Vermeer's Hat (12 page)

Authors: Timothy Brook

The circulation of decorative objects did not go only from China to Europe. European objects and pictures circulated in China

too. On 5 March 1610, while the

White Lion

was on its third voyage from Amsterdam to Asia, and a few years before Wen Zhenheng started writing his

Treatise on Superfluous Things

, an art dealer called Merchant Xia paid a call on a favored customer. Li Rihua was a renowned amateur painter and a wealthy

art collector living in Jiaxing, a small city on the Yangtze Delta southwest of Shanghai. Li moved in the same social circles

as the Wen family and probably knew the author of

Superfluous Things

. He was one of Merchant Xia’s regular customers, having bought paintings and antiquities from him over a long stretch of

years. Xia was just back from Nanjing, the center of the antiques and curiosities trade at the opposite end of the Yangtze

Delta. He brought a selection of rarities for Li to view: a porcelain wine cup from the 1470s; an old bronze water dripper

of the sort calligraphers used to thin their ink, which was fashioned in the shape of a crouching tiger; and two greenish

earrings the size of a thumb. Xia assured Li that the earrings were a rare type of crystal from a kiln that produced such

things only in the 950s, implying that he expected them to fetch a high price.

Li liked most of the things on offer, but he quickly realized that Merchant Xia was wrong about the earrings. He decided to

have fun with Xia by pretending to examine them with due care, and then pointing out that they were made of glass. Not only

were the earrings not tenth-century antiques; they were not even Chinese. As Li wrote in his diary later that day, “These

items were brought here on foreign ships coming from the south—items of foreign manufacture, in fact. The glass objects you

find these days are all the work of the foreigners from the Western [Atlantic] Ocean, who make them by melting stone, and

not naturally produced treasures.” Li enjoyed getting the better of Merchant Xia, but not out of malice. He knew that forgery

was all part of the game of buying and selling antiques, and quite enjoyed the fact that this time it was the dealer who had

been fooled, not the customer. Merchant Xia left suitably chastened, and probably embarrassed more for having paid a high

price for the earrings in Nanjing than for trying to sell them to someone as alert as Li Rihua.

Does this anecdote demonstrate that the Chinese were not curious about foreign objects? Not at all. We have to realize what

Li was doing when he collected. For him, the point of collecting was to discover objects that confirmed the cultural authority

of the ancients; this was why authenticity was so important to him. He wanted things that connected him to better times, which

were always in the past. What the anecdote does show is that foreign articles circulated in China in the seventeenth century.

If they were reaching Nanjing and then circulating out in the hands of traveling dealers to the surrounding cities, there

must have been some sort of market for them. They did not circulate on the scale that foreign manufactures did in Europe,

but then they reached China in much smaller volume. Also, unlike in Europe, where roughly a century of plunder and trade around

the world had trained Europeans into becoming connoisseurs of foreign curiosities, demand for such objects in China was not

well developed. Foreign things were not out of bounds for Chinese collectors. Wen Zhenheng encourages the readers of

Superfluous Things

to acquire certain foreign objects. He recommends brushes and writing paper from Korea, and he advocates owning a wide range

of Japanese objects from folding fans, bronze rulers, and steel scissors to lacquered boxes and fine furniture. Foreign origin

was not a barrier to appreciation.

If foreign objects were a “problem” in China, it was not due to some deeply embedded Chinese disdain for foreign things. It

had to do with the pliable nature of things themselves. Objects of beauty were valued to the extent that they could carry

cultural meanings; in the case of antiques, meanings having to do with balance and decorum and a veneration of the past. Antiques

were valued because they brought their owners into physical contact with a golden past from which the present had fallen away.

Given the burden of meaning that objects had to carry, it was difficult to discern what value to attribute to objects coming

from abroad. Rarity was a quality to be prized, and curiosity about things marvelous or strange was a laudable impulse for

the collector, but the essential impulse for collecting was to bring oneself into contact with the core values of civilization.

This is why Wen could recommend Korean and Japanese objects to his readers. China had a long history of cultural interaction

with Korea and Japan, so Korean and Japanese things could be seen as sharing in the same civilizational ethos as Chinese things.

They were different, but the difference was tame. It did not slide from the odd to the bizarre.

The same could not be said for European things. Li Rihua was not indifferent to knowing about what lay beyond China’s shores;

indeed, his diary includes numerous remarks about what he heard concerning foreign ships and sailors who wandered into Chinese

coastal waters. But the objects coming from foreign lands had no place in his symbolic system. They embodied no values. They

were merely curious. In Europe, by contrast, Chinese things had a greater impact. There, difference became an invitation to

acquire. Europeans felt inclined to incorporate them into their living spaces, and even beyond that, to revise their aesthetic

standards. The dish that Vermeer set in the foreground of

Young Woman Reading a Letter at an Open Window

is a foreign thing, nestled in turn within the Turkish carpet, another foreign thing. These objects stirred no contempt or

anxiety. They were beautiful, and they came from places where beautiful things were made and could be bought. That was all,

and enough to make them worth buying.

If there was a place for such foreign objects in European rooms, there wasn’t in Chinese rooms. This issue was not ultimately

one of aesthetics or culture. It was the relationship with the wider world that each could afford to have. Dutch merchants

with the full backing of the Dutch state were traveling the globe and bringing back to the wharves of the Kolk marvelous evidence

of what the other side of the world might be like. The people of Delft looked on Chinese dishes as totems of their good fortune

and happily displayed them in their homes. Of course they were beautiful, and taking pleasure in that beauty was what Dutch

householders liked to do. But the dishes were also symbolic of a positive relationship to the world.

What did Li Rihua see, as he looked beyond the wharves of his native Jiaxing, other than a coast beset by pirates? From where

he stood, that wider world was a source of threat, not of promise or wealth, and still less of delight or inspiration. He

had no reason to own symbols of that threat and place them around his studio. For Europeans, on the other hand, it was worth

no little danger and expense to get their hands on Chinese goods. Which is why, four years after the sinking of the

White Lion

, Admiral Lam was back in the South China Sea looting Iberian ships and seizing Chinese vessels in the hope of acquiring more.

T

HERE IS ONE painting by Vermeer,

The Geographer

(see plate 4), that requires little effort to locate signs of the wider world that was enveloping and invading Delft. The

painting opens conventionally on the artist’s studio, the same closed space we expect to find in a Vermeer painting where

bright windows again have been painted at an angle so oblique that their panes transmit no image of what lies in the street

outside. This time, however, the room is cluttered with objects that gesture exuberantly to a broader world. The drama that

Vermeer sets on his stage is not about the engagements of love, the theme in the two preceding paintings, or about the drive

for moral perfection, which will animate another painting that we will soon examine. It is about a different drive altogether,

the desire to understand the world: not the world of domestic interiors, or even of Delft, but the expansive lands into which

traders and travelers were going and from which they were bringing back wondrous things and amazing new information. The things

engaged the eye, but the information engaged the mind, and the great minds of Vermeer’s generation were absorbing it all and

learning to see the world in fresh ways. They were making new measurements, proposing new theories, and building new models

on scales that stretched macroscopically as far as the entire globe and microscopically into the mysterious depths that were

beginning to be revealed in a drop of rain or a mite of dust.

This is what

The Geographer

is about. It is no surprise, then, that it evokes in the viewer a mood different from those of Vermeer’s other paintings.

He has characteristically constructed the canvas around a figure who is absorbed in his own doings and is not posing for the

viewer. Still, the sense of intimacy of the other paintings isn’t there. We are drawn to the geographer as he pauses to cogitate,

just as we are drawn to the young woman who reads her letter, but we don’t really enter onto a deeper plane of reflection.

Perhaps with

The Geographer

(and its companion painting,

The Astronomer

) Vermeer intended to move into new subject matter but hadn’t quite figured out how to make the intellectual drama an emotional

experience for the viewer. The passion to know the world by mapping it was not quite as compelling for viewers, or the artist,

as the passion to know another person through love. Perhaps the paintings were commissioned by a buyer who fancied owning

images of the new thirst for scientific knowledge, which left Vermeer feeling undermotiviated. Indeed, perhaps they were commissioned

by the man who posed for them, by best guess the Delft draper, surveyor, and polymath, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek.

Leeuwenhoek’s surname was his address: “at the corner by Lion’s Gate,” which was the next gate to the right of the pair of

gates shown in

View of Delft

. He is best known for the experiments he conducted with lenses, for which he is credited today as the father of microbiology.

No documentary evidence directly links Vermeer and Leeuwenhoek, yet the circumstantial evidence that they were friends is

strong. The fact that the two men were born in the same month, lived in the same part of town, and had friends in common might

not be enough to convince the skeptical. But Leeuwenhoek played a key role after Vermeer’s death. Vermeer died when his business

as a painter and art dealer was at a low ebb. His widow, Catharina, had to file for bankruptcy two months later, and when

she did, the town aldermen appointed Leeuwenhoek to administer the estate. Judging from a later portrait, the man who has

pushed back the Turkish carpet on the table and bends over a map with a set of surveyor’s dividers in his hand is Leeuwenhoek.

Even if he weren’t, Leeuwenhoek was just the sort of person the painting lionizes.

The signs of the wider world are everywhere. The document that the geographer has spread out before him is indecipherable,

but it is clearly a map. A sea chart on vellum is loosely rolled to his right under the window. Two rolled-up charts lie on

the floor behind him. A sea chart of the coasts of Europe—the subject becomes apparent when you realize that the top of the

map points west, not north—hangs on the back wall. The original of this sea chart has not been found, but it is similar to

one produced by Willem Blaeu, the commercial map publisher in Amsterdam who printed the map on the back wall of

Officer and Laughing Girl

, among many others. A terrestrial globe literally caps the entire painting. This is Hendrik Hondius’ 1618 edition of a globe

his father Jodocus first published in 1600.

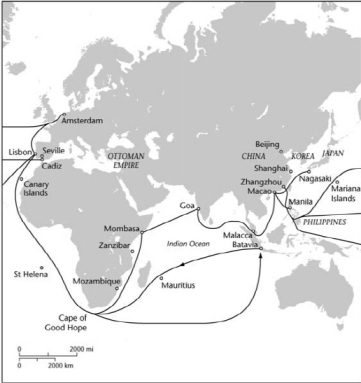

Vermeer includes just enough detail on the Hondius globe to show that it is turned to expose what Hondius calls the Orientalus

Oceanus, the Eastern Ocean, which we know today as the Indian Ocean. Navigating this ocean was a great challenge for Dutch

navigators in the opening years of the seventeenth century. The Portuguese route to Southeast Asia ran around the Cape of

Good Hope and up past Madagascar, following the arc of the coastline. This route had the advantage of many landfalls, but

it was hampered by unfavorable currents and winds and was under Portuguese control, however unevenly defended. In 1610, a

Dutch mariner discovered another route. This involved dropping down from the cape to 40 degrees southern latitude and picking

up the prevailing westerlies, which, combined with the West Wind Current, could speed a ship across the bottom of the Indian

Ocean, then veering north to Java on the southeast trades, by-passing India entirely. The route to the Spice Islands was thereby

shortened by several months.

The cartouche (the ornamental scroll with an inscription that many a cartographer of the time used to fill in the empty areas

of a map) on the lower part of the globe is illegible in the painting, but can be read on a surviving copy of this globe.

In it Hondius has printed in his defense a brief explanation as to why this globe differs from the version he published in

1600. “Since very frequent expeditions are started every day to all parts of the world, by which their positions are clearly

seen and reported, I trust that it will not appear strange to anyone if this description differs very much from others previously

published by us.” Hondius then appeals to the enthusiastic amateurs who played a significant role in compiling this knowledge.

“We ask the benevolent reader that, if he should have a more complete knowledge of some place, he willingly communicate the

same to us for the sake of increasing the public good.” An increase in the public good was also an increase in sales, of course,

but no one at the time minded the one overlapping the other if that made the product more reliable. There was a new world

out there, and knowledge of it was worth paying for, especially as one of the tangible costs of ignorance was shipwreck.

THE SPANISH JESUIT Adriano de las Cortes experienced the consequence of having less than “complete knowledge” of the South

China Sea on the morning of 16 February 1625, when

Nossa Senhora da Guía

was driven onto the rocks of the Chinese coast. The

Guía

was a Portuguese vessel on its way from the Spanish colony of Manila in the Philippines to the Portuguese colony of Macao

at the mouth of the Pearl River. The ship had departed from Manila three weeks earlier, tacking up the west side of the island

of Luzon and then heading west across the South China Sea to China. On the third day crossing the open water, a cold fog becalmed

the ship. The navigator should have carried the charts he needed to make the well-traveled crossing from Manila to Macao,

but charts were only as good as the bearings he could take from the sun and stars. The combination of fog, slowdown, and drift

defeated him. Approximating his distance from the equator was not too difficult, but estimating where the ship was between

east and west was impossible. (The instrumentation needed to determine longitude at sea was not developed for another century

and a half.) The wind came back up two days later, but then it whipped into a gale so fierce that it blew the ship even farther

off its course. The

Guía

’s pilot had no way to reckon their position and could do nothing but wait until land came into sight and try to figure out

their location from the profile of the shoreline.

GLOBAL TRADE ROUTES IN

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

Two hours before dawn on 16 February, the gale unexpectedly drove the ship onto the China coast. The place was uncharted and

unknown to those on board. Only later would the survivors learn that they had run aground three hundred and fifty kilometers

northeast of their destination, Macao. The water where the ship broke up was shallow enough that most of the over two hundred

people taking passage on the

Guía

were able to get to shore. Only fifteen failed to make it: several sailors, several slaves (one of whom was female), a few

Tagals from Manila, two Spaniards, and a young Japanese boy.

The inhabitants of a nearby fishing village came down to the shore to stare at the host of foreign people coming ashore, giving

them a wide berth as they scrambled out of the waves. Most may never have seen foreigners at close range before, as this spot

on this coast was off the two main sea-lanes handling foreign trade, one from Macao to Japan, and the other to the Philippines

from Moon Harbor (now Amoy), which lay two hundred kilometers in the opposite direction from Macao. The fishing people living

along this coast were aware that foreigners were sailing in these waters. They would have heard about the Portuguese in Macao

(official Chinese discourse called them the Aoyi, the Macanese Foreigners) and known that they were unlikely to be attacked

by these people. Those they feared were the Wokou, or Dwarf Pirates (the colloquial term for Japanese), and the terrible Hongmao,

or Red Hairs (a recently coined name for the Dutch). Dwarf Pirates had been raiding the coast for a century in reaction to

the Chinese government’s 1525 ban on maritime trade with Japan. They were feared for their skill as swordsmen. Local people

still told the story of a dozen sword-wielding Japanese who managed to kill three hundred Chinese militiamen sent against

them. The Red Hairs excited an even greater fear. The Dutch had been preying along this coast only in the last two or three

years but they had quickly established a reputation for being violent and dangerous. The Chinese name for these people tells

us what most struck Chinese when they saw Dutchmen. Among Chinese, black is the normal color for hair. As Portuguese tended

also to be dark haired, they were considered simply ugly rather than bizarre. The same could not be said for the Dutch, whose

blond and reddish hair was a shock to Chinese eyes. Anyone with hair this color was a Red Hair, and therefore Dutch, and therefore

dangerous.

Red Hairs, Dwarf Pirates, and Macanese Foreigners were not all that came ashore. Scattered among them were another category

altogether: Heigui, or Black Ghosts. These were the African slaves who worked as servants of the Portuguese and who were ubiquitous

in the European colonies in East Asia. Truly unlike any person the Chinese had ever seen, they were feared above the rest.