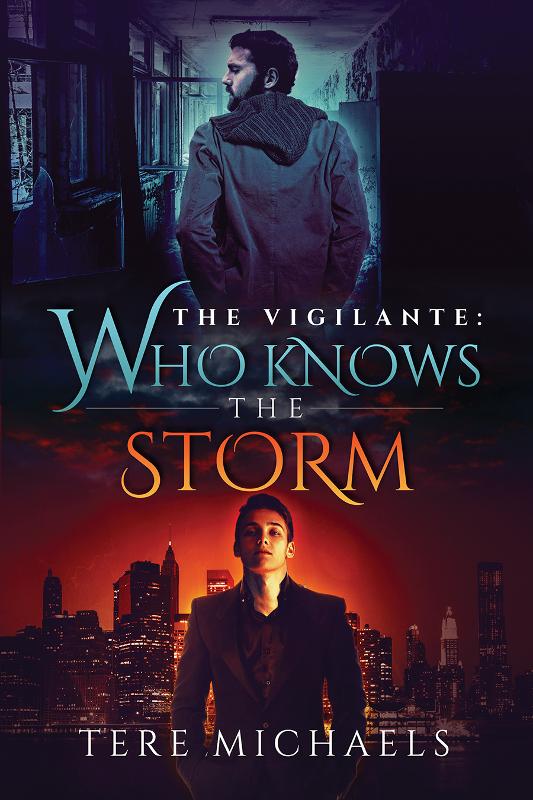

Vigilante 01 - Who Knows the Storm

Read Vigilante 01 - Who Knows the Storm Online

Authors: Tere Michaels

Someone I loved once gave me a box of darkness. It took me years to understand that this too was a gift.

—Unknown

You need chaos in your soul to give birth to a dancing star.

—Friedrich Nietzsche

Prologue

New York City

Before

S

EPTEMBER

N

OX

B

OYET

is fifteen and his only problems in the world are his upcoming physics test and the tiny shorts Patrick Mullens insists on wearing to lacrosse practice every damn day.

His father is traveling to parts unknown—again. He talks to the man’s assistant more than he talks to his father, by a ratio of about ten to one. His mother has been at the hospital for four months due to “exhaustion”—again. Exhaustion means relapse and hospital means sanitarium, and he stopped needing codes when he was ten. Mrs. Grimes from across the street checks in on him every day, brings leftovers from the family dinners, and Nox uses the emergency credit card to eat a lot of pizza.

Then it starts raining.

O

CTOBER

N

OX

B

OYET

is a few weeks away from turning sixteen. He desperately wants two things: for Patrick Mullens to stop being a cock tease (five minutes into a mutual hand job in the shower stall after practice and suddenly he remembered a piano lesson? Bullshit.) and for his father to let him have the old Beemer they leave at the house upstate.

He’s getting A’s in everything at Trinity, and the headmaster referred to him as a “fine young man, like your father” after assembly. He’d tell his parents this in another attempt to get the Beemer, but his father hasn’t been home in over a month. His mother? Five.

Mrs. Grimes said the LaMontes are leaving Manhattan because of the weather. She’s staying to “watch the house,” and Nox is secretly glad.

And it hasn’t stopped raining for almost three weeks.

N

OVEMBER

N

OX

B

OYET

is in hell.

Most of the neighborhood is deserted. Residents have fled for drier climes—some have moved temporarily to winter bungalows and summer residences outside the city. Every day there’s another solemn story of people drowning and residents of the city and outlying areas being rescued by boaters. The subways and trains aren’t running due to flooding. The tunnels in and out of the city are closed. Buildings have collapsed under the strain of the torrential downpours and ministorms sweeping in from the ocean. Nowhere on the island seems safe—and no one is making ark jokes anymore.

Mrs. Grimes has her nephew Roy staying with her at the house “for protection.” She still comes across the street, splashing through the muddy river that is Ninety-Second Street, to check on him. He wants to tell her it’s okay and he’s fine, but honestly—he’s not.

Trinity, like all the other schools in Manhattan, has cancelled classes. Most of his friends have left the city with their families. Patrick called him twenty minutes ago to say they’re going to stay with his grandmother in Chicago. There are rumors the bridges will be shut down, like the tunnels already have. He’s trying to be brave, but his father’s assistant says she can’t reach him and the lady who answers the phone at his mother’s hospital says she isn’t taking calls. She’s in “isolation.”

So is he.

He stays in his room, trying not to jump at every little sound. The power has been going on and off for almost two weeks, and if it weren’t for all the crazy survivalist stuff his mother has hoarded in the basement, things would be way worse. He’s never been so grateful for her paranoia and his father’s black AmEx

.

He’s only a kid and he’s not ready for this much responsibility.

O

N

HIS

sixteenth birthday, a policeman comes to the door as National Guardsmen roll down the street in jeeps, using a loudspeaker to tell people to be prepared to evacuate. He asks if Nox’s mother is home, or another adult, but no, Nox is alone.

Very alone.

The policeman tells him he’s very sorry, but Nox’s father is dead. His body was found at his office building near the stock exchange—a mugging, most likely. His assistant identified the body.

So sorry for his loss.

Nox doesn’t cry. He walks around the house in a fog, the loudspeaker announcements of urgency fading to background noise. His father is dead. His mother is lost in a land of her own.

There are no grandparents, no aunts or uncles. All of the people considered “family friends” have fled, and really, it was mostly social, the connection from the Boyets to the movers and shakers of old money on the Upper West Side. They were hidden away in this house, shamed by his mother’s illness and his father’s workaholic ways.

He has no one.

A

DAY

later, the National Guard goes door to door telling people they have to evacuate in twelve hours. The ferries will be departing from the Seventy-Ninth Street Boat Basin. Nox, curled up on his bed, looking at pictures of his mother on the wall, makes a decision.

He fills his waterproof backpack with some food and water and all the money he can find in the house. He layers on the ski clothes he got last Christmas and prints out a map that will direct him all the way up to Inwood, where his mother’s sanitarium, Morningside, is.

He’s going to get her, and then they’re getting the hell out of Manhattan.

H

E

HAD

no idea what he was walking into—and no idea he wasn’t coming back.

Now

S

OMETIMES

PATROL

took Nox down past what used to be the Seventy-Ninth Street Boat Basin on the West Side. There was a memorial to the people who died when the ferries sank on Evacuation Day—a block of stone engraved with 1,957 names, the date. “Unknowns” tacked on the bottom for those who were never identified brought the number well over 2000. No bother of sentiment, no solemn saying emblazoned on a bronze plaque.

Only two names on that list mattered—he knew the location by touch, knew the curve of each hammered-out vowel. They were the reason he couldn’t ever leave this place—they were the reason he walked fifty blocks a night to make sure the neighborhood was safe.

There were other memorials, other tributes to those who died during the storms. The floods downtown and on the Island, the fires in the Bronx and Queens, the building collapses on the East Side. But Mayor Freck’s legacy was an administration that liked to remind the survivors their loved ones would want them to move on—they would have wanted the city to rise again.

Plaques said,

We remember

. The enormous hotels and casinos that cluttered inhabitable parts of the island said,

We’ve moved on

.

T

HE

D

ISTRICT

—blocks and blocks of Central Park West, Times Square, and Midtown real estate converted into casinos and hotels, built up and beautifully maintained, with a thriving clientele of wealthy jet-setters and a well-staffed security force that kept it as calm and orderly as a debutante ball. The New City.

After the storms, the city was left a hollow shell. So many uninhabitable buildings, so many residents forced into shelters in New Jersey, Connecticut, even Pennsylvania. Wait for the water to recede, wait for inspectors to check the buildings, wait for insurance companies. Real estate prices went from millions to pennies as abandoned buildings continued to sit dark and empty, molding as months passed with no one to tend to the mess. People, museums, and businesses relocated, with vague talks of “going back” when things got fixed.

When the federal money was slow to trickle in, the “going back” became “moving away permanently.” With no commuters and no tourists, New York was a ghost town within five years of the evacuation. The wealthy business owners and their boards collected insurance checks and moved elsewhere—other states offered incentives to relocating businesses and the bottom line was simple. Cheaper to be elsewhere, cheaper than trying to rebuild. Cheaper to take tax breaks and move the headquarters of your company to Chicago or Dallas. Even better, most of your employees followed, because there wasn’t anything to tie them to a rapidly declining city.

The middle and lower classes just couldn’t survive. Many stayed as long as they could but in the end, six years after the storms, the population of New York dwindled to the lowest numbers since the turn of the century.

Three years later, as the remaining citizens complained of war-zone-like conditions and the rest of the country wondered why nothing was being done besides organized looting—Broadway in Las Vegas, museums around the world dividing up the great works of art, pro sports teams lured to nearby cities—a mayoral candidate named Louis Freck swept in like Hannibal on the elephant’s back.

He demanded more aid from the federal government while at the same time preaching the resiliency of New Yorkers. He called for a radical plan to save the city: bring money in by lining the streets with gold and hookers.

Oh, he put it in a much nicer way. Playgrounds for the rich and richer. There were dioramas and beautifully rendered sketches for presentations, followed by minimovies and simulations as Freck’s popularity grew. Worthless real estate revitalized by investment—all from the pockets of developers, not the citizens. The desperate New Yorkers attended rallies, cheering at the chance to have some hope. Rebuild the industry and the rest of the city would grow around it.

Freck won. No one even remembered who ran against him.

Things happened quickly after that. Dump trucks and backhoes from private companies cleared away the rubble; construction cranes once against dotted the streets. After two years, the skyline began to rise again.

Freck made an impassioned plea, and legalized gambling came to Manhattan Island.

Casinos.

Luxury hotels.

Boutiques.

Five-star restaurants.

The people in the outer neighborhoods waited for the trickle-down effect as time ticked by. One year, two years. Three years—so many promises, but the District needed time to grow, to make back their investments. It would happen—just be patient. Surely all of the money being poured into the District by visitors—surely it would reach their desperately empty pockets. Jobs would be plentiful.

Freck kept a few promises. He left some neighborhoods alone, zoned for residential rather than commercial use. They had power, fresh water. Crews removed debris from roadways, sometimes even repaved. A newly visible police force—as in, people actually saw black-and-whites cruising the streets.

It was a start, so no one questioned the curfew in the Old City. And now? Seventeen years since the Evacuation? No one bothered to complain about it. They’d grown used to the restrictions, the “doing without”—grown accustomed to the division of the city and abandoned their hopes that one day the largesse of the District would visit them as well.

Nox walked through Old Riverside Park, crossing up toward Ninety-First Street as he headed home. It was quiet. Curfew kept citizens inside after dark; the police didn’t bother to patrol this far north, and the dealers generally stayed downtown near the underground clubs.