Unknown

Authors: Unknown

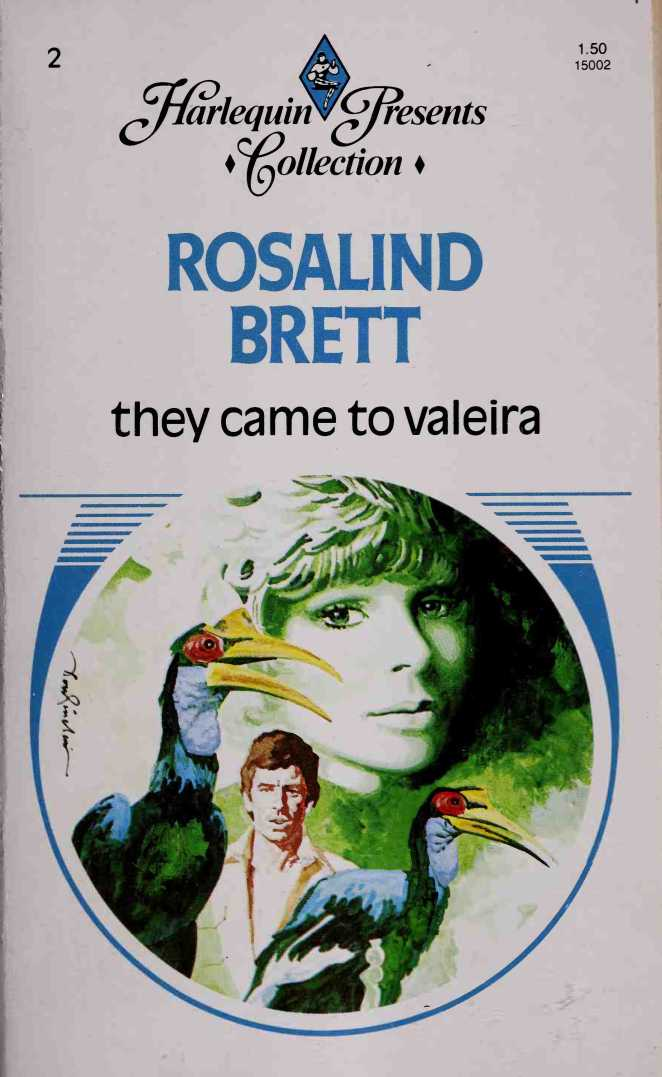

THEY CAME TO VALEIRA

Rosalind Brett

"You can't go on living among men."

Discovering Philippa Crane on Valeira made Julian Caswell angry Not only was he concerned for her welfare, but as new manager of the plantation he'd hoped for solitude and complete relief from women. So he ordered her to leave.

But Philippa was equally determined to stay. She won the first round against Julian's efforts to oust her, then wondered if it was worth it.

For how could she stay on Valeira now that she'd foolishly fallen in love with the bitter, inflexible Julian?

"Look here, Phil. This has to end. "

Julian leaned across the table as he continued, 'I'll take you to Lagos and put you on a liner, and you can leave the dissolution of that bogus ceremony in my hands."

"It is in your hands!" she cried furiously. "Go ahead with It, but don’t expect to ship me around like a sack of meal. I'm sick of your insensitiveness—l can do without your protection—"

"Stop it, will you? " he said savagely. "The minute we get together sparks fly—your nerves must be cracking. ”

"My nerves were sound enough till you got to working on them," Phil choked. "Go for your holiday, Julian. Find a woman in Lagos and laugh with her about the kid down in Goanda who fancies herself in love with you...

She got up quickly and ran to the bedroom.

NOONTIDE heat seeped like treacle through the wire grid and the Venetian blinds. The room sweltered, yet it was cooler than the palm-thatched veranda, where flies kept up a continuous humming and other, less tolerable, pests darted from between the floorboards, while lizards clung motionless to the outer walls, their pulsing visible to the naked eye.

Julian Caswell leaned both arms on his desk and surveyed in turn his two visitors. The mission doctor, grey-faced, grey-garbed, an apathetic dullness in his eyes; and Sister Harrington, poker-backed, her skin a tropic yellow and pitted with the legacy of some disease contracted and mastered in the course of her duties.

“I’ve been on this island just four days,” he said, “and have met plenty of trouble on the plantation, without chasing more among the white population. Surely people of your experience can deal with this girl?”

“If she were the tough type we’d have no difficulty,” the doctor answered. “But she isn’t. From what I remember of her father—he died four years ago in a leopard hunt on the mainland—-he was the typical, well-bred Englishman. I believe her mother came of good South African stock, but the tropics ruined her—morally. After only a few months here with her husband she left the island with another man. The children, this girl and her brother, were educated at boarding-schools in England and South Africa. When the father was killed the son arrived to carry on the shipping agency, and he managed very well right up to his first illness, a year or so ago. Then the girl came, to be with him and help him in the office.”

“And now the young man has died of fever and this child is alone,” Sister Harrington put in sharply. “She lives in a bungalow on the cliffs—with no other companion than a half-breed Portuguese woman servant. An impossible situation for a girl.”

“She has no neighbours?”

“Several, of a type. Bryson, who owns the native store, a forestry man and your own two overseers. No women.”

“You’ve already asked her to live at the mission?”

“Entreated, Mr. Caswell,” the woman corrected him, “and we’ve threatened to demand that the Portuguese authorities send her to British territory—Lagos or Freetown. Unfortunately, although this is a Portuguese island, we seldom see an official and, in any case, I doubt if these people would act. They would cast the onus on to an Englishman, like yourself.”

“Has she any money?”

“More than enough for her needs. It is now two months since young Nigel Crane died, and the agency has been taken over by Burfords. She hasn’t the smallest reason for staying on Valeira.”

“Not what you and I would call a reason, maybe,” said Julian. “How old is she?"

“Seventeen.”

A precocious child who could doubtless do with a spanking. Julian had met the type in Kenya. Sophisticated youngsters, spoiled by a surfeit of men and unrationed drink. They matured into greedy sensualists, like Lilias. Hell, why think of her now?

“What do you want me to do?”

The doctor stirred from his lethargy. “Go and see her, Mr. Caswell. Explain to her the terrible dangers that surround a girl in her position. Both Sister Harrington and I have tried, but perhaps we have not spoken plainly enough, or have failed to emphasize the . . . er . . . appetites of men who are shut off from the diversions of the mainland.”

“I offer her a choice between living at the mission and deportation ... is that it? Her name is Crane?”

“Philippa Crane,” said Sister Harrington, gathering a pair of stringy white gloves from her lap and planting her black laced shoes ready to support her small weight. “I sincerely hope you will succeed in persuading her to go home to England.”

The doctor got up. “We have worried a great deal about the girl. Please get in touch with us after you have seen her.”

Julian promised, and followed them out to the shabby old bush car which, apparently, was driven by Sister Harrington, for the doctor sank into the left seat and assumed a comatose posture, his head dipped into his shoulders, his hands slack between his knees. Half doped, thought Julian, without emotion. At thirty-five, with ten years in the tropics behind him, a man does not hesitate to label symptoms and shrug off the victims. It was each for his own skin in this steaming Hades.

He came back to the living-room and poured whisky and water. For the next six months he needed labour, plenty of it The cacao groves had to be cleared of fierce growths of weeds, the trees pruned and stripped of neglected pods. Then there were the oil palms to be exploited and increased numerically, and other markets to be opened.

Work. Months, years of it. Well, that was what he had come here for. Work and solitude. Freedom from clubs and polo-playing, from drink parties and scandals. Freedom from women like Lilias and their rank-tasting aftermath. You don’t find such women in the West African islands, where the plantations are chiefly owned by Portuguese, and the daily dose of quinine is indispensable.

There was little on Valeira to attract the idle traveller, and much to deter him. At many points on the West African coast he could enjoy the same atmosphere of lush palms and prodigal vegetation against a background of perpetually roaring surf, with far less risk to health and mental balance.

He swallowed his drink and called the houseboy to dispose of the tumblers on the desk. Then he had lunch—a peppery soup, fish and the inevitable pawpaw salad—and soon afterwards drove straight through the estate to where Drew, the chief superintendent, was finishing his sandwiches and beer beneath the shadowy branches of a rubber tree.

Drew was small and sandy, a little younger than Julian and vague about everything but his job. Mr. Caswell measured perfectly to his idea of a boss. The height and width of shoulder, the lean dark features that sometimes appeared deceptively weary, the authoritative air and unsmiling mouth, combined to impress Drew profoundly. In four days he had fallen completely under the spell of Julian Caswell.

They talked of the new track and the division of labour over the tasks before them.

“Send Crawford to the mainland for more men,” said Julian. “Three hundred men on a six months’ contract, the usual wages, housing and medical service.”

“Crawford’s never done it before,” Drew told him. “We’ve always got our labour through Matt Bryson.”

“The trader? What’s his standing on the plantation?”

“He hasn’t any. Matt moved in years ago, built the store and has run it ever since. He has friends among the skippers of the freighters.”

“All the same, I think we’ll send Crawford this time. He strikes me as weakish, and the responsibility will stiffen him.” Julian paused. “You and he live together, don’t you?”

“We share one of the houses on the cliff.”

“Get along all right?”

Drew nodded. “He has moods, but he’s only twenty-six.”

“What sort of moods?”

“Nerves. He doesn’t drink much.”

Nerves, in a fellow of twenty-six. Julian remembered something. “There’s a girl living near you—Philippa Crane. D’you see much of her?”

“No, she stays home every night. Crawford likes her, but she’s just a kid. Bryson’s her closest neighbour; then Clin Dakers, the forestry man.”

Julian said: “Tell Crawford to come and see me first thing in the morning. He’d better have a couple of weeks’ leave in Lagos, and get it out of his system. He can recruit labour for us at the same time.”

He left the car and mounted one of the hefty mules that were tethered near the track. The going was exasperatingly slow, through bamboo thickets, skirting young forests of tree ferns, sparing a glance now and then for the criminally neglected cacao.

It was late when he completed his tour of the plantation, which here was scarcely distinguishable from the primeval jungle that surrounded it. The early darkness had already fallen. His car stood where he had left it, and Drew had thoughtfully had a space hacked bare, so that he could reverse. At the house he took a bath and got into fresh shorts and shirt. The boy, one he had picked up at Cape Palmas and brought to the island, had braised a chicken and cooked rice and brown beans to go with it. The local coffee was good; it had a richer flavour than the stuff he’d grown in Kenya, or perhaps it was mellowed by the sense of isolation from his fellow-beings.

He knelt in front of the bookshelves and chose a novel. He had decided on two hours’ relaxation every evening, and though reading fiction was not one of his vices, it would have to do till he was more established and able to follow more agreeable pursuits. Passing the desk, he saw the notepad scrawled with words and figures, and bent to read. Half-way down, between a reminder about supplies and a query on kola nuts, he saw the name “Philippa Crane.”

Julian lit a cigarette and walked to the wire-screened doorway. Some time he would have to go and see this girl and make her realize the nuisance she had become. The mission people were right. You couldn’t allow a girl to live alone among men in any climate, let alone that of Valeira. And Bryson next door. A middle-aged, pot-bellied trader who was reputed to have an apricot-skinned “wife” over on the Novada estate, the other side of the mountain. Oh yes, Julian had heard most of the gossip on his first day, from the voluble little Latin who had welcomed him: Rodrigo Astartes, owner of the Novada cacao plantation.

He thrust open the screen with his foot and went out to the veranda. The miraculous coolness drew him down on to the path, which widened at the storehouse into the plantation track. Tonight, he followed the narrow trail through the trees which led to the shore. Leaving the rough dip to the waterfront, he turned left up the slope towards the scattered houses which overlooked the beach from a long, low promontory. All showed lights, a couple brilliant, the others dim, as though the occupants were out card-playing or drinking with neighbours.

As Julian climbed it came to him that the nearest bungalow, glowing brightly from every window, was the Crane girl’s. A smart place, what he could make out of it between the black fans of the palms in the garden. Why not call on her now and get it over?

He pushed open the gate, walked along a straight, weed-free path and up the veranda steps, gave two crisp knocks on the white wooden door, and waited. After a couple of minutes he tapped again, more peremptorily. Another minute ticked by and he slid back his cuff to see the time. A quarter to nine. Quite early yet.

The door swung in about eighteen inches, and a girl stood in the opening. A slim girl in a short yellow skirt and white blouse, her hair a tawny cloud around a small pale-gold face. Her eyes were large and fixed upon him, her red mouth had straightened determinedly.

“Good evening,” he said pleasantly. “You may have heard of my arrival—Julian Caswell, the new manager of the plantation....”

He had got so far before realizing that the girl was clasping a tiny little automatic, and had levelled it slightly left of the third button of his shirt.

PHIL spoke in a sweetly husky voice. “I’m sorry to greet you like this, but I never entertain after dark. I have nothing whatever to do with the plantation, but if you wish to see me about something, please call again tomorrow.”

“Put up the weapon, child,” he said curtly. “I’ve no designs on your virtue. If I ever have the urge again to kiss a woman—which is highly improbable—she won’t be a seventeen-year-old. I want a chat with you.”

“I’m sorry,” she repeated. “If you come any nearer I shall shoot. So please go.”

Julian, of course, had no intention of going. He ducked, swiped at her hand and caught the gun as it fell. The next second his foot was jammed between door and frame, and he entered the hall nonchalantly, his smile cool and appraising.

The girl took it well. With a slight shrug she indicated the door to the lounge and went in ahead of him. Julian crossed to the half-open drawer of a writing-table and dropped the automatic inside.