Vietnam (22 page)

Authors: Nigel Cawthorne

In the election in November, Nixon beat Humphrey in a close vote. America now found it had a right-wing Republican president who had run on a peace ticket. This split the anti-war movement. But it soon became clear that, rather than ending the war, Nixon was expanding it and the peace lobby had to start up all over again. In September 1969 a former McCarthy campaign worker, Sam Brown, began the Vietnam Moratorium Committee with the intention of showing that anti-war protest was not confined to students. 15 October 1969 was declared National Moratorium Day and some 250,000 people from all walks of life took to the streets of Washington, DC to protest. Between 13 and 15 November another 500,000 demonstrated in response to the committee's call. By then the anti-war movement commanded popular support.

The Moratorium demonstrations had a great effect on the Pentagon defence analyst Daniel Ellsberg, one of thirty-six who had produced a massive report on the conduct of the war which became known as the 'Pentagon Papers'. Although the publication of the Pentagon Papers did not take place until in the 1970s, the report was written in the 1960s and had an effect behind the scenes. In June 1967, at the behest of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Ellsberg and his colleagues began reviewing America's policy in Vietnam, beginning in 1954. The resulting report took eight months to compile. Officially called 'The History of the Decision Making Process on Vietnam,' it ran to 47 volumes, 7,100 pages in all, cataloguing systematic government deception, cynicism, and incompetence in the handling of the war. Only 15 copies were printed. There were rumours that McNamara planned to leak the report to his friend Robert Kennedy to help him in his bid for the Presidency.

Ellsberg had been a keen supporter of McNamara and US involvement in Vietnam. But he was disillusion by what he learnt compiling the report. After the National Moratorium on 15 October 1969, he began secretly photocopying the study and passing pages to Senator William Fulbright, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and a prominent critic of the war. Later, he sent copies to

The New York Times

, who began publication on 13 June 1971. President Nixon slapped an injunction on the

Times

, but then the

Washington Post

began printing more extracts. When the

Post

in turn was silenced by an injunction, other newspapers in Chicago, Los Angeles, St. Louis and Boston took up the challenge. On 30 June the Supreme Court quashed the injunctions, condemning Nixon's attempt to gag the press. In the meantime, Ellsberg had given himself up to the police. He and another colleague, Anthony J. Russo, were indicted for theft but the charges were dropped in May 1973 when it was revealed that Nixon had authorised the burglary of the offices of Ellsberg's psychiatrist in an attempt to find evidence to smear him. The burglary was carried out by members of the White House staff in a sinister precursor to the Watergate break-in which would take place in 1972.

While they now commanded national support, some protests then began to take a more violent turn. The SDS had grown increasingly militant, and by 1969 it had split into several factions, the most notorious of which was the Weathermen, or Weather Underground, who began planting bombs. Over 5,000 bombs went off in all, including one that wrecked a bathroom in the Pentagon.

In 1970, protests against the incursion into Vietnam's neighbour Cambodia swept the universities. Conservative politicians demanded an end to campus unrest: California's Governor Ronald Reagan said, 'If it takes a bloodbath, then let's get it over with'.

His words came true on the campus of the traditionally politically apathetic Kent State University. When protests broke out there, the Governor of Ohio came to the campus and described the demonstrators as 'troublemakers' who were 'worse than the brown shirts' (Hitler's early followers in Nazi Germany) and the Communist elements, and also the night riders and the vigilantes. They are the worse type of people that we harbour in America'. He was standing in the primaries for the Republican senate nomination the following week.

The Ohio National Guard was called in. The protesters sang John Lennon's 'Give Peace a Chance' and the Riot Act was read. A campus policeman with a bullhorn ordered the crowd to disperse. They answered with cries of 'Pigs off campus' and 'Sieg Heil'. The National Guard commander, General Canterbury, ordered his men to load their rifles with live ammunition and don gas masks. From the top of a grassy knoll, 100 state troopers fired tear gas canisters into the crowd. The protesters hurled them back, along with rocks, lumps of concrete, and obscenities. Around 40 of the National Guardsmen moved down the hill to confront the crowd. A couple of times, they assumed firing positions to scare the demonstrators, but were eventually forced back. Then a single shot rang out, followed by a salvo from the troopers on the grassy knoll. Sixty-one shots were fired in all. No warning had been given.

The protesters had no idea that the troopers were armed with live ammunition. One demonstrator said that they were firing blanks, otherwise they would be shooting in the air or at the ground. But four students died. There was no indication that they were regular SDS activists. One of them, Sandra Lee Sheuer, was passing on the way to class. Jeffrey Miller was a registered Republican and William Schroeder was a member of the university's Reserve Officer's Training Corps. The fourth victim was Allison Krause. Ten more students lay wounded, one paralysed from the waist down by a bullet lodged in his spine. Ignoring cries for help from the crowd, the National Guardsmen shouldered their arms and marched away.

Attempts to justify the actions of the National Guard as self-defence were dented when the results of the FBI investigation into the shootings were leaked. The report concluded, 'The shootings were not necessary and not in order'. It also said, 'We have some reason to believe that the claim by the National Guard that their lives were endangered by the students was fabricated subsequent to the event'.

Even so, when the National Guardsmen were brought to trial they were found not guilty. However, eight-and-a-half years later the defendants issued a statement admitting responsibility for the shootings and expressing their regret, and in January 1979, the parents and students received $675,000 from the State of Ohio in an out-of-court settlement.

The shootings at Kent State brought the war home to white middle class America. The victims were not little yellow men on the other side of the world, or blacks in the ghetto, or student radicals from Berkeley. These were their sons and daughters, middle-class kids attending a relatively quiet campus in middle America. Over 150 colleges were closed or went on strike in the days following the killings. One hundred thousand protestors marched in Washington, DC, though construction workers broke up a demonstration on Wall Street while the NYPD looked on.

Although Nixon dismissed the protesters as bums, America was shocked. Even the Education Secretary Robert Finch condemned the rhetoric that had heated the climate which led to the Kent State slayings. The days when hippie protesters put flowers in the barrels of soldier's guns were gone. The Weathermen set up a National War Council. The ladies' room in the US Senate was blown up. The home of a judge trying African-American radicals was bombed, as was the New York Police Department. An attack on an army dance at Fort Dix was planned. More seriously one person was killed and three wounded by a bomb attack on the army's Mathematics Research Center in Wisconsin. But the outrage of middle America meant that mainstream politicians were now forced to tackle the issue. Nixon was forced to withdraw American troops from Cambodia and funding for the war was cut by Congress.

But protests continued. In May 1971, 12,000 demonstrators were arrested in Washington, DC. In November that year there were large-scale rallies in 16 cities. By then Nixon, the man who had come to power offering 'peace with honour', was the focus of the protests.

One of the most powerful propaganda weapons the anti-war movement had was the group Vietnam Veterans Against the War. These men could hardly be accused of being cowards or Communists, accusations regularly hurled at student protesters. They had served their country in Vietnam, and decided the war there was wrong. They turned up to demonstrations in uniform, though they often threw away their medals. The injured – amputees and men in wheelchairs – added a powerful wordless protest to student chanting. No New York hardhat was going to beat them up. They even defied a Supreme Court ban on demonstrating in Washington, DC, with impunity.

On 28 December, 1971, 16 Vietnam veterans occupied the Statue of Liberty, hung the Stars and Stripes upside down from the observation platform, and sent an open letter to President Nixon, saying, 'We can no longer tolerate the war in Southeast Asia regardless of the colour of its dead or the method of its implementation'.

In 1972, wheelchair-bound Vietnam Veteran Ron Kovic gatecrashed the Republican convention on the night of Nixon's speech accepting the presidential nomination, telling the guards who tried to throw him out, 'I'm a Vietnam veteran... I've got just as much right to be here as any of these delegates. I fought for that right and I was born on the Fourth of July'.

For two minutes, he condemned the war on national television. Kovic's story was later immortalised in Oliver Stone's controversial film

Born on the Fourth of July

.

Quite apart from all these anti-war demonstrations, opinion polls revealed disillusionment with the war throughout the nation, and it was clear that one way or the other the US had to extricate itself from what was graphically called the 'Vietnam quagmire'. Bowing to the inevitable, Nixon concluded a negotiated settlement to the Vietnam War, which was signed in Paris in January 1973.

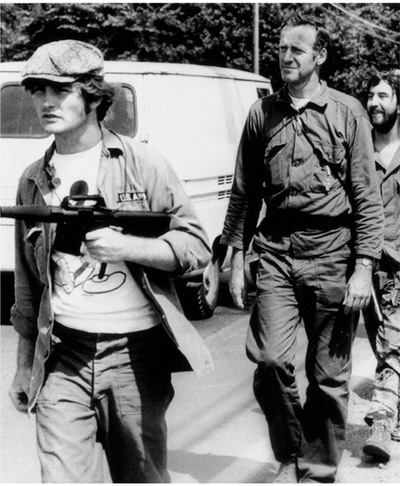

A member of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War group (VVAW) wields a plastic gun as the group march from New Jersey to Pennsylvannia, June 1970.

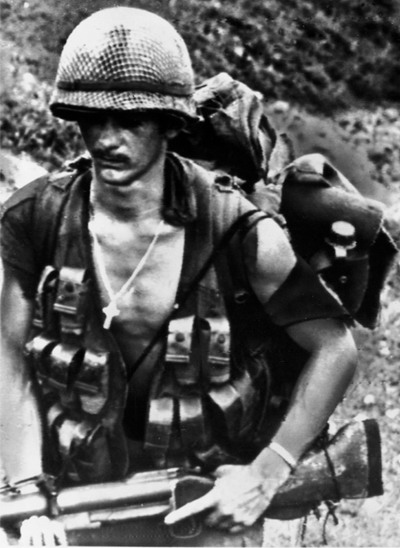

A soldier of 198th Light Infantry Brigade shows support for Moratorium Day by wearing a black armband, 15 October 1969.

THE COLLAPSE OF MORALE

THE WAR WAS NOT

universally popular even among the military. On 8 July 1965 a US captain was court-martialled in Okinawa for feigning mental illness while serving in Vietnam. On 11 June 1966, Private Adam R. Weber, an African-American soldier in the 25th Infantry Division, was sentenced to one year hard labour for refusing to carry a rifle because of his pacifist convictions. In September, three army privates were court-martialled for refusing to go to Vietnam. The court rejected the defence argument that the war was immoral and illegal. In March 1967, USAF Captain Dale E. Noyd sued in court to have himself reclassified as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam conflict. His petition was denied in June. In August, the US Court of Military Appeals upheld a sentence of one year hard labour on a soldier found guilty of demonstrating against the war.

To start with, these military objectors were few and far between. On the other hand, by September 1965, over 100 US servicemen were volunteering for service in Vietnam every day, although the enthusiasm for the war did not last long, even among the professional soldiers who longed for combat experience. The cherished discipline of the army and the Marine Corps was soon corrupted by exposure to the delights of Saigon and the other cities of the east.

Before the war Saigon had been known as the 'Paris of the Orient'. Like Paris, Saigon was famous for its prostitutes. During their occupation, the French had both legalised and profited from it, and had developed a system of military brothels. Mobile brothels followed the troops and at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 Vietnamese and North African prostitutes acted as nurses and even frontline fighters. The South Vietnamese army inherited the system but, under the Diem regime, the president's sister-in-law Madame Nhu, known for her tight dresses and expensive jewellery, tried unsuccessfully to clean up the city, banning all overt forms of licentious behaviour including the latest American dance craze, the Twist, condemned by many as lewd. Madame Nhu had people arrested for wearing 'cowboy clothes', and she and her husband, warlord Ngo Dinh Nhu, took out full-page newspaper ads denying their involvement in illegal activities; an attempt doomed to failure.