’d tell in the end. Had to. Because my mum’s not like Cass’s, who doesn’t know Cass lost her virginity when she was thirteen. That it was to Leon Drakes and she wasn’t in love or anything like it. That she got pregnant and paid for an abortion with the money her dad sends her every month. The money she still spends on dope and drink and the slots at Magic City.

And even the stuff Cass’s mum does know she doesn’t really register. Because if she did, she wouldn’t let Cass do half of what she does.

But my mum’s different. My mum you tell stuff to. And this was big stuff. Family stuff. And the longer I left it, the worse it got. Because the key was like the tell-tale heart in that story we did for GCSE. This guy buries the heart of a murdered man under the floorboards, only he’s sure he can still hear it beating, this

thump thump thump

, and it slowly drives him mad.

And maybe it’s just my own heart, but I swear I can hear that key beating its presence, pulsing it out like heat. Like a heart. I look at Finn and Mum to see if they can hear it too. And even though Finn just carries on laughing at the cartoons and Mum flicks another page in a magazine, I know it is only a matter of time.

By Tuesday I can’t stand it any longer. I’ll be back at school tomorrow and I don’t want to leave Mum alone in the house with it. Don’t know what she’ll do if she finds it. As it is, I hide the big knife in the kitchen. Just in case.

I don’t say anything, just hand the envelope to her at breakfast, with this look on my face like I’m giving her my school report and there’s not even a C on it, let alone a B. I feel Finn yank my sleeve, hear him demand to know what it is, but I shrug him off because I’m watching Mum, hidden under her shroud of dirty blonde, her knees inside the black mohair of one of Luka’s sweaters, bare feet poking out. And I wait.

When she got a letter telling her that her father had died, she said nothing. Just shrugged and dropped it in the bin and went back to buttering toast. But this is different, I think. This is her mother. She was inside her once. Part of her. She has to lose it.

But she doesn’t, just stretches her legs to the floor and turns her head to me. And as she pushes her hair behind one ear, I see she is smiling.

“I should have told you before,” I say. “I mean, I meant to. It’s just— I didn’t know what you would—”

“It’s fine,” she interrupts. “Really.”