Vaccinated (3 page)

Authors: Paul A. Offit

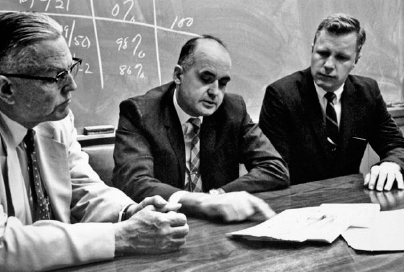

Maurice Hilleman and the pandemic influenza team, Walter Reed Army Medical Research Institute, 1957.

Hilleman knew that he was studying a strain of influenza virus that could sweep across the world unchecked. He also knew that the only way to stop it would be to make a vaccineâand to make it quickly. On May 22, 1957, he sent out a press release claiming that the next influenza pandemic had arrived. “I had a very difficult time getting anybody to even believe this,” remembered Hilleman. “I got a call from Macfarlane Burnet [an Australian immunologist], and he said that you cannot say that this virus is different. Joe Bell [from the U. S. Public Health Service] didn't believe it. He said, âWhat pandemic? What influenza?' How [could] they live in this world and be so stupid?”

Hilleman extended his prediction. Not only did he believe that the virus circulating in Hong Kongânow called Asian fluâwould spread throughout the world, but also he believed that it would enter the United States in the first week of September 1957. “And when I put out a press release stating that there was a pandemic going to come on the second or third day of the opening of school, I was declared crazy,” he said. “But it came, on time.”

While Hilleman was reading the article in the

New York Times

about the influenza outbreak in Hong Kong, the virus was already well on its way to starting a pandemic. The first case of Asian flu had appeared in February 1957 in Guizhou Province in southwestern China. By March it had spread to Hunan Province. Chinese refugees had then carried the virus to Hong Kong. By the end of April, Asian flu had spread to Taiwan, and by early May it had traveled to Malaysia and the Philippines. About two hundred children in the Philippines died of the infection. By late May the virus had spread to India, South Vietnam, and Japan. Mild epidemics occurred on ships of the U. S. Navy, which eventually transported the virus to the rest of the world. Hilleman recalled, “[Navy servicemen] would have an epidemic on board ship, and they would go into town in these ports of call and mix it up with the bar girls and really spread it throughout the Far East.”

Hilleman had shown that Asian flu, which hadn't circulated in the world for seventy years, was back. Thomas Francis, head of the Influenza Commission for the American military, didn't believe him and refused to work on a vaccine. Hilleman remembered, “The military wasn't able to get the Influenza Commission to move. They sent the strains of virus down to Francis's lab, and he said, âWe'll look at it.' [One night] I knew that Tommy Francis was eating [dinner] in town at the Cosmos Club [in Washington, D.C.]. So I sat right beside the door till he walked in. âTommy Francis, I've got to show you something because you're making a huge mistake. We don't have time to fool around.' He looked through the data and said, âMy God, it's a pandemic virus.'”

Hilleman sent samples of Asian flu virus to six American-based companies that made influenza vaccine. He figured that if he were to have any hope of saving American lives, he would have to convince companies to make and distribute vaccine in four months. Influenza vaccine had never been made that quickly. Hilleman sped up the process by ignoring the Division of Biologics Standards, the principal vaccine regulatory agency in the United States. “I knew how the system worked,” he said. “So I bypassed the Division of Biologics Standards, called the manufacturers myself, and moved the process quickly. The most significant thing I told them was to please advise their chicken producers not to kill the roosters or we won't have fertile eggs.” Hilleman knew that the production of millions of doses of influenza vaccine would require hundreds of thousands of eggs a day andâthanks to his background in raising chickensâthat farmers typically killed their roosters late in the hatching season.

As Hilleman had predicted, in September 1957 Asian flu entered the United States from both coasts. The first laboratory-proven cases occurred aboard naval vessels in San Diego, California, and Newport, Rhode Island. A San Diego girl started the first outbreak when she carried the virus to an international church conference in Grinnell, Iowa. The second outbreak occurred in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. “A contingent of Boy Scouts [had come] from Hawaii,” recalled Hilleman, “and they [were] put on the trains and moved from the West Coast all the way back to Valley Forge. An epidemic broke out, and [public health officials] tried to separate the cars and do all sorts of things, but those kids were just laid out everywhere. When they got them to Valley Forge, they put them all in pup tents, and the outbreak stopped.”

Pharmaceutical companies made the first lots of Asian influenza vaccine in June 1957, and vaccinations began in July. By late fall, companies had distributed forty million doses. Asian flu quickly spread across the United States. The National Health Survey estimated that twelve million people were sick with influenza during the week beginning October 13. Within a few months influenza had infected twenty million Americans. Although the 1957 pandemic killed only a fraction of those killed during the 1918 pandemic, the two pandemics shared one sad feature: the disease disproportionately killed healthy young people. During the 1957 pandemic more than 50 percent of infections occurred in children and teenagers, at least a thousand of whom died of the disease.

When it was over, the influenza pandemic of 1957 had killed seventy thousand Americans and four million people worldwide. But Hilleman's quick actions saved thousands of American lives. The surgeon general of the United States, Leonard Burney, said, “many millions of persons, we can be certain, did not contract Asian flu because of the protection of the vaccine.” For his efforts, Maurice Hilleman won the Distinguished Service Medal from the American military. “On that particular day,” recalled Hilleman, “I was told to appear at the White House at 10 a.m. and bring my wifeâand to wear a necktie, for God's sake.”

Hilleman's committee-of-one approach would be hard to duplicate today. No American-based companies make inactivated influenza vaccine; the three companies that provide vaccine to the United States are headquartered in France, Switzerland, and Belgium. And regulatory control of vaccines by the U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would be impossible to ignore.

Â

F

ROM

2003

TO

2005,

DURING THE LAST FEW YEARS OF HIS LIFE,

M

AURICE

Hilleman watched as bird flu spread from Hong Kong outward, eerily reminiscent of what he had seen in 1957. He also watched as bird flu spread from chickens to small mammals to large mammals to people. But months before his death Maurice Hillemanâthe only man to accurately predict an influenza pandemicâmade one more prediction, this one regarding the next pandemic. Understanding his prediction depends on understanding several aspects of influenza biology.

Influenza got its name from Italian astrologers, who blamed the disease's periodic occurrence on the influenceâin Italian,

influenza

âof the heavenly bodies. The most important protein of influenza virus is the hemagglutinin, which attaches the virus to cells that line the windpipe and lungs. Antibodies to the hemagglutinin prevent influenza virus from binding to cells and infecting them. But influenza virus doesn't have only one type of hemagglutinin; it has sixteen. Hilleman was the first to prove that these hemagglutinins change slightly every year. Because the hemagglutinin changes, Hilleman predicted in the early 1950s that protection against influenza would require yearly vaccination. “I could see that with time these viruses kept changing, changing, changing,” recalled Hilleman, “and that this would explain why this virus could come back each year.”

But sometimes influenza virus underwent a change so massive and so complete that no one in the population had antibodies to it. Such a change in the virus could cause a pandemic. Public health officials worry that the bird flu circulating in Southeast Asia since 2003 could be such a strain. Hilleman didn't think so. Bird flu is hemagglutinin type 5, or H5. Although H5 viruses can very rarely cause severe and fatal disease in people, the spread of H5 virus from one person to another is very poor. When Asian flu began in Hong Kong in 1957, the virus quickly spread from person to person, infecting about 10 percent of the population. When bird flu raged through chickens in Southeast Asia in 1997 and again in 2003, only three people caught the infection from another person; everyone else caught the disease directly from birds. Hilleman reasoned that bird flu wouldn't become a pandemic virus until it spread easily among people. H5 viruses have circulated for more than a hundred years and have never been very contagious. Hilleman believed that they never would be. He noted that only three types of hemagglutinins had ever caused pandemic disease in humans: H1, H2, and H3.

Hilleman believed that the future of influenza pandemics could be predicted from past pandemics:

H2 virus caused the pandemic of 1889.

H3 virus caused the pandemic of 1900.

H1 virus caused the pandemic of 1918.

H2 virus caused the pandemic of 1957.

H3 virus caused the pandemic of 1968.

H1 virus caused the mini-pandemic of 1986.

Hilleman saw two patterns in these outbreaks. First, the types of hemagglutinins occurred in order: H2, H3, H1, H2, H3, H1. Second, the intervals between pandemics of the same type were always sixty-eight yearsânot approximately sixty-eight years, but exactly sixty-eight years. For example, an H3 pandemic occurred in 1900 and 1968, and an H2 pandemic occurred in 1889 and 1957. Sixty-eight years was just enough time for an entire generation of people to be born, grow up, and die. “This is the length of the contemporary human life span,” said Hilleman. “A sixty-eight-year recurrence restriction, if real, would suggest that there may need to be a sufficient subsidence of host immunity before a past virus can regain access and become established as a new human influenza virus in the population.” Using this logic, Hilleman predicted that an H2 virus, similar to the ones that had caused disease in 1889 and 1957, would cause the next pandemicâa pandemic that would begin in 2025. Only partially tongue-in-cheek, he declared his prediction to be “of greater predictive reliability than either the writings of Nostradamus or the

Farmers' Almanac

.” When Hilleman made his prediction in 2005, knowing that his death was imminent, he said, “We'll soon know whether I was right or wrong. And I'll be watching. I'll be looking downâor upâto find out what happened.”

F

ollowing the 1957 influenza pandemic, Maurice Hilleman left Walter Reed to become the director of virus and cell biology at Merck Research Laboratories. His goal at Merckâto prevent every viral and bacterial disease that commonly hurt or killed childrenâwas unattainable. For the next three decades Hilleman made and tested more than twenty vaccines. Not all of them worked. But Hilleman came remarkably close to reaching his goal.

Â

O

NE VACCINE ORIGINATED FROM THE BACK OF HIS DAUGHTER

'

S THROAT.

On March 23, 1963, at 1:00 a.m., Jeryl Lynn Hilleman woke up with a sore throat. Five years old, with penetrating blue eyes and an adorable pixie haircut, Jeryl quietly tiptoed into her father's bedroom and stood at the foot of his bed. “Daddy?” she whispered. Hilleman shook himself awake, rose to his full height of six feet one inch, bent down, and gently touched the side of his daughter's face. There, at the angle of her jaw, he felt a lump. Jeryl winced in pain.

At the time of his daughter's illness, Hilleman was a single father. Four months earlier his wife, Thelma, had died of breast cancer. “[Thelma] was the best-looking girl in Custer County High School,” remembered Hilleman. “We were married in Miles City on New Year's Eve, 1944. For our honeymoon, we rode the train from Miles City back to the University of Chicago. When she got breast cancer, it went through her like wildfire. The chemotherapy in those days was crude. I worked during the day and would spend all night with Thelma at the hospital in Philadelphia.”

Although he wasn't sure what was happening to Jeryl, Hilleman had a pretty good idea. Near his bed was a book titled

The Merck Manual

, a simply written compendium of medical information. Thumbing through it, he soon found what he was looking for. “Oh my God,” he said, “you've got the mumps.” Then Hilleman did something that few fathers would have done. He walked down the hallway, knocked on the housekeeper's door, and told her that he would be gone for a while. Then he went back to his bedroom, picked up his daughter, and put her back to bed. “I'll be back in about an hour,” he said. “Where are you going, Daddy?” asked Jeryl. “To work, but I won't be long.” Hilleman got into his car and drove fifteen miles to Merck. He rummaged around his laboratory, opening and closing drawers, until he found cotton swabs and a vial of straw-colored nutrient broth. By the time he got home, Jeryl had fallen back to sleep. So he gently touched her shoulder, woke her up, stroked the back of her throat with the cotton swab, and inserted it into the vial of broth. Then he comforted her, drove back to work, put the nutrient broth in a laboratory freezer, and drove home.

Most parents thought that mumps was a mild, short-lived illness. But Hilleman knew better. He was scared about what might happen to his daughter.

Â

I

N THE

1960

S, MUMPS VIRUS INFECTED A MILLION PEOPLE IN THE

United States every year. Typically the virus attacked the glands just in front of the ears, causing children to look like chipmunks. But sometimes the virus also infected the lining of the brain and spinal cord, causing meningitis, seizures, paralysis, and deafness. The virus didn't stop there. It also infected men's testes, causing sterility, and pregnant women, causing birth defects and fetal death. And it attacked the pancreas, causing diabetes. Although he knew that it was too late for Jeryl, Hilleman wanted to find a way to prevent mumps. He decided to use his daughter's virus to do it.

As with his work on influenza virus, Hilleman turned to chickens. When he got back to his laboratory, he took the broth containing Jeryl's virus and inoculated it into an incubating hen's egg; in the center of the egg was an unborn chick. During the next few days the virus grew in the membrane that surrounded the chick embryo. Hilleman then removed the virus and inoculated it into another egg. After passing the virus through several different eggs, Hilleman tried something else. He took an egg that had been incubating for twelve days and removed the gelatinous, dark brown chick embryo. Typically it takes about three weeks for an egg to hatch, so the embryo was still very small, weighing about the same as a teaspoon of salt. Hilleman cut off the head of the unborn chick, minced the body with scissors, treated the fragments with a powerful enzyme, watched the chick embryo dissolve into a slurry of individual cells, and placed the cells into a laboratory flask. (A cell is the smallest unit in the body capable of functioning independently. Human organs are composed of billions of cells.) Chick cells soon reproduced to cover the bottom of the flask. Hilleman passed Jeryl Lynn's mumps virus from one flask of chick cells to the next and watched as the virus got better and better at destroying the cells. He repeated this procedure five times.

Hilleman reasoned that as his daughter's virus adapted to growing in chick cells, it would get worse at growing in human cells. In other words, he was trying to weaken his daughter's virus. He hoped that the weakened mumps virus would then grow well enough in children to induce protective immunity, but not so well that it would cause the disease. When he thought the virus was weak enough, he turned to two friends, Robert Weibel and Joseph Stokes Jr., for help. Weibel was a pediatrician who worked in the Havertown section of Philadelphia, and Stokes was the chairman of pediatrics at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Stokes, Weibel, and Hilleman then made a choice that was typical of the time but abhorrent today: they decided to test their experimental mumps vaccine in mentally retarded children.

Maurice Hilleman and coworkers Joseph Stokes Jr. (left) and Robert Weibel, circa mid-1960s.

In the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, scientists often tested their vaccines in mentally retarded children. Jonas Salk tested early preparations of his polio vaccine in retarded children at the Polk State School outside of Pittsburgh. At the time of Salk's experiments, no one in the government, the public, or the media objected to such testing. Everyone did it. Hilary Koprowski, working for the pharmaceutical company Lederle Laboratories, put his experimental live polio vaccine into chocolate milk and fed it to several retarded children in Petaluma, California, and a research team at Boston Children's Hospital used retarded children to test an experimental measles vaccine.

Today we see studies on mentally retarded children as monstrous. We assume that scientists viewed retarded children as expendable subjects for their experimental, potentially dangerous vaccines. But retarded children weren't the only ones first subjected to these vaccines; researchers also used their own children. In July 1934, one year before he learned that his ill-fated polio vaccine inadvertently paralyzed and killed children, John Kolmer, working at Temple University in Philadelphia, inoculated his fifteen-and eleven-year-old sons with it. In the spring of 1953, Jonas Salk injected himself, his wife, and his three young children with an experimental polio vaccineâthe same vaccine that he had given to retarded children at the Polk State School.

Jonas Salk inoculates son Jonathan: May 16, 1953 (courtesy of the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation).

Salk believed in his vaccine, and he wanted his children to be among the first to be protected. “It is courage based on confidence, not daring,” he said. “Kids were lined up in the kitchen to get the vaccine,” recalled his wife, Donna. “I remember taking it for granted. I had complete and utter confidence in Jonas.”

And one of the first children to receive Hilleman's experimental mumps vaccine was his second daughter, Kirsten. (Hilleman had remarried late in 1963.)

Why would researchers inject mentally retarded children at the same time that they injected their own children with experimental vaccines? How can one reconcile these two apparently irreconcilable facts? The answer is that retarded childrenâconfined to institutions where hygiene was poor, care was negligent, and space was inadequateâwere at greater risk of catching contagious diseases, and of dying of those diseases, than other children. Retarded children living in large group homes suffered severe and occasionally fatal infectious diseases more commonly than other children. They weren't tested because they were more expendable; they were tested because they were more vulnerable.

Years later, Maurice Hilleman was unrepentant about his choice to test his mumps vaccine in retarded children. “Most children, mentally retarded or not, get the mumps,” he said. “My vaccine gave all of these children the chance to avoid the harm of that disease. Why should retarded children be denied that chance? Retarded children are perceived as more helpless; but their understanding of the shot that they were given, and their willingness to participate in the trial, was no different than [that of] healthy babies and young children. The difference was that retarded children were often wards of the state; their rights weren't protected by their parents. And although I think that states generally did a good job of protecting those rights, there have been abuses. And those abuses eventually changed how we thought about studying retarded children.” Hilleman was talking about Willowbrook.

Robert Weibel injects Kirsten Hilleman with the Jeryl Lynn strain of mumps vaccine, 1966. Jeryl Lynn Hilleman looks on.

The Willowbrook State School was founded in 1938, when the New York state legislature purchased 375 acres of land on Staten Island and authorized the building of a facility for the care of mentally retarded children. Construction was completed in 1942. The residents of Willowbrook were the most severely retarded, the most handicapped, and the most helpless of those being cared for in the New York state system. Although Willowbrook was designed to house three thousand people, by the midâ1950s about five thousand lived there. Jack Hammond, the director of Willowbrook, described the hellish, medieval living conditions: “When the patients are up and in the day rooms, they are crowded together, soiling, attacking each other, abusing themselves and destroying their clothing. At night, in many of the dormitories, the beds must be placed together in order to provide sufficient space for all patients. Therefore, except for one narrow aisle, it is virtually necessary to climb over beds in order to reach the children.”

A small, poorly trained staff coupled with massive overcrowding led to a series of tragedies at Willowbrook. In 1965, inadequate supervision by a teenaged attendant caused a forty-two-year-old resident to be scalded to death in a shower. A few months later, a ten-year-old boy suffered the same fate in the same shower. That same year, a twelve-year-old boy died of suffocation when a restraining device loosened and twisted around his neck. The following month, one of the residents struck another in the throat and killed him. At the end of the year Senator Robert Kennedy paid a surprise visit to Willowbrook. Horrified by what he saw, Kennedy called Willowbrook “a new snakepit” and said that the facilities were “less comfortable and cheerful than the cages in which we put animals in the zoo.” Kennedy's visit prompted short-lived, inadequate reforms. Several years later, following an exposé by WABCTV in New York titled “Willowbrook: The Last Great Disgrace,” legislators finally instituted meaningful reforms. The reporter for the story was a twenty-nine-year-old journalist recently hired by the station: Geraldo Rivera.