Unknown

Authors: Unknown

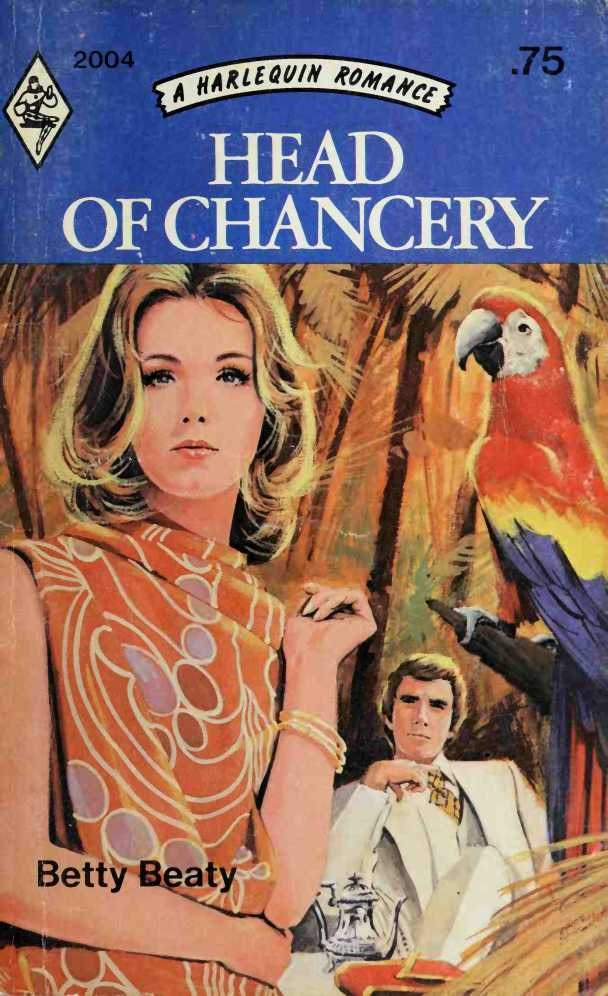

HEAD OF CHANCERY

Betty Beaty

Madeleine’s job at the British Embassy in a Latin American country was fascinating and challenging-- but marred by the harshly critical attitude of one of the senior officials, James Fitzgerald. Unfortunately, a series of mishaps confirmed his low opinion of her.

But were they really mishaps, or something far more sinister?

‘There is, I assure you,

senorita

, no cause for alarm.’

A deep voice came from just behind my left ear as a terrifying upcurrent hit our small inter-state aircraft and seemed about to turn it upside down. There was a shower of coats and luggage from the racks. And before I had time to grab my handbag, off it went from the empty seat beside me, bouncing and ricocheting down the aisle, scattering make-up, passport, my special security card along with a cascade of paper cups that had broken loose from the galley.

‘Our Latin American pilots are well used to such natural upheavals,’ continued the deep voice.

Then in defiance of the

Fasten Seat Belts

sign in Spanish and English, and despite the dangerous gyrations of the little Fokker Friendship, the owner of that deep voice unstrapped himself from the seat behind and got to his feet. I turned and looked up at him curiously. I saw a tall aristocratic man of about twenty-eight whose appearance uncannily matched his voice. His face was thin and deeply tanned. His nose was high- bridged and arrogant. Yet there was a compelling warmth in the large bold brown eyes, and in the sensuous full lips. ‘Not so, it would seem our cabin staff,’ he added, as the young second steward tried with the humility of the already defeated to get him to sit back into his seat.

Bestowing a look of aristocratic disgust at the paper cups bouncing in the continuous turbulence, the stranger picked his way with catlike grace and agility down the aisle. And as if it were the most important task in the whole world, regardless of danger, regardless of weather, one by one he retrieved the contents of my handbag.

My inexpensive and quite dispensable lipstick had come to rest beside a stout South American lady’s shoe. Carefully, courteously, he retrieved it. And before dropping it back in my bag, he tested that the cap was screwed on properly. The same with my change purse. The same with my wallet. The same with my passport. He flipped through the pages to smooth them, lingering perhaps a little longer than necessary on the page of my personal description. But Charaguayans, I had been warned in my hasty Foreign Office briefing, are by nature as curious as children. Then having made elaborately sure that he had returned everything, the aristocratic stranger returned to my side.

‘Your handbag,

senorita.'

He bowed deeply and laid the bag with almost reverent care on my lap.

Almost

reverent, almost irreverent, for a slight piquant mockery edged his old-world manners.

‘Oh, thank you.' I blushed furiously, quite unused in my seven years’ sojourn among civil servants to this sort of attentive treatment. It made me feel like a princess instead of a temporary Embassy secretary. ‘That was very kind of you.’

‘Not at all,

senorita

. Rather was it kind of our mighty Andean storm gods to grant me the opportunity to render the beautiful

senorita

some humble service.’ His mouth as he spoke remained in an expression of the utmost gravity. But there was a mischievous spark deep in those bold brown eyes that lit a dangerous answering spark in me.

The aircraft still continued its gyrations. To steady himself, the stranger laid an elegant hand on the back of the seat. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the two harassed stewards in excited conclave as to how to get this self-willed passenger back into the safety of his seat again.

‘Thank you,’ I repeated. ‘But oughtn’t you to sit down?’

The stranger immediately took that as an invitation. ‘I am greatly honoured. The

senorita

is more than kind.’

With a deep but more hasty bow, he slid himself into the empty seat beside me. With exaggerated rectitude he fastened his seat belt. He turned and nodded to the two stewards, who threw up their hands in the air and beamed at his gracious kindliness, in thus complying with the aircraft rules. Then he clasped his hands and stared fixedly in front of him. His face wore the solemn yet secretly gloating expression of a schoolboy who is unrepentantly aware that he has won on a foul.

For several seconds while the rain rattled audibly above the noise of the twin jets, this handsome stranger said nothing. Outside the grey clouds multiplied. Intermittently the little red navigation light on the end of the wing was drenched out like a drop of paint by the tropical downpour. A force like a herd of charging rhinos kicked the floor under our feet.

Not an experienced traveller, I averted my eyes from the daunting prospect outside and studied the stranger’s profile. Certainly it was handsome and intriguing enough to distract me. It was a face of contradictions. A sensitivity and tenderness about the mouth contradicted the hauteur of the arrogant profile. Lines of laughter cut deep into the thin cheeks belied a certain melancholy droop to the hooded eyelids and the sombre sadness in the brown eyes. A man of quick moods and mercurial temperament. A man used to getting his own way, as witness just now. But so charmingly that no one, or almost no one, would mind.

Besides, there was about him a certain air. Panache. He wore an expensive but discreet lightweight suit of cream linen and a chocolate-coloured silk shirt, a carefully tied silk cravat. His hair was well groomed with half sideburns into the sculpted cheeks.

‘And now,

senorita

,’ the young man turned suddenly to face me, his white smile vivid against his sunburned skin, ‘that you have had time to, how shall I say, digest me, I ask that you check in your handbag to see that all your contents are safely within.'

‘I’m sure they will be, thank you.’

‘Nevertheless,

senorita,

for my sake, please, will you check. Latin America is a very mysterious part of the world. Where things and people disappear,’ he spread his well-shaped hands, ‘just like that!’

Obediently I opened my handbag, one of the few new things I had time to buy for my first assignment outside the U.K. I studied my possessions in order of priority. First my security card which all members of the Embassy staff, no matter how humble, must carry. Then my passport, and my personal things, my mother’s latest, lyrically happy letter from Sydney, my make-up, my key ring. If people and things really did disappear in this strange continent as the stranger laughingly suggested, then neither Madeleine Bradley nor her worldly goods would cause any visible hole.

‘Are they all,

senorita

, as they say, present and correct?’ It was an odd expression for him to use.

‘Everything, thank you.’

‘I spent some time,

senorita

, at your excellent military establishment in Sandhurst. Do you know it?’

‘I know

of

it. We used to live about twenty miles from there, at Epsom.’

‘So,’ he smiled delightedly, ‘we have much in common. In fact immediately I saw you I had a feeling here,’ he touched the breast pocket of his well-cut jacket, ‘in my heart, that we had met before. Perhaps, how does the English melody go . . . across a crowded room?’

‘I doubt it.’ I explained that my life had really been very quiet and circumscribed. Until his death, sixteen years ago, my father had been employed by the Commonwealth Office. He had died in Singapore when I was nine.

‘Did you have brothers to take over the guardianship of your mother and yourself?’

‘No. There were just the two of us. But we managed. I got a job as a typist in the Foreign Office when I was eighteen, and I’ve been there ever since.’

‘Were there no, how shall I say,

landslides

in your life?' As a Latin American he was obviously disappointed with the even tenor of our existence.

I told him that until a year ago, everything seemed as if it would stay exactly as it was. Then the unexpected had happened. My gentle, rather timid mother, who rarely went out from our flat, except to shop, and once a week to take tea with an old school friend, had deposited the contents of a torn rain-soaked carrier bag at the feet of an Australian hotelier then on holiday in London. To some people it might seem unromantic that love should have blossomed between them as she and her genial Australian retrieved oranges and apples from the wet London pavement.

I recounted their whirlwind courtship, my mother’s shy and astonished delight that this totally unlooked-for joy should come her way, her departure for Sydney and her obvious happiness there. Some part of me— I suppose the part well-trained by civil service routine— must have registered that not for years had I spoken to anyone of my own generation so fully. But travel, I’m told, does this to people, and this was my first really long journey.

‘I think that is a most romantic way to meet. A dropped bag, you say? How coincidental,' and seeing the embarrassed colour rise in my cheeks, changing the analogy, ‘Chasing the apples is quite a classical courtship. Like Atalanta, and her golden apples, yes?'

I smiled.

‘And do you notice,

senorita

, how often in life, much comes of a chance meeting?’

I shook my head.

‘But you will notice by what sudden unexpected twists Fate takes us by surprise.'

‘Yes, that’s true.'

‘And now I suppose that you yourself,

senorita

, are flying out to love and marriage in our beautiful Charaguay?’

‘No.’

‘Will there be no young man eagerly awaiting you at the airport?’

‘None,’ I smiled. ‘Not even if Fate takes a sudden unexpected twist.'

The stranger affected not to believe me.

'No romantic reason

at all

for this flight?'

I shook my head. ‘Nothing more romantic than to replace the Ambassador’s secretary. Eve Trent . . . that’s her name . . . had a skiing accident. The poor girl will be in hospital for the next six weeks.'

I thought it all would sound very prosaic to the dashing stranger. Yet I could hardly have caught his interest more. I surprised a shrewd sharpness in the liquid brown eyes And though he expressed polite formal sympathy for the absent Miss Trent, he couldn’t quite swallow a small smile.

Of triumph, I think.

He waited till we flew out of the storm, and the sun burst through the thinning cloud before he spoke again.

‘And now will you give me your permission to present myself to you,

senorita?'

He took my hand, lifted it to just short of his lips and bowed low over it. ‘I am Ramon de Carradedas. Don Ramón at your service,

senorita

.’

‘And I’m....'

‘I know,

senorita.

You are Madeleine Bradley. Madeleine is a beautiful name. But I will christen you one even more suitable—a Charaguayan name:

Madruga.

It means the golden dawn. The dawn is very special in our mythology.’ He paused. ‘And I feel you are very special too.’

Totally out of my depth, I fell back on my British reticence and said nothing.

‘I know that you flew by the British Airways flight to Bogota and then caught this Charaguayan service to Quicha. And that your ticket was booked “in haste”.'

I smiled.

‘I know also that you are five feet three in height, and of slim build and fair complexion. Because it says so in your passport, and these facts are correct.’

Surprised, I exclaimed, ‘You read a great deal in a short time.’

‘Oh, I can if I wish read more and faster than that,

senorita

. But for the rest, your passport is not worth reading. It is incorrect. It could indeed be said to

lie.'

‘How?’

‘Brown hair.’ Don Ramón shook his head. ‘Blue eyes.’ The fastidious nose wrinkled. ‘While I can very well see for myself that your hair, when the sun catches it so, is the colour of Inca gold. And your eyes ...’ His face came close to mine. He stared so fixedly into my eyes that I could see the little dancing gold flecks in his. His expression was that of a connoisseur. For a moment he seemed lost for the right words. Then inspiration visibly came. ‘Tell me,

senorita

, have you heard of a most beautiful lake high in the Andes called Lake Titicaca?'

‘I’ve seen it on the map.’

He seemed disappointed by my mundane reply, but he continued, ‘And you have heard of its beauty?’

‘A little.’