Victoria in the Wings: (Georgian Series)

Read Victoria in the Wings: (Georgian Series) Online

Authors: Jean Plaidy

Contents

About the Book

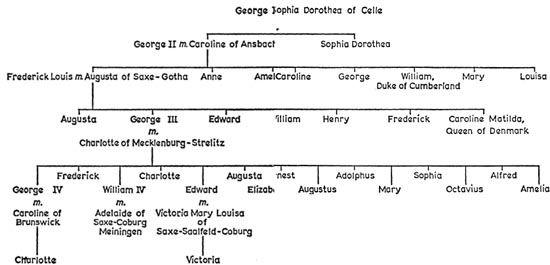

With King George III under lock and key suffering from perceived insanity and the Prince Regent in ill health, all eyes are on the Regent’s pregnant daughter. Unfortunately, the unthinkable happens and both Charlotte and her baby die in childbirth, leaving the age old problem of succession. For though King George III has many children, all are middle-aged and none have legitimate heirs to secure the Hanoverian dynasty.

The death of Charlotte causes a sudden enthusiasm for marriage among the sons of George III, as they compete to have children and secure their line of succession. William marries Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen while Edward marries Victoria Mary Louisa of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. Another son, Ernest, is already married and he too hopes to be the one to provide necessary children. King George dies, to be replaced by an ailing George IV, and Edward and Victoria succeed in having a daughter, also named Victoria. She waits patiently to become Queen, avoiding the plots, intrigue and danger that threaten to prevent her reaching maturity.

About the Author

Jean Plaidy, one of the preeminent authors of historical fiction for most of the twentieth century, is the pen name of the prolific English author Eleanor Hibbert, also known as Victoria Holt. Jean Plaidy’s novels had sold more than 14 million copies worldwide by the time of her death in 1993.

Also by Jean Plaidy

THE TUDOR SAGA

Uneasy Lies the Head

Katharine, the Virgin Widow

The Shadow of the Pomegranate

The King’s Secret Matter

Murder Most Royal

St Thomas’s Eve

The Sixth Wife

The Thistle and the Rose

Mary, Queen of France

Lord Robert

Royal Road to Fotheringay

The Captive Queen of Scots

The Spanish Bridegroom

THE CATHERINE DE MEDICI TRILOGY

Madame Serpent

The Italian Woman

Queen Jezebel

THE STUART SAGA

The Murder in the Tower

The Wandering Prince

A Health Unto His Majesty

Here Lies Our Sovereign Lord

The Three Crowns

The Haunted Sisters

The Queen’s Favourites

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION SERIES

Louis the Well-Beloved

The Road to Compiègne

Flaunting, Extravagant Queen

The Battle of the Queens

THE LUCREZIA BORGIA SERIES

Madonna of the Seven Hills

Light on Lucrezia

ISABELLA AND FERDINAND TRILOGY

Castile for Isabella

Spain for the Sovereigns

Daughters of Spain

THE GEORGIAN SAGA

The Princess of Celle

Queen in Waiting

Caroline, the Queen

The Prince and the Quakeress

The Third George

Perdita’s Prince

Sweet Lass of Richmond Hill

Indiscretions of the Queen

The Regent’s Daughter

Goddess of the Green Room

THE QUEEN VICTORIA SERIES

The Captive of Kensington

The Queen and Lord M

The Queen’s Husband

The Widow of Windsor

THE NORMAN TRILOGY

The Bastard King

The Lion of Justice

The Passionate Enemies

THE PLANTAGENET SAGA

The Plantagenet Prelude

The Revolt of the Eaglets

The Heart of the Lion

The Prince of Darkness

The Battle of the Queens

The Queen from Provence

The Hammer of the Scots

The Follies of the King

The Vow of the Heron

Passage to Pontefract

The Star of Lancaster

Epitaph for Three Women

Red Rose of Anjou

The Sun in Splendour

QUEEN OF ENGLAND SERIES

Myself, My Enemy

Queen of this Realm: The Story of Elizabeth I

Victoria, Victorious

The Lady in the Tower

The Goldsmith’s Wife

The Queen’s Secret

The Rose without a Thorn

OTHER TITLES

The Queen of Diamonds

Daughter of Satan

The Scarlet Cloak

Victoria in the Wings

The first book in the Victorian Saga

Jean Plaidy

for Mary Barron

The Momentous Year

IT HAD BEEN

a momentous year. Napoleon had been sent into exile, his power broken. No longer could mothers quieten their children with the threat ‘Boney will get you!’ because Boney was an ineffectual exile whose grandiose dreams had been shown to be nothing more than such, and the smallest child knew it. He was a figure of ridicule, hatred or pity – one could decide according to one’s nature; but all agreed that there was nothing to fear from him. He had been beaten at Waterloo by the invincible Wellington and the bewhiskered Blücher, and Boney’s days of glory were over.

‘Boney

was

a warrior, Jean François,’ sang the children derisively.

England had never been so rich nor so powerful. Led by the exquisite taste of the Prince Regent the arts flourished; rarely in the history of the country had so much encouragement been given to creative genius. Nowhere in the world – now that French glory had departed – was there a mansion to compare with Carlton House; the Pavilion at Brighton, that oriental extravaganza, was unique though it might owe its conception to Chinese artists.

So much splendour; so much glory. There was no other country in the world so powerful; yet there were people not far from Carlton House, in the hovels of Seven Dials, dying of starvation; the national debt was overwhelming; the weavers of Manchester were in revolt against the installation of machinery and the hungry crowds marched to London, burning hay-ricks as they came, ominously singing the Marseillaise. Never far from the minds of every member of the royal family was the memory of the terrible fate which had befallen their cousins across the Channel: bestial violence, murder, the collapse of a régime and resulting chaos, the most bloody revolution the world had yet known.

The Duke of Clarence had said in one of his fatuous speeches that the people of Europe had a habit of cutting off the heads of their kings and queens and soon there would be many thrones without kings and kings without heads.

Clarence was the fool of the family. He had not been educated as well as his brothers because his father, determined to make a man of him and remove him from his brothers’ demoralizing influence, had sent him to sea when he was thirteen; and although a tutor had accompanied him, the Duke having no inclination for learning and circumstances being understandably not conducive to study, he had become a better sailor than a scholar.

The Prince Regent was dissatisfied with life. He longed for the one thing he lacked; the approbation of his subjects; but no matter what he did he could not win this. They hated him; his faults were exaggerated; his virtues minimized. Prince Charming of his youth had become Prince Ridiculous of his middle age.

Driving to open Parliament on a bitter January day his carriage had been surrounded by a hostile mob who had broken the windows; and someone had taken advantage of the tumult to fire a shot which missed him by an alarmingly few inches.

The Regent was not as physically brave as his father who had faced similar acts of lese-majesty with calm. ‘There is One who disposes of all things and in Him I trust’, George III had commented when a would-be assassin had fired a shot at his carriage; and picking the bullet from his sleeve where it had lodged he had handed it to Lord Onslow, who was sitting with him, and remarked: ‘My Lord, keep this as a memorandum of the civilities we have received this day.’ The Prince Regent lacked his father’s faith; and the only part he failed to act with conviction was that of the man indifferent to death. He was worried about his health; he was not ready to die; and, being more cultured than his father, an unwashed, illiterate, unreasonable mob filled him with greater distaste.

What have I done to make them dislike me so? he asked himself. I have done everything I could to make this country great. I would have stood beside Wellington if it had been permitted; but as this was not to be I have honoured Wellington and made him my friend. I have brought beauty and culture to this country; I have even given them an heir to the throne, though what this cost me they will never understand. And yet they hate me.

His brother Frederick, Duke of York and

Commander-in-Chief of the Army, was not hated as he was, although he had given the royal family one of its biggest scandals when his mistress Mary Anne Clarke had been accused of selling commissions, and Frederick’s letters – banal, illspelt, revealing in the extreme – had been read in court. Frederick had necessarily been dismissed from his post in the Army, though he had regained it on his brother’s accession to the Regency. For a time Frederick had been the victim of lampoon writers and the cartoonists, but somehow he had crept back into a certain contemptuous favour.

Why can’t I do the same? wondered the Regent. He was cleverer than Frederick; he was the King in all but name; he had done his repulsive duty in marrying Caroline of Brunswick and had had a daughter by her. All this – and they showed no gratitude. They depicted him in their cartoons as twice the size he was; they wrote disgusting things about him; the writer Leigh Hunt had been fined and imprisoned for libelling him; they called him ‘fat’ – an adjective which made him shudder whenever he heard it; they exaggerated his extravagances; in fact they showed in a hundred ways that the most unpopular man in the kingdom was its ruler.

Often he remembered a long-ago conversation with Lord Malmesbury who had been his friend – although he would never forgive him for not warning him of the vulgarity of Caroline of Brunswick; for Malmesbury, as the King’s ambassador who had gone to Brunswick to make the arrangements for the marriage, had been fully aware of Caroline’s crudeness, her unsuitability and her lack of cleanliness. Whenever he thought of her his slightly retroussé nose which had been so charming in his youth twitched with disgust. If he could have married Maria Fitzherbert openly, all this would not have happened. He would have been a happy man, a monarch beloved of his people; and where could he have found a woman more worthy to be his queen than Maria?