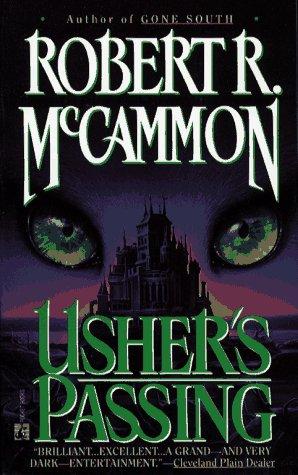

Usher's Passing

Authors: Robert R. McCammon

Tags: #Military weapons, #Military supplies, #Horror, #General, #Arms transfers, #Fiction, #Defense industries, #Weapons industry

Books by Robert R. McCammon

Baal

Bethany's Sin

Blue World

Boy's Life

Gone South

Mine

Mystery Walk

The Night Boat

Stinger

Swan Song

They Thirst

Usher's Passing

The Wolf's Hour

Published by POCKET BOOKS

POCKET BOOKS

POCKET BOOKS

New York London Toronto Sydney Tokyo Singapore

The sale of this book without its cover is unauthorized. If you purchased this book without a cover, you should be aware that it was reported to the publisher as "unsold and destroyed." Neither the author nor the publisher has received payment for the sale of this "stripped book."

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

POCKET BOOKS, a division of Simon & Schuster Inc. 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

POCKET BOOKS, a division of Simon & Schuster Inc. 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 1984 by Robert R. McCammon

Published by arrangement with Henry Holt and Company, Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Henry Holt and Company, Inc. 115 West 18th Street, New York, NY 10011

ISBN: 0-671-76992-8

First Pocket Books printing October 1992 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

POCKET and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Cover art by Kirk Reinert Printed in the U.S.A.

To Michael Larsen and Elizabeth Pomada

I dread the events of the future.

—

Roderick Usher

The Devil's passing.

—

Old Welsh expression for calamity

I

THUNDER ECHOED LIKE AN IRON BELL ABOVE THE SPRAWL OF NEW

York City. In the heavy air, lightning crackled and thrust at the earth, striking the high Gothic steeple of James Renwick's new Grace Church on East Tenth Street, then sizzling to death a half-blind drayhorse on the squatters' flatlands north of Fourteenth. The horse's owner bleated in terror and leaped for his life as his cart overturned, sinking its load of potatoes into eight inches of mud.

It was the twenty-second of March, 1847, and the

New York Tribune's

weather scholar had predicted a night of "dire storms, fit for neither man nor beast." His prediction, for once, was entirely accurate. Sparks exploded into the sky on Market Street, where the cast-iron stovepipe chimney of a hardware store had been lightning-struck. The clapboard building burned fiercely while a crowd gawked and grinned in its merry heat. Steam-spouting fire engines were delayed, wooden wheels and horses' hooves mired in Bowery ooze. Packs of dogs, rats, and pigs scuttled through the alleys, where gangs like the Dover Boys, the Plug Uglies, and the Moan Stickers shadowed their victims along the constricted, cobblestoned streets. Policemen stayed alive by standing like statues under gas lamps.

A young city, New York was already bursting her seams. It was a riotous spectacle, as full of danger in the hoodlum's blackjack as of opportunity in a spilled purse of gold coins. The confusion of streets led from dockyard to theater, ballroom to bawdyhouse, Murder Bend to City Hall, with equal impartiality, though some avenues of progress were impassable due to swamps of debris and garbage.

Thunder rang out again, and the troubled sky split open in a torrent. It soaked dandies and damsels strolling out the doors of Delmonico's, slammed against the lofty windows on Colonnade Row, and leaked down black with soot through the roofs of squatters' shanties. The rain dampened fires, broke up fights, sped indecent propositions or murderous attacks, and cleared the streets in a sluggish tide of filth that rolled for the river. At least for the moment, the nightly farrago of humanity was interrupted.

Two chestnut Barbary horses, their heads bowed against the downpour, pulled a black landau coach along Broadway Avenue, heading south toward the harbor. The Irish coachman huddled within a soggy brown coat, water streaming from the brim of his low-slung hat, and cursed the decision he'd made early that afternoon to trot his team around to the De Peyser Hotel on Canal Street. If he hadn't picked up that passenger, he thought gloomily, he might now be home warming his feet in front of a fire with a mug of stout at his side. At least he had a gold eagle in his pocket—but what good would a gold eagle be when he was dead with the wet shivers? He flicked a halfhearted whipstrike at the flank of one of his horses, though he knew they would move no faster. Hell's bells! he thought. What was the passenger lookin' for?

The gentleman had boarded in front of the De Peyser, laid a gold eagle on the driver's palm, and told the driver to make all possible haste to the

Tribune

office. Instructed to wait, he'd held the horses until the black-garbed gentleman had reappeared fifteen minutes later with a new destination. It was a long trek into the country, up near Fordham in the shadow of the Long Island hills, while purple-veined storm clouds began to gather and thunder throbbed in the distance. At a rather dismal-looking little cottage, a rotund middle-aged woman with gray hair and large, frightened eyes admitted the gentleman—very reluctantly, it had seemed to the coachman. After another half hour in which a downpour of chilly rain had promised the driver an acquaintance with hot salve and oil of wintergreen, the gentleman in black came out with yet another series of directions: back to New York, as quickly as possible, to a number of tawdry taverns in the most unsavory section of the city. South into the Triangle at night! the coachman thought grimly. The gentleman either wanted a cheap trollop or a brush with death.

As they moved deeper into the lawless southern streets, the coachman was relieved to see that the heavy rain was keeping most of the thugs under wraps. Saints be praised! he thought— and at that instant two young boys in rags came running out of an alleyway toward the coach. One of them, the driver saw with horror, held a brick intended to smash the spokes of a wheel— the better to beat and rob both himself and his passenger. He swung his whip with crazed abandon, shouting, "Go on! Go on!" And the team, sensing imminent danger, surged ahead across the slick stones. The brick was thrown, and crashed against the coach's side with the noise of splintering wood. "Go on!" the coachman cried out again, and kept the horses trotting until they'd left the murderous little beggars two streets behind.

The sliding partition behind the coachman's seat opened. "Driver," the passenger inquired, "what was that?" His voice was calm and steady—accustomed to giving orders, the driver thought.

"Beggin' your pardon, sir, but . . ." He glanced back over his shoulder through the partition, and saw in the dim interior lamplight the man's gaunt, pallid face, distinguished by a silvery, neatly trimmed beard and mustache. The gentleman's eyes were deepset, the color of burnished pewter, they fixed upon the coachman with the power of aristocracy. He appeared oddly ageless, his face free of any telltale wrinkles, and his flesh marble white. He was dressed in a black suit and a glossy black top hat, and his long-fingered hands in black leather gloves toyed with an ebony cane topped by a handsome sterling silver head of a cat—a lion, the coachman had seen—with gleaming emerald eyes.

"But

what?"

the man asked. The driver couldn't peg his accent.

"Sir . . . it's not too very safe in this neck o' town. You look to be a refined, respectable gentleman, sir, and it's not too many of those they gets down here in this part o'—"

"Just concern yourself with your driving," the man advised. "You're wasting time." He slid the partition shut.

The coachman muttered, his beard heavy with rain, and urged the team onward. There was just so much a man would do for a gold eagle! he thought. Then again, it sure would buy some fine times at the bar rail.

Sandy Welsh's Cellar, a bar on Ann Street, was the first stop. The gentleman went in, stayed only a few moments, and then they were off again. He stayed barely a minute in the Peacock, on Sullivan Street. Gent's Pinch, two blocks west, was worth only a brief visit as well. On narrow Pell Street, where a dead pig attracted a pack of scavenger dogs, the coachman reined his team up in front of a rundown tavern called the Muleskinner. As the gentleman in black went inside, the coachman pulled his hat low and pondered a return to the potato fields.

Within the Muleskinner, a motley assemblage of drunkards, gamblers, and rowdies pursued their interests in the hazy yellow lamplight. Smoke hung in layers across the room, and the gentleman in black wrinkled his finely shaped nose at the mingled aromas of bad whiskey, cheap cigars, and rain-soaked clothes. A few men glanced in his direction, sizing him up as a profitable victim; but the strong set of his shoulders and the force of his gaze told them to look elsewhere. The rain and humidity had put a damper on even the most eager killer's energies.

He approached the Muleskinner's bar, where a swarthy gent in buckskin was drawing a mug of greenish beer from a keg, and spoke a single name.

The bartender smiled thinly and shrugged. A gold coin was slid across the rough pinewood bar, and greed flickered in the man's small black eyes. He reached out for the coin—and a cane topped by a silver lion's head pressed his hand to the wood. The gentleman in black spoke the name again, calmly and quietly.

"In the corner." The bartender nodded toward a man sitting alone, absorbed in scribbling something by the light of a smoking whale-oil lamp. "You ain't the law, are you?"