Victoria & Abdul (20 page)

Authors: Shrabani Basu

The Queen, a strict moralist, had however refused to receive Duleep Singh’s second wife, his former mistress Ada Douglas Wetherill, on the grounds that he was living with her when he was still married to his first Maharani. The Queen had been very fond of Duleep Singh’s first wife, Maharani Bamba, and disapproved of Duleep Singh’s disregard for her. With the painful chapter of Duleep Singh resolved, the Queen spent a few more relaxed weeks in Grasse, even buying a she-ass for her donkey chair. The she-ass would travel back with her to England and give welcome relief to Pierrot, the Queen’s Scottish donkey, who was getting on in years.

![]()

The Munshi’s fame had by now spread in Britain. His name figured regularly in the Court Circulars as he accompanied the Queen and attended royal dinners, levees and theatricals. The circulars would always mention him as ‘the Queen’s principal Indian secretary’, along with the rest of her suite. Muslims living in Britain wanted to see the man who walked in the charmed Royal circle and was so close to the Queen. It was a custom with Karim and the Indian attendants that after the holy month of Ramadan – throughout which they would observe their strict fast – they would go to the Shah Jahan mosque in Woking to pray at Id. The mosque in Surrey, about thirty miles west of London, had been built in 1889 by an orientalist named Dr Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner, born of Jewish parents in Hungary, who had lived for several years in Istanbul, London and India and was a professor of Arabic and Islamic law. In 1883 he had acquired the site of the Royal Dramatic College, a large Victorian building in

extensive grounds in Woking, and started the Oriental Institute there. With funding from the Begum of Bhopal, a purpose-built mosque was soon constructed on the site, complete with pillars and a dome. Designed to look somewhat like the Brighton Pavilion, it became the first mosque to be built in Britain, and the first outside Moorish Spain in Europe.

The custom of Id prayers at the Woking mosque was followed by Karim every year, and

The Birmingham Daily Post

observed in an article in May 1891 that ‘they are met on the occasion by Mohammedans from all parts of England, who come to see the Munshi and join him in prayer’. The Munshi, who was a Hafiz (one who has memorised the entire Quran) was also invited to conduct the prayers at the mosque.

There is evidence that Indians travelling in Britain were often curious to see the Munshi and many wrote to him and visited him. Some came to him for help. One of these visitors was Raj Bahadur, cousin of Jawaharlal Nehru (later to become India’s first Prime Minister) and nephew of Motilal Nehru (Jawaharlal’s father). He was the son of Bansidhar Nehru, second brother of Motilal Nehru. Raj Bahadur’s aunt, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit (Jawaharlal’s sister), recorded in her memoir

The Scope of Happiness

that Raj Bahadur was an adventurer and had left home at a young age, leaving his wife and daughter to be looked after by the joint family. He wandered around Europe and America and, finding himself in straitened financial conditions, wrote to the Munshi and became acquainted with him. He even got employment under him for some time.

Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit had been told this story by her father Motilal Nehru. Later she became India’s High Commissioner in London and wrote:

I tried to check on this during my years in London, but all I could find out was that young Indians did go to the Munshi from time to time, probably to help or be helped by him, but there were no names available. Anyway, it’s a nice story.

![]()

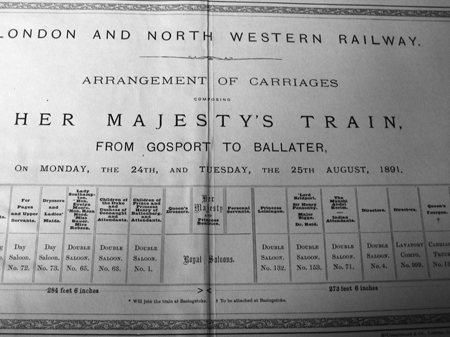

The Queen was a great traveller. She enjoyed nothing more than sitting in her train and watching the countryside go by. She loved her visits to Europe, despite her advancing years, and always managed to pack in several engagements and meet her extended family. Barely a month after returning from Grasse, she left for Balmoral. The entourage travelled from Windsor to Derby and then to Ballater on 21 May 1891. The Munshi now travelled in luxury, solely occupying the whole of the fifth carriage on the Royal train, according to the Court Circular in

The Times

. His pre-eminent position in the Court can be judged by the fact that the adjoining fourth carriage had in it only the four senior-most members of the Household: Dr Reid, Alick Yorke, Lord Edward Pelham Clinton, Master of the Household, and Maurice Muther.

A document showing the arrangement of the Royal train carriages.

At Balmoral, the Queen often took her Hindustani lessons in the Summer Cottage within the grounds of the estate, a short distance from the castle. She would drive out in her carriage, the Munshi walking behind. The Queen enjoyed the company of the Indian Princes, like the Maharajah of Cooch Behar and the Maharajah of Kapurthala, who dropped in to see her over the summer in Balmoral. The Indian Royals always excited the reporters and locals on account of their exotic clothes. A reporter from the

Dundee Evening Telegraph

, who was going to see a

production of

Mikado

at Balmoral, ran into one of the Royal carriages with outriders taking an Indian Prince to the station from Balmoral. He wrote next day: ‘The bright turbans of the Prince and his people are to be seen for a mile or so as we look back, adding their “iota” to the rich colouring.’

8

The Queen had by now begun to plan an extension to Osborne House to accommodate a special Indian room to be named the Durbar Room. The sixty-foot long, thirty-foot wide and twenty-foot-high room was to be built adjacent to the pavilion and used as the much-needed Banqueting Room. It would be connected to the main house by a long corridor called the Indian corridor, where the Queen planned to have portraits of her favourite Indians on the wall, busts that she had commissioned and some of her prized Indian crafts. She had already met the architect, Bhai Ram Singh, Master of the Mayo School of Art in Lahore, who had been recommended to her by Sir Lockwood Kipling, Curator of the Lahore Museum and father of Rudyard Kipling. Lockwood Kipling had been commissioned by several Indian Princes to build an Indian-style Billiard Room in Bagshot Park, the Royal hunting lodge eleven miles from Windsor, as a special wedding present for Prince Arthur, the Duke of Connaught, and the Duchess, Princess Louise. The Queen had seen the Billiard Room and always wanted an Indian room herself. The decorations for the room were all made in India and the walls and ceiling faced with wooden panels carved by craftsmen in Lahore. It was Bhai Ram Singh who had created and executed the designs at Bagshot and had travelled with Kipling to England to see the installation of the room. When the Queen contemplated the Indian room at Osborne, Lockwood Kipling suggested that she employ Bhai Ram Singh to supervise the work. Owing to the high cost of bringing in decorators from India, it was decided that Singh would create the designs and supervise their craftsmanship by British craftsmen, though both the Queen and Princess Louise privately had their doubts about whether they would be able to carry out the work to the same standard.

Eventually, the plaster decorations were made by George Jackson and Sons from London. Princess Louise suggested that the fireplace have as its centrepiece a peacock, as a direct link to the famous peacock throne of the Mughal emperors. By February 1891, Ram Singh had already prepared some ‘brilliant

drawings’ and had shown them to Kipling. By April, work began in earnest to build the room of the Queen’s dreams. Here in the Durbar Room, she recreated the India that she could not visit. The ceilings and walls of the room were covered in ornate plaster carvings that resembled the architecture of both Mughal India and the Hindu temples of Rajasthan. The minstrel’s gallery was decorated with wooden

jali

(latticed) work completing the effect of a Rajasthani

haveli

or palace.

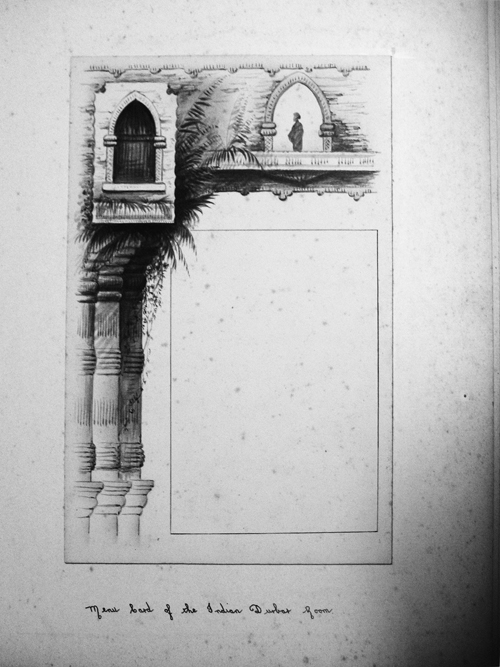

All the objects for the room, including the lamps, the light-fittings and chairs, were specially designed by Ram Singh and Lockwood. A large carpet from Agra covered the floor and the pottery was made from the Bombay Art School where Kipling had once taught. Even the curtain fabric was printed and embroidered in India. The room was completed by December that year and the Queen was so delighted with it that Ram Singh was invited to stay for five days over Christmas and given a signed photograph and a gold pencil case by the Queen as a Christmas present. The Durbar Room was now used by the Queen as a Banqueting Hall and she had the menu cards made with an Indian theme. With the ornate surroundings, the Indian attendants dressed in their turbans and the menu comprising the steaming hot curries that were always prepared in Osborne for luncheon, visitors would have had the complete oriental experience. The Queen enjoyed presenting this mini-India to visiting Indian Royalty. The Durbar Hall was always splendidly decorated at Christmas and the tableau vivant staged against the elaborate backdrop. Here, surrounded by her family and Indian servants, the elderly Queen lived out her Eastern fantasies.

In the kitchens at Osborne the Indian chefs were a small coterie working alongside, much to the amazement of, the European chefs. One of them, the young Gabriel Tschumi, who had recently arrived from Switzerland to join the Royal kitchens, was fascinated by the abundance of meat and vegetables in the Victorian kitchens as compared to the frugal diet in Europe at the time. Watching the Indian chefs at work left him in awe, and he recalled:

For religious reasons, they could not use the meat which came to the kitchens in the ordinary way, and so killed their own sheep and poultry for the curries [halal]. Nor would they use the curry powder in stock in the kitchens, though it was of the best imported kind, so part of the Household had to be given to them for their special use and there they worked Indian style, grinding their own curry powder between two large stones and preparing all their own flavouring and spices. Two Indian in their showy gold and blue uniforms worn at luncheon always served the curry to Queen Victoria and her guests.

9

Menu card at Osborne, which shows a sketch of a pillar with a turbaned man on the top right-hand side.

Interestingly, curry was always served at lunch, never for dinner, as was the practice with the British in India after the Mutiny. To serve curry for dinner would definitely not be

de rigeur

. French or English cuisine would be the requirement for these occasions. However, it remained a tradition in the last decade of Queen Victoria’s reign that curry would be cooked every day and served, regardless of whether or not her guests ate it. Her grandson, George, would later develop a taste for Madras prawn curry and insisted on always eating a curry with his meals.